By RACHEAL FEST

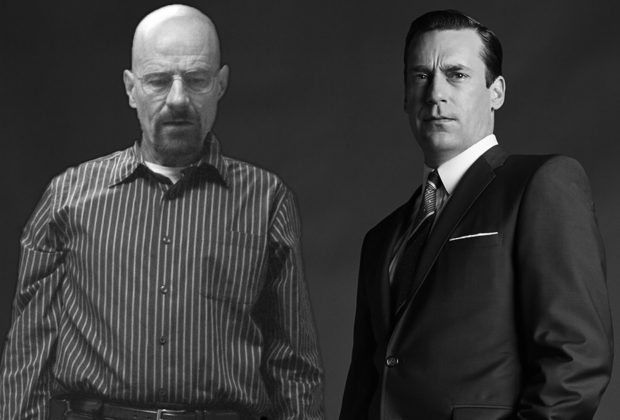

AMC launched the soon-to-be acclaimed serial dramas Mad Men (2007–2015) and Breaking Bad (2008–2013) against a backdrop of global economic collapse. As small-screen heroes Donald “Don” Draper (Jon Hamm) and Walter “Walt” White (Bryan Cranston) set out upon their very different journeys—the first destined for professional triumph at one of the world’s largest advertising firms, the second for death on the floor of a meth lab—the financial crisis of 2007–2008 inaugurated a severe recession and consolidated a new set of global realities. In its wake, economists explained, it was clear we had entered a “New Gilded Age,” a moment at which, in the US and elsewhere, rates of economic inequality had returned to late-nineteenth-century levels.[1]

As Americans lost homes, jobs, and pensions, US prestige television followed along divergent arcs of triumph and failure two protagonists of unusual imagination and intelligence. Matthew Weiner’s Don, born to a prostitute who dies in labor and then delivered over to an abusive father and stepmother, ascends out of the ashes of his depression-era childhood to become one of 1960s Madison Avenue’s most successful executives. Vince Gilligan’s Walt, a chemist who abandons entrepreneurial pursuits for a job as a high school chemistry teacher after he and his college girlfriend separate, finds himself in the series’ pilot financially unprepared to fight a cancer diagnosis, or to leave after his death resources that would help protect his wife and children from the economic difficulties he knows they will face without him. He builds over the course of five seasons an illicit (and corporate) drug empire, producing and distributing across the contemporary American Southwest, Mexico, and Europe high-grade methamphetamine hydrochloride (or “crystal meth”).

Don and Walt, critics have noticed, share the economically and socially embattled brand of white, heterosexual masculinity that “Golden Age” television has featured since HBO launched The Sopranos in 1999. But I want to consider here another unremarked set of commonalities that permits us to read them together as figures responsive to contemporary conditions.[2] Curiously, Weiner and Gilligan both name their protagonists for the nineteenth-century US poet Walt Whitman. And both dramas, as I will explain in a moment, require that Don and Walt conceal these affiliations from those they know and love. Mad Men and Breaking Bad thus invite us to read the adman and the meth kingpin as poets in the tradition of Walt Whitman, and they prompt us to consider why poets of this kind must deny that inheritance in order to achieve success in the twenty-first century. This common topos distinguishes Don and Walt from precursors such as Tony Soprano and locates the dramas they carry within a longer genealogy of texts preoccupied by the nature of poetic activity, broadly conceived as arts and culture, and its functions for modern life.

Reading Don and Walt as twenty-first-century Whitmans, I will argue, discloses a surprising set of resources Mad Men and Breaking Bad hold out to progressive and radical desires for democracy and equality in the New Gilded Age. These dramas proliferate visions of the poet that both complement and oppose ruling discourses—call them “neoliberal”—that perpetuate contemporary inequality in the US and beyond. Because both shows point the way toward alternative visions of poetic activity, however, I suggest they invite us to renew for the present imagination’s oppositional potential. Mad Men and Breaking Bad bid us reanimate the sense of historical self-consciousness left critics have argued poetic activity has concealed, rather than revealed, since the Second World War. They encourage us, first, to recognize how poetic human activity already shapes contemporary life, and second, to believe it might do so differently than champions of liberal capitalist democracy insist it must.

***

Born Dick Whitman, Weiner’s hero sheds the past that tethers him to a life of poverty and mistreatment when he goes to war in Korea. There, Whitman steals the dog tags, name, and identity of his commanding officer, Donald Francis Draper, after an explosion kills Draper. This gambit allows Whitman, now “Don,” to leave behind his cruel stepmother and become the self-made executive we encounter in Mad Men’s pilot. Over the course of the early seasons, Don goes to great lengths to hide his original identity from his wife and colleagues, and when the truth eventually comes out, the divorce Don fears follows. Gilligan’s Walter White shares Walt Whitman’s first name, nickname, and initials, a fact upon which the show’s volta depends. Walt successfully conceals his identity as a manufacturer and distributor of methamphetamine from his brother-in-law, FBI agent Hank Schrader, until Hank finds in Walt’s bathroom a copy of the 1855 Leaves of Grass a libertarian intellectual and known drug operative inscribed to Walt (“To my other favorite W.W.”). As Hank reads this inscription, he realizes the apparently gentle Walt has been the dark mastermind “Heisenberg” for whom he and the FBI have been searching all along. Walt appears in this moment as a triple figure. He doubles the quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg, for whom the present is too indeterminate to reliably predict the future, and the poet, Walt Whitman, for whom humans create the future out of an uncertain present.[3] When Hank discovers Walt’s affiliation with Whitman, this complex identity collapses.

What does it mean to read Don and Walt as poets in the tradition of Walt Whitman, and why must each conceal this inheritance in order to prosper in the twenty-first century? The preface Whitman composed for the first edition of Leaves of Grass (1855), a facsimile of which we see Walter White hold in his hands, gives one answer to the first question.[4] Whitman there elaborates for US traditions a version of the historical, creative, and imaginative understanding of arts and culture, broadly conceived, that emerged across the West’s language traditions in the nineteenth century.[5] Whitman describes his romantic vision of the poet’s nature and function this way: “folks expect of the poet to indicate more than the beauty and dignity which always attach to dumb real objects …. they expect him to indicate the path between reality and their souls.”[6] The “greatest poet,” Whitman writes, “brings the spirit of any or all events and passions and scenes and persons some more and some less to bear on your individual character as you hear or read,”[7] and in so doing, he or she “forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is.”[8] Poets, in other words, do not attempt to reproduce or represent existing reality, as a philosophical tradition with roots in Plato holds they do (poorly). According to Whitman, poets rather help “form” or shape out of existing conditions and materials “what is to be.” They persuade collectives to understand what “reality” has to do with them, thereby creating ways of thinking, seeing, and being that change over time.

Importantly, this creative, historical work is imaginative, rather than strictly rational. That is, poets as romantic traditions conceive them do not send us along paths to reality that can be tracked by reason or intelligence alone, although Whitman explicitly celebrates science, engineering, and other rational activities he does not oppose to poetry. They exercise the human faculty Samuel Taylor Coleridge calls “imagination” in order to invent, as Whitman does in his book, pleasing, sensuous forms, and these move us by appealing to our senses and stirring our emotions. Whitman is, most famously, a formal innovator, casting off received poetic conventions in favor of free verse, and innovation is important to him precisely because he believes novel poetic forms will help produce new forms of life. “Poetry,” from this perspective, names verse and art, but it also designates more broadly the ways humans rely upon sensuous materials, imaginatively worked over, to organize time, space, ourselves, and more. Whitman, in tandem with his contemporaries, develops a distinctive way of understanding and describing how humans exercise imagination to purposefully arrange language, images, and other materials in order to stir and influence collectives with the future in mind.

Leaves of Grass announces activity of this kind will no doubt serve in modernity the great democratic projects for “equality” and “political liberty” Whitman roots in the US experiment. This is in part because, as Whitman notes elsewhere, increased literacy rates in the nineteenth century enable poets for the first time to address a mass, rather than an elite, audience.[9] The new “paths” Whitman imagines his work will indicate between “folks” and “reality,” the preface makes clear, will be democracy’s paths; Whitman hopes the formal experiments his preface introduces will instantiate equality and enfranchisement. If the modern poet knows he participates in creating the future out of his affecting forms, Whitman models a progressive attempt to do so with the needs and interests of the great diversity of “common people” the US state promises to emancipate in mind.[10]

Prestige television’s twenty-first-century Whitmans, Don and Walt, both join and break with this tradition. On one hand, both pursue projects we might understand as poetic in the broad sense of the term that Whitman endorses; they exercise imagination to create out of their materials (words, images, molecules, compounds) novel forms, and these then create historically specific, and generally influential, experiences of meaning and value for those who encounter them. Both know they address multitudes. Don, the adman, is a master of words and images; his original forms stir desire and emotion in order to sell soft drinks, floor wax, and hotel stays. Walt, a formal innovator of a different kind, develops Blue Sky, his signature methamphetamine, by substituting methylamine for pseudoephedrine in his formula. His chemistry expertise enables him to synthesize a product purer and more potent than any on the market, so users seek it out for the intense pleasures it confers.

Both Don and Walt invent rousing original forms others admire and covet, and the dramas they carry capture attention, most fundamentally because Weiner and Gilligan permit us to watch their imaginations at work. Mad Men’s most exciting, acclaimed, and anticipated moments—scenes in which Don and others at his agency pitch new campaigns to corporate clients—invite us to enjoy advertisements and to meditate, with their makers, upon advertising’s nature and function. Breaking Bad inspires us to admire how Walt relies upon his forbidding ingenuity, formed and sharpened inside privileged educational institutions, to solve increasingly illicit problems—how to perfect a chemical procedure; how to evade the FBI; how to construct an international drug empire.

And yet, Don and Walt do not understand the nature and function of their poetic pursuits as Whitman did his. Neither believes, as Whitman does, his activity is creative and historical, and neither imagines his forms therefore produce with intention collective life. On the contrary, our twenty-first-century Whitmans explicitly deny their activities influence others, even as each becomes an increasingly prominent agent able to touch, organize, and alter masses. Don, for instance, says several times over the course of Mad Men’s run that he does not fabricate US culture. When a pot-smoking hippie in a downtown loft calls Don “the man” and accuses him of “manufactur[ing] want”—as if abbreviating John Kenneth Galbraith’s well-known critique of market design in The Affluent Society (1958)—Don dismisses him, echoing (or anticipating?) Margaret Thatcher. “The universe is indifferent,” Don says. “There is no system.”[11] In a later episode, Don tells a young woman who “just want[s] to know who’s in charge” in contemporary US life: “You’re in charge! I work in advertising.”[12] Walter White similarly refuses, for most of Breaking Bad’s run, to admit he has become a commanding economic driver and designer in the Southwest, reshaping and extending its drug economy by winning a devoted and growing following of users and distributors to his incomparably clean product.

Don and Walt instead share a common understanding of their poetic pursuits, different as these are. Both believe they exercise imagination and intelligence in order to satisfy, however they can, what they perceive to be their own and others’ deep and unchanging human needs. Don understands himself to be an intuitive expert who knows what others already want, and he believes he deploys his poetry to show them how to get it, along the way accumulating generous profits for himself and the corporations he serves. Walt believes his poetry enables him to protect his family and defeat his competitors, as might any weapon a man takes up on the dreamy savannahs of a fictional deep past (or the present’s bleak deserts).

Mad Men develops Don’s conception of his poetic activity during the presentations (or pitches) that punctuate each season. Don is a successful creative director and adman, the pilot quickly establishes, because he works upon reluctant corporate clients what he calls his “magic.” We get our first glimpse of that magic when he sells Lucky Strike’s board on a campaign that abandons state-proscribed health claims and hypes flavor instead. There is a method, it turns out, to this magic. When Don works it on clients, he brings them to understand, first, that their products already satisfy timeless and fundamental human desires (for sex, love, belonging, recognition, and more), and second, that the ad campaigns Don recommends will make a product’s innate function apparent to consumers. Don does not think about himself as a creator of meaning, value, or desire. He believes himself to be a revealer of existing truths, the assumption being apparently that his superior intuition grants him special access to them.

Don’s pitch to British car manufacturer Jaguar, delivered in season five, exemplifies this vision of the poet. Don stands against dark walnut in one of the opulent Manhattan interiors for which the show is known and describes to the luxury brand’s agents, a panel of white men in rich corporate uniform, their vehicle’s appeal. “[W]hen deep beauty is encountered,” Don explains, gesturing toward a mockup of a sleek, curvaceous, red coupe, “it arouses deep emotions, because it creates a desire, because it is, by nature, unattainable.”[13] This awkward sentence might fall apart when we read it on the page—too many causal conjunctions link too many commonplaces. But when Don utters it on screen, his sonorous voice intoning the profound syllables, it rings as would truth ancient and absolute. “We’re taught to think that function is all that matters,” he goes on, “but we have a natural longing for this other thing.” Straight, white men want luxury vehicles, Don tells his audience, for the same reason, and in the same way, they want beautiful women. Don’s activity, advertising, does not generate this longing. It is as natural, essential, even biological, as any sexual aspiration, and Don’s poetry simply discloses this to manufacturer and consumer alike.

To shore up Don’s “magic,” which in a single move renders the car market a playground for man’s reproductive will and disguises this sleight of hand as pure biological reality, Weiner exercises his own. As Don holds forth upon desire’s ultimate mysteries, the camera cuts away to another lavish room, an uptown suite, furnished in gilt and brocade. There, Herb Rennet, a member of Jaguar’s board, rendezvous with (curvaceous, redheaded) Joan Harris (Christina Hendricks), office manager at Sterling Cooper Draper Price (SCDP). (Don has since the pilot made partner.) Against Don’s wishes, the other partners at SCDP have asked Joan to spend the night with Herb, at Herb’s request, so that SCDP may win the Jaguar account; in return, SCDP has granted Joan a voting partnership.

As the camera cuts back and forth between tryst and pitch, Don in effect narrates both, heightening his presentation’s salacious timbre and intensifying the urgency of the ethical questions his words elicit. “I thought about a man of some means reading Playboy or Esquire,” Don says, “and flipping past the flesh to the shiny painted curves of this car. There was no effort to stop his eye. The difference is he can have a Jaguar.”[14] An assistant flips a square of poster board so Don can finally read SCDP’s proposed tagline: “Jaguar. At Last, Something Beautiful You Can Truly Own.” Splicing together Don’s and Joan’s performances in this way at once undercuts the distinction Don is making—in Mad Men’s universe, it turns out a man can “truly own” both a beautiful woman and her automotive counterpart—and completes the erotic equivalence. The scene renders sexual desire, that abiding force that joins us, destroys us, and (sometimes) ensures that our species will endure, identical with the will to acquire a luxury vehicle. Biology itself, Don assures his audience, obliges a man to covet a Jaguar, and the board should select SCDP’s campaign because it best exposes this fact.

If a kind of market Freudianism explains how and why Don’s poetry works on Mad Men,[15] a show preoccupied with eros, a different set of desires—perhaps they are thymotic[16]—motivates Walt’s poetry on Breaking Bad. (Don’s sin is lust; Walt’s deadlier sin, pride.) Gilligan establishes in the first episode that Walter White acts as he does in order to protect and provide for his family, a desire the series roots in the brand of gritty, post-municipal evolutionary survivalism it sanctions. The mainstream tradition of white masculinity Walt updates treats as innate the ambition to protect at all costs, and to the exclusion of all other lives, a core group joined by blood and love. By grounding Walt’s entrepreneurial world-building in the apparently incontrovertible facts of biotic actuality, the show explains, excuses, and at first, ennobles, the violence Walt enacts along the way.

Walt’s unwavering devotion to his wife and children, a constant refrain he voices until the series’ finale, encourages viewers to forgive him, long after we should hold him accountable, for producing and distributing a deadly substance and then killing—and not only the enemies he rapidly acquires as he does so. (Gilligan has explained in interviews he wanted to see how far this trick could carry his protagonist into our hearts—how long, he wondered, would viewers cheer on a hero as he transformed himself into a villain?[17]) Walt’s rare imagination, the show suggests, helps him and his kin survive our new American state of nature. Unprotected by a government that will expend capital to prosecute Walt’s crimes but will not to care for his dying body or support his disabled son after Walt’s death, excluded from partnership in the tech firm venture that capitalism and his own research helped his college friends transform into a fortune, and able to amass needed capital only via the crime boss and fast-food magnate Gustavo Fring (Giancarlo Esposito), Walt’s anti-imaginative acts of poetic making at once ensure his line survives and allow him access to the capital he comes to believe can redeem the early failures that wounded his pride.

Because these visions of poetic activity deny poetry’s creative function and imagine instead that biological or evolutionary truths at once motivate and are uniquely accessible to poets, they resonate with the popular ways of thinking about human life ruling economic and political discourses endorse in the twenty-first century. Radical critics of arts and culture in the US have since the 2007–2008 crisis come to rely increasingly upon the term “neoliberalism” to describe these discourses and the policies they license. This is in part because, as historian of economics Philip Mirowski demonstrates in his postmortem, Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste (2013), this abstraction seems uniquely able to name both the economic, political, and social systems that engender inequality now and the ideological, epistemological, and ontological assumptions that legitimate them.

Mirowksi’s book adds to the accounts of “neoliberalism” offered by theorists David Harvey and Wendy Brown a useful epistemological reading of the forces that rule the present. For Mirowski, we best understand the left epithet “neoliberal” as describing not only the transformations that have over the course of the twentieth century undercut democracy, economized politics, and aggressively liberated markets across the globe, but also as an “ideology of no ideology.” Fundamental to this worldview, Mirowski demonstrates, is the popular conviction that something called “the market,” a transcendental “information processer” and arbiter of truths, organizes human life better than can any brand of intelligent or purposeful human activity.[18] The market—a collective united by need and desire—emerges according to this view spontaneously and without intentional human intervention, so neoliberals argue it is uniquely able to organize involuntarily a wide range of human activities and to preserve human freedom in the process. This view at once affirms as liberatory the collective forms markets generate and denies that humans decisively help generate them.

Strategic denials of this kind recast as simultaneously naïve and totalizing the conviction that has since the nineteenth century defined the left’s projects for democracy—that purposeful human activity, collectively assumed, might help improve the conditions most people endure. Mirowski demonstrates that neoliberal paradigms, especially those for which Nobel Prize-winning Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek is a central figure, insist upon the limitations of rational and epistemological human pursuits and instead invest an irreducible human “ignorance” with transcendental power. Hayek argues humans can never know enough about ourselves, our world, and our desires to design a functioning economy that serves the needs of many. He believes we can only produce evolutionarily superior societies, such as the liberal capitalist democracies of the West, if individuals unthinkingly pursue independent and unexamined interests.[19]

Don and Walt both obscure from others their Whitmanian inheritance in order to guarantee success in the twenty-first century, and Mirowski’s vision of neoliberalism suggests one set of reasons why. Because Mad Men and Breaking Bad represent contemporary poets as self-interested diviners and appeasers of fixed human needs, rather than as creators of shared, historically particular desires, interests, and attitudes, their visions of poetic activity duplicate in the domain of imagination the same tactical concealment Mirowski believes economic discourses effect in the domain of reason and intelligence. These visions deny that purposeful imaginative activity helps fabricate things-as-they-are; they legitimize as inevitable existing conditions, obscure the forces that produce them, and conceal the creative capabilities that might transform them. Don and Walt cannot admit they are Whitman’s twenty-first-century inheritors, powerful figures who knowingly influence others to serve identifiable interests, because if they did, others might ask why contemporary poets do not help create better systems.

Students of twentieth-century radical criticism will recognize that Don and Walt, read this way, bring up to date a familiar story. Nineteenth-century poets imagined that their activities served the projects for democracy the bourgeois revolutions of the eighteenth century had set in motion. By the end of the Second World War, an influential line of twentieth-century criticism argues, imaginative activity had come to frustrate, rather than help realize, the transformed projects for radical or socialist democracy the left believed might redress liberal capitalist democracy’s otherwise ineradicable inequalities. Cultural or poetic objects of mass and elite appeal, critics such as Raymond Williams and Fredric Jameson have argued, helped perpetuate in the twentieth century an increasingly complex system of illusory satisfactions, thereby concealing the historical self-consciousness which might otherwise inspire collective work toward radical democracy.

Williams’ essay “Advertising: The Magic System” (1960) offers one of the definitive accounts of how consumer culture, the major site for poetic activity in the West after the late nineteenth century, betrays the egalitarian ambitions that might otherwise renew democratic projects. Williams argues that advertising is crucial to “the new ‘monopoly’ (corporate) capitalism”[20] that emerges in the West’s market democracies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries because it helps elites “control nominally free men.”[21] It does so by extending to those it imagines as “consumers” a system of satisfactions as magical as any other transcendental scheme. Advertisements promise people the products and services they consume will meet the complex range of human needs a society organized by corporate capitalism in fact cannot (and does not aim to) satisfy.[22] In a society that cannot finally “provide meanings and values” for most people, Williams claims, the promise of consumer choice furnishes customers “the illusion that they are shaping their own lives,”[23] and in so doing, it helps to forestall the “development of genuine democracy, in which the human needs of all the people in the society are taken as the central purpose of all social activity.”[24] For Williams, this system uses “certain skills and knowledge, created by real art and science, against the public for commercial advantage.”[25] It adopts the potent, sensuous techniques poets such as Whitman believed could help animate democratic forms of life and turns them instead toward projects for market control.

As discourses celebrating consumer culture obscured its creative influence in order to justify the economic system it bolstered, high culture’s forms abandoned claims about art’s power for different reasons, retiring the bombastic and triumphant language romantics such as Whitman invented to describe their activity. If Whitman and his contemporaries abroad first recognized their work helped “create” reality, and therefore affirmed and celebrated its liberating potential, their successors—the writers and artists we associate with “modernism” and “postmodernism”—became increasingly suspicious of these celebrations, not least because the First and Second World Wars seemed to many to demonstrate that creative activity of this sort yielded, not progress or democracy, but rather mass destruction and pervasive inequality. Since the early twentieth century, artists and poets have seldom claimed for themselves the enormous and optimistic imaginative abilities Whitman described. Preoccupied by art’s failures, aware of its irreducible complicity with violence, attuned to the dangers essential to imposing a vision on others, and aware that history and language already influence and over-determine the freedom any “self” or subject that points a path to reality might exercise, artists came to articulate their activity’s profound limitations as often as its capabilities.

With a version of this history in mind, Jameson, in his period-defining book on postmodernism, extended a version of Williams’ critique to all US arts and culture, including in his famous indictment both cultural forms proper to what Theodor Adorno called “the culture industry” and the elite aesthetic forms we still understand to be “artworks,” if only because they do not explicitly recommend commodities or attempt to generate wealth by appealing to multitudes. As post-industrial capitalism spreads and changes over the course of the Cold War, Jameson argues, “the history of aesthetic styles displaces ‘real’ history.”[26] If an emergent merchant class attained by the eighteenth century a sense of “historicity,” or historical self-consciousness, and enacted out of it the French and American bourgeois revolutions, Jameson argues postmodern cultural forms do not encourage, as early historical novels did, a “perception of the present as history.” After WWII, a surface-drama of images, to which even left artists contribute, substitutes for revolution empty formal change, calling into question the notion that changing sensuous forms can help promote broader changes in collective life. Postmodern artworks, Jameson argues, do not help people understand their actual political and economic positions within a perplexing technological and global system of organization, and they do not help them imagine how they might institute through purposeful activity democratic socialism.

As latecomers to this long story about imagination’s failures, Don and Walt confirm the obvious: in the new millennium, radical democracy’s messiah poets still have not come to deliver the goods for the left. These twenty-first-century Whitmans remind us that bad poets of all stripes continue to produce, as they did last century, magical systems as empty and destructive as they are dazzling and marvelous. Don and Walt still do not and cannot satisfy the range of deep human needs they promise commodities will meet, and worse, they do not pretend to try. They are content to deploy their enormous share of imagination and intelligence for self-interested and ultimately elite ends. Don is a conjuror under his own spell, a wicked Whitman who creates a deceitful world in which even he, its architect, cannot find happiness. Mad Men takes us behind the scenes at his magic show, but it does not expose how his tricks succeed.

Walter White, an even more unscrupulous poet, produces methamphetamine, substrate of a second brand of dangerous magic. When users ingest substances such as Walt crafts, concentrated (and, at first, easy to attain) affects animate them—intense pleasure, total confidence, burgeoning genius. So satisfying are these experiences that those who succumb to addiction aim only to secure and ingest the substance they prefer. The substance’s physiological and psychotropic effects ensure it alone comes to confer upon habitual users meaning and value, so obtaining it becomes the only meaning-making task worth pursuing. Walt, a chemist who explicitly teaches his disciples “cooking meth” is a precise science, and not an “art,” is thus a new kind of poet for an ancillary magic system—the drug economy—which late capitalism has had to evolve in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries to supplement consumerism.[27] This system requires of its poets and their acolytes no imaginative labor at all, as Breaking Bad ‘s meth binges expose.[28]

Don and Walt thus bring up to date poetry’s catalogue of established betrayals. They reveal how imagination generates ruling systems of meaning and value, insists they are real, and then erases itself, obliterating along the way any evolving sense of historical self-consciousness that might prompt purposeful change. Must we therefore accept earlier democratic visions of poetry’s potential are hopelessly dated, tied to a compromised project for parity and liberty that now contributes to inequality? Might poetic or imaginative activity, conceived another way, help restore a transformed sense of historicity?

Although Mad Men and Breaking Bad are by no measure radical works, I want to suggest in conclusion that renewed creative and historical visions of poetic activity haunt the neoliberal views of the poet each proliferates. In both series, Don and Walt come to recognize they exercise generative powers that shape forms of life through sensuous formal innovation. Mad Men and Breaking Bad first reveal Don and Walt as creative figures of this kind in limited, comfortable ways when the series expose their protagonists’ hidden identities.[29] When those closest to Don and Walt discover their affiliations with Whitman, their friends, families, and enemies learn Don and Walt have each treated themselves as poetry, erasing their pasts and inventing new identities. Don and Walt are new versions of the self-made men American traditions celebrate—we might call them poets of the self. Contemporary neoliberal discourses, as Mirowski’s account of them suggests, sanction this mode of autopoiesis. Today, the “self” is perhaps the only site of poetic making dominant ideologies acknowledge; it is a site at which poetry’s creative function can be safely affirmed because self-making does not aim to transform external conditions. As figures who transform themselves in order to meet the needs of the market, both as producers and consumers, Don and Walt represent the fragmented, unstable, entrepreneurial subject of the present.

These poets also come to realize their activities have broader collective effects, however. At different moments, each considers, and thereby invites audiences to consider, not only how they have transformed themselves, but also how they have transformed others. Both Don and Walt come to question the biologically rooted interpretations of their activity’s nature and function to which they at first subscribe, and each also begins to articulate instead an alternate vision. These visions are spectral, unformed. They haunt the conclusions of these dramas, just pointing the way toward radical conceptions of poetry and imagination that might understand first, that humans help create the world, and second, that we do so in limited, strictly material ways, as romantic conceptions of imagination did not recognize. These spectral dreams permit us to read Don and Walt as early figures for revitalizing historicity and its democratic impulses.

Mad Men’s finale catches up with a single, rootless Don as he settles into a New Age retreat at Big Sur (modeled on the Esalen Institute). Having fled New York for the other coast after his agency merged with the enormous (nonfictional) firm McCann Erickson, Don has been out on Jack Kerouac’s open road for several episodes. In California, he goes to therapy at last, reconciling his past traumas as he listens to a neglected, cardigan-clad everyman confess loneliness. In the show’s final shot, a redeemed Don meditates on a sunny hillside. We see him smile, and then the camera cuts away to show us one of advertising history’s most celebrated imaginative achievements, McCann Erickson’s 1971 “Hilltop” spot for Coca-Cola. A crush of fresh, diverse young faces, crowded in the grassy sun, join in saccharine chorus: “I’d like to teach the world to sing / In perfect harmony / I’d like to buy the world a Coke / And keep it company—That’s the real thing.”[30] We assume in this moment Don recovers his will to work and returns to New York to create this iconic ad for his firm. As a poet, Don resembles in conclusion the Whitman of “A Passage to India.” At the lip of the continent, at the end of the open road, Don shoulders his duds and looks to the East, projecting across the rest of the globe America’s imperial, corporate songs. This ending consolidates our vision of Don as a poet of the magic system, and it signals the giant imaginations he represents have harmonized the world around commodities market economies promise will bring goodwill and multicultural unity to all comers.

Along the way, however, Don sometimes questions the understanding of his activity that supports this imperial dream. In season four, for instance, Don argues with SCDP consultant and psychologist Dr. Faye Miller (Cara Buono) over the strategy the agency should develop for Ponds Cold Cream. Their argument is at its heart a dispute about what advertising is and does. Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss), the young copywriter Don mentors over the course of the show, has suggested SCDP promote Ponds as part of a pleasurable regime of self-care for women. After Dr. Miller holds a focus group with young, single women in the office to test this strategy, she tells Don her research “rejected” Peggy’s “hypothesis.”[31] “I’d recommend a strategy that links Ponds Cold Cream to matrimony. ‘A veiled promise,’” Dr. Miller says. Don dismisses this counsel—“Hello 1925,” he says, sarcastically. “I’m not going to do that. So, what are we going to tell the client?” Dr. Miller bristles. “I can’t change the truth,” she tells him. Provoked, Don asks, “How do you know that’s the truth? A new idea is something they don’t know yet, so of course it’s not going to come up as an option. Put my campaign on TV for a year; then hold your group again. Maybe it’ll show up.” He goes on: “you can’t tell how people are going to behave based on how they have behaved.”

In this moment, Don recognizes his poetry—words, images, narratives—influences the way collectives think, feel, and act. Although Don most often insists, as he does in his pitch to Jaguar, that advertisements tap into existing desires, when Faye voices this view, Don resists it. He challenges her claim that what people say they want at any given moment should be treated as a fixed and unchanging reality. Don seems, just for a moment, to understand that his activity influences desire in ways that change over time. It does not appeal to innate longings; it actually helps fashion them, and it does so with explicit interests—here, transforming conservative gender roles—in mind.

While Don acknowledges that his imagination influences collectives now and again over the course of Mad Men, Breaking Bad builds to Walter White’s poetic self-recognition over five seasons. In the series’ penultimate episode,[32] Walt at last admits to himself what his family and associates (as well as viewers) have known since Walt murdered Fring, his boss, at the end of season four, and then usurped his meth empire.[33] Before this event, Breaking Bad skillfully set for Walt, and for viewers, a series of traps designed to distance him from his own rational, ethical, and imaginative agency. The first seasons place Walt in an escalating series of kill-or-be-killed scenarios—the first is probably the most memorable, if only because Walt and his accomplice, Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul), gruesomely dissolve in acid the dead bodies of the drug dealers they had to slay in self-defense[34]—each of which prompts Walt to violence for inevitable, necessary, and pseudo-evolutionary reasons. (Walt’s façade of helplessness, of course, begins to deteriorate as early as season two, when he stands by and watches Jesse’s sleeping girlfriend die of a heroin overdose because she has tried to blackmail Walt.[35])

In the series’ penultimate episode, Walt, who has colluded in a series of events that led to his brother-in-law Hank’s death, has fled the Southwest to live free or die off the grid in New Hampshire’s snowy mountains. Walt knows he has left his wife, son, and newborn daughter poorer than ever. He cannot share with them the money the state knows he earned illegally, and the state’s search for him now implicates his wife. Walt calls his son at school and begs him to accept some of Walt’s remaining money—Walt says he can send it to a friend. Ragged from illness, rasping into a bar’s payphone, Walt begs his son to accept a hundred thousand dollars: “The things that they’re saying about me, I did wrong, I made some terrible mistakes, but the reasons were always—things happened that I never intended— […] I wanted to give you so much more, but this is all I could do, do you understand? Son, can you hear me? Do you understand?” Enraged, Walt’s son rejects this offer and rebuffs Walt’s attempt to distance himself from his own actions and their consequences. “You killed uncle Hank. You killed him,” he says, emphasizing again and again Walt’s culpability. “You asshole! You killed uncle Hank. Just shut up. Just stop it. Stop it. I don’t want anything from you. I don’t give a shit. You killed uncle Hank. You killed him.” Although Walt pleads with him—“Your mother needs this money. It can’t all be for nothing”—his son will not accept it. “Just leave us alone,” he says. “You asshole. Why are you still alive? Why don’t you just, just die already? Just die.” These words crush Walt. His face collapses and he struggles to stand.

When his son hangs up on him, Walt calls the DEA’s district office in Albuquerque, turns himself in, and then moves to the bar to wait for local agents to apprehend him. As he sips his scotch, however, he sees his ex-business partner and ex-girlfriend, the married couple Gretchen and Eliot Schwartz, talking about him on Charlie Rose. When asked if they hope to distance themselves from their one-time partner, Walt, now known nationally as the meth kingpin “Heisenberg,” Gretchen and Eliot downplay Walt’s contributions to their company, Gray Matter. Walt, viewers know, developed the technology that made Eliot and Gretchen wealthy, and his face hardens as they explain the man they knew as Walter White is gone. The episode ends, and when the finale begins, we learn Walt has decided to evade the authorities he tipped off so he can return to New Mexico and redeem his failures.

This concluding sequence sets up a finale in which Walt at last admits he has acted purposefully, with imagination and intelligence, to invent and disseminate a formally innovative product with wide-reaching consequences. As his son underscores Walt’s violence, Walt cannot deny any longer he has joined, and become an originator within, a brutal economic underworld. The mode of self-understanding Walt has cultivated throughout the entire series collapses. He cannot now tell himself his biologically determinate love for and devotion to his family explains or redeems his activities. Faced with this crisis of self-recognition, Walt’s first impulse is to relinquish his freedom and face the law. Hearing Eliot and Gretchen at once dismiss his contributions to Gray Matter and proclaim him figuratively dead, however, ignites his pride and prompts him to inhabit, now fully conscious of it, his creative role.

Walter White’s thymotic poetry proves to be even more destructive than does Don Draper’s erotic poetics. (Whitman’s modernist inheritors, most notably William Carlos Williams, emphasized the imagination’s capacity to destroy, a capacity indissoluble from its fecundity.[36]) In Breaking Bad’s finale, Walt for the first time exercises with resolve and impunity this tandem power to make and obliterate.[37] He does not tell himself he acts out of self-defense. Finally free to exercise unchecked his will, he launches a revenge plot at once brilliant and methodical. Walt returns home to Albuquerque, forces Gretchen and Eliot to set up a secret trust for his son, and then executes the white supremacist gang that stole money from him, slaughtered Hank, and reproduced Walt’s signature product. Caught by one of his own bullets, he finally collapses on the floor of his enemies’ lab as Badfinger’s “Baby Blue” cues up—“Guess I got what I deserved.” Before Walt carries out this fantasy—a fantasy he understands he might not survive—he says good-bye to his wife and admits to her he at last understands his own motivations. He might have chosen to pursue different solutions to the problems disease brought his family, but he instead embraced a poetic project that enlivened him with its treacherous possibilities. “All the things that I did, you need to understand,” he tells his wife. She interrupts him before he can finish: “If I have to hear one more time that you did this for the family…” He stops her. “I did it for me,” he says. “I liked it. I was good at it, and I was really…I was alive.”

Walt’s final transformation figures one violent, painful version of the return to historical self-consciousness that left critics desire. We might today understand, as Gilligan’s twenty-first-century Whitman comes to, that poetry—destructive, creative, and interested—has helped to make the world what it is. If we can accept that imagination already organizes reality, producing for the New Gilded Age pervasive inequality and cruel magic, we might recover out of this admission a sense of how the same kind of activity might organize life differently. Mad Men and Breaking Bad induce us to acknowledge activities that present themselves as inevitable and natural are in fact historical and poetic. Don and Walt are not the left’s hero poets, capable of imagining new ways of being or improved democratic forms of human association. They are neoliberalism’s poets. But because they themselves eventually recognize that, these mad, bad poets incite us to imagine better ones.

***

Racheal Fest teaches and writes about US literature and culture from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. Areas of special interest include poetry and poetics, modernism, contemporary popular culture, and the history of literary theory and criticism. She teaches at SUNY Cobleskill and Hartwick College.

***

NOTES

[1] See Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, trans. by Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014). Economist Paul Krugman uses the phrase “New Gilded Age” in his review of Piketty’s book. See Paul Krugman, “Why We’re in a New Gilded Age,” review of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, by Thomas Piketty, New York Review of Books, May 8, 2014, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2014/05/08/thomas-piketty-new-gilded-age/. Louis Uchitelle uses the same phrase as early as 2007. Louis Uchitelle, “The Richest of the Rich, Proud of a New Gilded Age,” New York Times, July 15, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/15/business/15gilded.html.

[2] See Brett Marin, Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution from “The Sopranos” and “The Wire” to “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” (New York: Penguin, 2013). For a critical account of the “prestige television” narrative Marin and others elaborate, see Michael Newman and Elena Levine, Legitimating Television: Media Convergence and Cultural Status (New York: Routledge, 2011).

[3] Critics online and in the academy interpret Walt’s choice of the alias “Heisenberg” many ways. Alberto Brodesco gives an account of the most popular in “Heisenberg: Epistemological Implications of a Criminal Pseudonym,” in “Breaking Bad:” Critical Essays on the Contexts, Politics, Style, and Reception of the Television Series, ed. David P. Pierson (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014), 53–72.

[4] Academics might recognize Walt admires the handsome edition David S. Reynolds edited for Oxford University Press on the 150th anniversary of Leaves of Grass.

[5] Key influences for Whitman include Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, vol. 7 of The Collected Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, eds. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985) and Friedrich Schelling, Philosophy of Art: An Oration on the Relation between the Plastic Arts and Nature, trans. A. Johnson (London: J. Chapman, 1845). Whitman reviewed Coleridge in 1847. See Robert J. Scholnick, “‘The Original Eye:’ Whitman, Schelling and the Return to Origins,” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 11, no. 4 (1994): 174 – 99, for an account of Whitman’s European influences.

[6] Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass (New York: Penguin, 2005), 10.

[7] Ibid., 12 – 13.

[8] Ibid., 13.

[9] Walt Whitman, “What are inextricable from the British poets,” 1857, http://whitmanarchive.org/manuscripts/marginalia/annotations/duk.00169.html.

[10] Critics have often noted the limitations and shortcomings of Whitman’s democratic project. See, for instance, my interview with Donald Pease, “Legacies of the Future,” boundary 2 45, no. 2 (forthcoming, May 2018).

[11] Matthew Weiner, “The Hobo Code,” Mad Men, season 1, episode 8, directed by Phil Abraham, aired September 6, 2007, AMC. Compare Don’s statement to Margaret Thatcher’s infamous assertion, “there is no such thing as society,” in Douglas Keay, “Aids, Education, and the Year 2000!,” Women’s Own, October 31, 1987, http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689. See John Kenneth Galbraith, The Affluent Society (1958), in The Affluent Society and Other Writings, 1952–1967 (New York: Library of America, 2010), 345–606. Galbraith further indicts advertising’s role in market design in The New Industrial State (1967), in the same volume, 607–1020.

[12] Matthew Weiner, “The Good News,” Mad Men, season 4, episode 3, directed by Jennifer Getzinger, aired August 8, 2010, AMC.

[13] Matthew Weiner, “The Other Woman,” Mad Men, season 5, episode 11, directed by Phil Abraham, aired May 27, 2012, AMC.

[14] Recent social sciences research agrees with Don. See Jill M. Sundie, Douglas T. Kenrick, Vladas Griskevicius, Joshua M. Tybur, Kathleen D. Vohs, and Daniel J. Beal, “Peacocks, Porsches, and Thorstein Veblen: Conspicuous Consumption as a Sexual Signaling System,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (November 1, 2010).

[15] See Matthew Weiner, “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” Mad Men, season 1, episode 1, directed by Alan Taylor, aired July 19, 2007, AMC. An advertising consultant mentions Sigmund Freud’s “death drive” in the pilot, and Don is disdainful. Freud has long been compatible with market logics, however, as Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays demonstrated in the early twentieth century.

[16] See Peter Sloterdijk, Rage and Time: A Psychopolitical Investigation, trans. Mario Wenning (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

[17] Vince Gilligan, “Breaking Bad Creator Vince Gilligan Answers Fan Questions—Part I,” AMC, http://www.amc.com/shows/breaking-bad/talk/2013/10/breaking-bad-creator-vince-gilligan-answers-fan-questions-part-i.

[18] Ibid., 26.

[19] Friedrich Hayek, The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).

[20] Raymond Williams, “Advertising: The Magic System,” in Culture and Materialism (New York: Verso, 1980), 177.

[21] Ibid., 180.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid., 194

[24] Ibid., 187

[25] Ibid., 189, emphasis added.

[26] Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), 20.

[27] Use and abuse of drugs (illicit and prescription) has increased in the US since the medical profession normalized prescription opioid use in the 1990s. Opioids today vie to take back from “religion” the title “the opium of the people.” See US Department of Health and Human Services, “The US Opioid Epidemic,” https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/.

[28] See, for example, Vince Gilligan, “Open House,” Breaking Bad, season 4, episode 3, directed by David Slade, aired July 31, 2011, AMC.

[29] In Matthew Weiner, “The Gypsy and the Hobo,” Mad Men, season 3, episode 11, directed by Jennifer Getzinger, aired October 25, 2009, AMC; Vince Gilligan, “ABQ,” Breaking Bad, season 2, episode 13, directed by Adam Bernstein, May 31, 2009, AMC.

[30] Matthew Weiner, “Person to Person,” Mad Men, season 7, episode 14, directed by Matthew Weiner, aired May 17, 2015, AMC.

[31] Matthew Weiner, “The Rejected,” Mad Men, season 4, episode 4, directed by John Slattery, aired August 15, 2010, AMC.

[32] Vince Gilligan, “Granite State,” Breaking Bad, season 5, episode 16, directed by Peter Gould, aired September 29, 2013, AMC.

[33] Vince Gilligan, “Open House,” Breaking Bad, season 4, episode 13, directed by Vince Gilligan, aired October 9, 2011, AMC.

[34] Vince Gilligan, “Cat’s in the Bag,” Breaking Bad, season 1, episode 2, directed by Adam Bernstein, aired January 27, 2008, AMC.

[35] Vince Gilligan, “Phoenix,” Breaking Bad, season 2, episode 12, directed by Colin Bucksey, aired May 24, 2009, AMC.

[36] See William Carlos Williams, Spring and All (New York: New Directions, 2011).

[37] See Vince Gilligan, “Felina,” Breaking Bad, season 5, episode 16, directed by Vince Gilligan, aired September 29, 2013, AMC.

No Comments