There is a small detail near the ending of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness that in the midst of the dramatic dialogue between Marlow and Kurtz’s Intended is often missed by readers. That detail is the grand piano that stands “massively” in the corner “like a sombre and polished sarcophagus.” The silent piano is, if you will pardon me, the elephant in the room, quite literally a sarcophagus with keys lined with ivory culled from African elephants in areas like the Belgian Congo in which Kurtz has pursued a career as an ivory trader. I must admit I didn’t quite notice the piano or its significance for many years, even though the text highlights the horrors of the ivory trade and particularly its human toll. The piano at the end of this text, and as Thomas Dilworth has recently reminded us, the game of dominoes which is referred to at its opening, both rely on the acquisition of ivory and speak to its saturation in the life of Victorian England.[1]

Over the course of the mid to late nineteenth century, the piano became the symbol of middle-class domesticity not only in England and Europe but also in the United States. As Mary Burgan has noted, “Of all the luxuries available to the middle classes in the nineteenth century, the piano was perhaps the most significant in the lives of women; it was not only an emblem of social status, it provided a gauge of a woman’s training in the required accomplishments of genteel society. Its presence or absence in the home could be a sign of social climbing, security of status or loss of place.”[2]

A particularly poignant example of such significance of the piano in mid-nineteenth century domesticity can be found in a letter written home to her sister in Connecticut by an American woman, Sarah Cheney, who was then residing in Zanzibar:

I often wish I could hear the Music Box or touch the dear old Piano – go back! go down! tears must not, shall not come to view! Ah well, when I come home with my loved husband and (God willing) child, we will be happier together than ever before. Mr Horn has very kindly told George to assure me of his willingness and pleasure to have me come whenever I please and play so long as I may wish upon his piano (July 11th, 1853).[3]

In all the letters penned by Sarah that are available to us, at no point does she reach the level of sentimentality she touches at this moment, remembering her piano back home in Connecticut and suppressing her tears. The irony of the situation was perhaps not even fully evident to her – or if it was, it certainly does not make its way into any of her letters. She had found herself in Zanzibar as a newly married bride, setting up her first home with her husband George A. Cheney who had recently entered the growing trade in ivory, a trade spurred by the rapidly increasing commercial demand in household pianos. George had been introduced to the trade by none other than Sarah’s father, Rufus Greene, himself a prominent ivory trader.

The presence of American traders like Greene and Cheney in mid-nineteenth century Zanzibar likely surprises most contemporary Americans since so much of our relation to Africa is historically implicated in the horrors of transatlantic slavery and the triangular trade. But Americans have also had ties to Africa that go beyond that particular history and that more West-African oriented geography. In a manner that might strike us as surprising, American merchants, particularly from Salem, played a disproportionately significant role in Zanzibar’s trade with foreigners. So significant was this trade that the United States Congress ratified a treaty with Zanzibar’s ruler, Sultan Said, on June 30th, 1834, giving the United States a favored-nation status. A US Consul, Richard Waters of Salem, took office on the island in 1837. George Cheney’s entry into this scene, then, was a relatively late one.

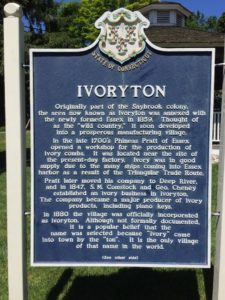

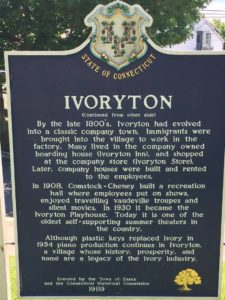

George Cheney spent almost a decade (1850-1859) going back and forth between Connecticut and Zanzibar purchasing ivory. When he decided to settle back in Connecticut he purchased a part of the S.M. Comstock Company in a village in Essex county that is now called “Ivoryton.” A plaque that welcomes tourists into the town notes, in part: “S.M. Comstock and Geo. Cheney established an Ivory business in Ivoryton. The company became a major producer of ivory products, including piano keys. In 1880 the village was officially incorporated as Ivoryton. Although not formally documented, it is a popular belief that the name was selected because ‘ivory’ came into the town by the ton>” Indeed, according to some estimates, between 1870 and 1900 the Comstock, Cheney & Company processed around 200,000 tusks that had been imported from East Africa.

George Cheney spent almost a decade (1850-1859) going back and forth between Connecticut and Zanzibar purchasing ivory. When he decided to settle back in Connecticut he purchased a part of the S.M. Comstock Company in a village in Essex county that is now called “Ivoryton.” A plaque that welcomes tourists into the town notes, in part: “S.M. Comstock and Geo. Cheney established an Ivory business in Ivoryton. The company became a major producer of ivory products, including piano keys. In 1880 the village was officially incorporated as Ivoryton. Although not formally documented, it is a popular belief that the name was selected because ‘ivory’ came into the town by the ton>” Indeed, according to some estimates, between 1870 and 1900 the Comstock, Cheney & Company processed around 200,000 tusks that had been imported from East Africa.

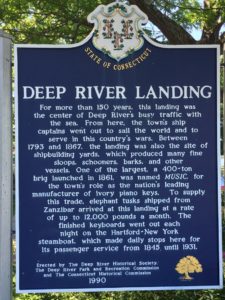

Don Malcarne, who has studied the company’s records, notes that “between 1891 and 1903, it processed almost a million pounds of soft ivory and a quarter of a million pounds of hard ivory.”[4] If the continued growth of Comstock, Cheney & Company developed Ivoryton into what has been labelled a “company town” based on the model of “welfare capitalism,” in the nearby town of Deep River, a competing firm, Pratt, Read & Company also had a voracious appetite for African ivory. Starting around 1850 until around the great depression when economic pressures forced changes in operations and the merger of the two companies, it is estimated that 90 percent of ivory imported into the United States came to these two companies. The river landing at Deep River remembers this history by remarking upon an 1861 brig named “Music,” “for the town’s role as the nation’s leading manufacturer of ivory piano keys. To supply this trade, elephant tusks shipped from Zanzibar arrived at this landing at a rate of up to 12,000 pounds a month.”

Don Malcarne, who has studied the company’s records, notes that “between 1891 and 1903, it processed almost a million pounds of soft ivory and a quarter of a million pounds of hard ivory.”[4] If the continued growth of Comstock, Cheney & Company developed Ivoryton into what has been labelled a “company town” based on the model of “welfare capitalism,” in the nearby town of Deep River, a competing firm, Pratt, Read & Company also had a voracious appetite for African ivory. Starting around 1850 until around the great depression when economic pressures forced changes in operations and the merger of the two companies, it is estimated that 90 percent of ivory imported into the United States came to these two companies. The river landing at Deep River remembers this history by remarking upon an 1861 brig named “Music,” “for the town’s role as the nation’s leading manufacturer of ivory piano keys. To supply this trade, elephant tusks shipped from Zanzibar arrived at this landing at a rate of up to 12,000 pounds a month.”

Walking around the towns of Deep River and Ivoryton, one sees remnants of this history. The pain is less visible. The building that served as the factory of Pratt, Reid & Co. is now a fancy condo complex called “Piano Works” with elephant ornamented railings (see photos). Ivoryton has a local shop named “Elephant Crossing” and has a street named “Ivory.” In the local history museum and archive in Deep River one can see the ivory cutting machine first invented by Phineas Pratt (Sr) in 1788 (see photo).

It was this machine that shifted the production of ivory goods into an industrial rather than purely artisanal operation and allowed for the massive expansion of scale. In the back garden of the society’s building there is on exhibit a small replica of a “bleaching house” in which after being placed in hydrogen peroxide the ivory keys would be placed in the sun for around thirty days.

In the archives of Ivoryton’s local history collection, I find an undated letter with an attached list of recommended readings, written to the librarian Robbi Storms, about how best to come to terms with the town’s history. Recognizing the horrors of the ivory trade for the herds of elephants, the letter foregrounds as well its human toll: “It is easier to show an interest in the environmental side (diminishing elephant herds etc.) because it is a problem that is familiar to us in the United States. It is more difficult to identify with various social upheavals of groups of people that seem very foreign to us. I hope these recommendations help to fill in the historical realities Africans faced as the demands of our factories brought wealth to our area. There is, after all, a real connection between a widow in Africa looking for a new husband to protect her from the dangers that resulted from the international trade in East Africa and the wealth brought by that same international trade that built the Ivoryton Playhouse.”[5]

What the letter refers to is the intimate relation between the ivory trade and the human slave trade as it developed in Central and Eastern Africa. Because the tse-tse fly made load bearing animals impractical in that environment, and because railroads and other mechanized forms of transportation were yet to be developed, the task of carrying the heavy tusks from the interior of Africa to the coast and the island of Zanzibar lay on the backs of Africans captured as slaves. The treacherous nature of the journey from the interior to the coast was noted by many observers including David Livingstone and Henry Morgan Stanley. Livingstone estimated that for every tusk that made it to the coast five Africans had been either killed or enslaved. Those who survived the journey to the coast were sold off as slaves to work on the spice plantations of Pemba and Zanzibar or sold off to other areas in the Indian Ocean world. George Cheney would surely have seen the slaves and the slave market on the island of Zanzibar but there is no evidence I could find in any of the journals that he kept (available at the Connecticut River Museum’s archive), or in any of the letters that Sarah wrote giving testament to the practice.

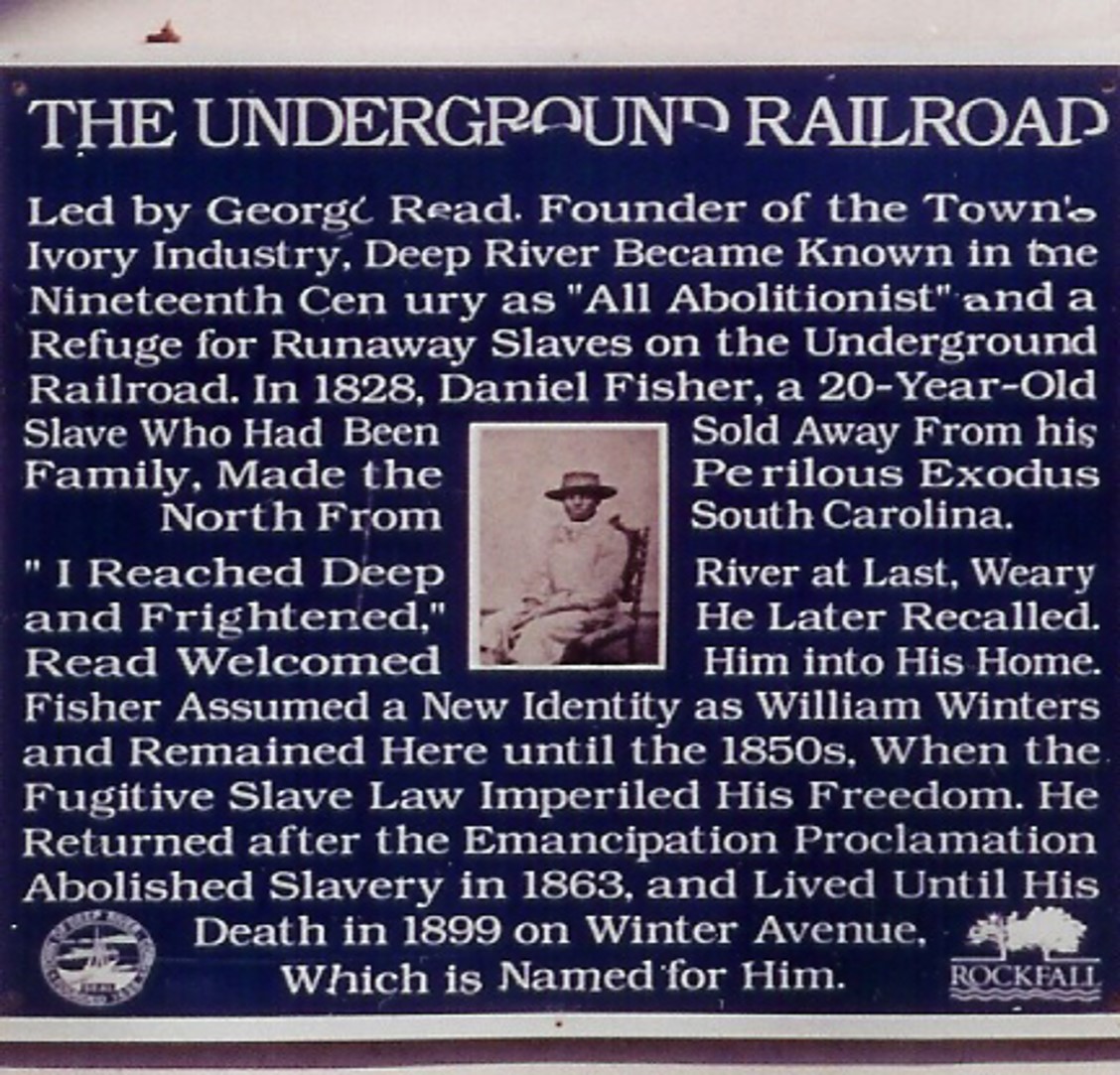

One final marker: on the corner of Main Street and Winter Avenue in Deep River there is a plaque that records the arrival of Daniel Fisher, a twenty-year old fugitive slave from South Carolina. He is taken in and provided shelter by “George Read. Founder of the Town’s Ivory Industry.” The town of Deep River, the plaque tells us “became known in the nineteenth century as ‘All Abolitionist’ and a refuge for runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad.” Read, founder of a company that was so central to the ivory and human trade in Africa, was an ardent abolitionist at home.

To those of us who were taught to believe that slavery was only a Southern problem, recognizing the complicities of Northerners, and indeed even those who were ardent abolitionists on the domestic front, with forms of human and animal devastation elsewhere should strike a somber note. We may never know exactly how much, in what detail, and when George Read and his fellow ivory manufacturers in Connecticut knew of the horrors of the ivory trade. We do know that at least one ivory trader who had participated in the trade after the turn of the century published a book in 1931 exposing those horrors.[6]

The one thing I know for certain is that I will never again miss that piano in the background of Conrad’s text and will always point to its presence when I teach the text again. Introducing this very American history of the trade in ivory will mean reminding students that Conrad’s text is not just about the Belgian Congo or about England, but also, very directly, about the United States. And thinking about this history is an open invitation to all of us to examine our own current complicities in oppressive practices far and near — even the ones to which we think we are already alert.

***

[1] Thomas Dilworth, “Dominoes and the Grand Piano in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” The Explicator, 71(4), (2013): 325-327.

[2] Mary Burgan, “Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth Century Fiction,” Victorian Studies, 30(1), (Autumn 1986): 51-76. (on 51)

[3] Letter of Sarah Cheney, July 11th 1853; Sarah Cheney Letters; Connecticut River Museum Archives. Emphases in original.

[4] Don Malcarne, “The Village that Elephants Built” in Robbi Storms and Don Malcarne, Around Essex: Elephants and River Gods. Arcadia Publishing, 2001: 48.

[5] Letter to Robbi Storms from Kate Deluna, no date. Box 1, Folder 5, Ivoryton Local History Collection.

[6] E.D. Moore, Ivory, Scourge of Africa. Harper and Brothers, New York, 1931.

No Comments