By PHILLIP R. POLEFRONE

Almost a thousand people stand on Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano in our solar system, and watch as an ice asteroid leaves a gash in the newly minted Martian atmosphere. The asteroid has been commandeered by UN-approved robotic ships that have landed and converted the material of the asteroid itself into fuel, altering its trajectory for this calculated near miss. The assembled crowd aren’t in it for the fireworks, though. They are a thousand among many Earth expats who have undertaken every project conceivable to turn Mars into a surrogate for Earth, the planet humanity has exhausted. This ice asteroid will inject valuable heat and water into the Martian atmosphere, bringing it one step closer to being able to support life—even as it takes the planet one step further from what we think of as “Mars.”

By the end of Red Mars, the first in Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars Trilogy, we have witnessed atmospheric alterations as modest as the cultivation of ever-hardier bacteria and as audacious as drilling enormous holes through the Martian crust to tap the heat closer to the planet’s core. By the end of the third book (Blue Mars), humans native to Mars lounge on the beach of a Martian ocean. But just as important to the novel’s mission as these atmospheric changes are the economic, political, and philosophical shifts that come with them. The creation of an atmosphere can only happen by facing the challenge of deciding what a Martian constitution will look like, or, more relevant to my purposes, of adapting Earth-based understandings of environmental activism to a planet without a biosphere.

By the end of Red Mars, the first in Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars Trilogy, we have witnessed atmospheric alterations as modest as the cultivation of ever-hardier bacteria and as audacious as drilling enormous holes through the Martian crust to tap the heat closer to the planet’s core. By the end of the third book (Blue Mars), humans native to Mars lounge on the beach of a Martian ocean. But just as important to the novel’s mission as these atmospheric changes are the economic, political, and philosophical shifts that come with them. The creation of an atmosphere can only happen by facing the challenge of deciding what a Martian constitution will look like, or, more relevant to my purposes, of adapting Earth-based understandings of environmental activism to a planet without a biosphere.

“Science fiction” and “sustainability” seem made for each other: both are vexed terms, and both arguably take on too much. The most serious examples of both require us to think through the intersections of technology, ecology, sociopolitical systems, and the place of the human in the universe. At the intersection of these two fields, Robinson uses the space of the “dead” planet as a laboratory for social-ecological experiments, both testing the limits of our environmental concepts and imagining the possibilities of human development without the constraints of Earth’s particular biosphere. I want to isolate one product of this experimentation in particular for discussion here, namely, the role of technology in what we might call the novel’s “ecotopian imaginary,” or the utopian social ecology its narrative creates.

I raise this topic not for its own sake, nor to participate in terraformation fantasies (much as I’d like to), but to consider the place of technology in utopian environmentalism and environmentalist discourse more generally. It has a particular importance as the state of the planet risks degrading beyond the point at which merely preventing further destruction, though necessary, is likely to be sufficient in dodging catastrophe. Much discussion of technology in environmentalist discourse, however, has been understandably suspicious of any technological “fix” to problems that many see as the fault of technological development in the first place. Perspectives that emphasize technological development are often seen as (and often are) “Promethean,” or in other words, based in the Baconian premise that “nature” is something to be mastered and bent to the human will. We are therefore left in a difficult bind. We may need an environmentalism capable of integrating industrial-scale technologies, but we can hardly be expected to trust the technophilic thinking that got us here in the first place.

The Mars Trilogy contains the beginnings of a reconciliation. Robinson depicts a relationship between technological innovation and ecological stewardship that could redefine “green” technology from being merely less destructive alternatives to being methods and tools by which humans actively promote the development of robust ecosystems. The perspective his narrative creates gestures beyond the Promethean, defining the usefulness of a particular technology in terms of its benefit to nonhuman natures rather than the other way around. It also recognizes the dangers inherent in capitalist appropriation of “greening,” and the ecological dangers of geoengineering projects conceived as vehicles for capital investment. But at the center of this perspective is a more basic unity: the confluence of ecological, technological, and social imaginaries to form a critical ecotopianism.

But before I can talk about any of this, I have to talk about robots.

***

“Robotics” in Robinson’s hands looks considerably different from the more familiar version associated with, say, Isaac Asimov—humanoid robots who are made to serve in the way humans serve, and whose fictional instantiations are sometimes taken as proxies for class struggle or enslavement.[1] In much of Robinson’s work, robots appear in the form of mobile industrial machinery that places an unfathomable transformative power in the hands of the programmer. These robots are rarely discussed in themselves, existing almost as a lacuna where labor and exploitation usually lie, between intention and realization. But what we do know is that a small group of people are able to effect the enormous transformations necessary for human inhabitation of Mars, and that most of their “work” is in deciding what ought to be changed and how. Robotic machinery, in other words, both frees the colonists up to imagine alternative material environments and gives them the power to make those environments actual. The specific interface between human and robot Robinson establishes creates a space in which the ecotopian imaginary becomes narratively visible.

We never get to see what the human-robot interface looks like, exactly, but it can be inferred that it combines high-level human input to establish the broad strokes of a plan with intelligent automation to take care of the details—and that it is not a transmission of information specifying where to place each plunge of the drill. As is required for “intelligence” in any artificial system, the details are determined by the robot receiving and interpreting feedback from the material reality it encounters.[2] The result is that human “creation” and transformation are merely a matter of communicating some feasible thing one wants to happen, but doing so in a structured way a robot can understand. The actual labor is reduced to making a good plan and figuring out how to relate it. In this particular industrial army, to put it another way, everyone is a general.

One example of this process has already been presented—the robot landers that capture an ice asteroid and bring it into the Martian atmosphere. Very little of this process is seen in the novel itself, but one of the more explicit examples comes in a moment of crisis near the end of Red Mars. Someone sabotages a water station that taps into a large aquifer, and the hydrostatic pressure beneath the surface of the planet threatens a catastrophic explosion that would create the first Martian ocean where a major town used to be. Any hope of preventing this disaster relies on their ability to collapse an overhanging cliff onto the site of the break, containing the pressure and plugging up the hole—and to do so within a matter of hours. Nadia, a character particularly occupied with construction, takes over:

During the ride over she had directed all the town’s construction robots from their hangar to the foot of the north wall, next to the water station; when the two rovers got there, they found a few of the faster robots had already arrived, and the rest were grinding over the canyon floor toward them. There was a small talus slope at the foot of the cliff…. Nadia linked into the earthmovers and bulldozers and gave them instructions to clear paths toward the talus; when that was done, tunnelers would bore straight into the cliff…. The slower robots arrived, bringing an array of explosives left over from the excavation of the town’s foundation. Nadia went to work programming the vehicles to tunnel into the bottom of the cliff, and for most of an hour she was lost to the world.

One of the more detailed acts of construction in the novel, this moment is a particularly telling portrait of what human labor looks like in the early stages of Robinson’s Mars. If we want to know what Nadia actually does, we can just look at the verb phrases of which she is the subject. By the time the cliff is brought down, Nadia has “directed,” “linked into,” and spent several hours “programming,” all of which can be summed up by the phrase “gave them [the robots] instructions.” Meanwhile, the robots were “grinding” out their efforts “to clear paths,” “bore straight into the cliff,” and thereby “tunnel” their way to Nadia’s intended result. Nadia does the thinking, the robots do the work.

No surprises here. But it’s important to note that the robots are more intelligent than mere tools, fundamentally changing the nature of the human user’s interaction with the machine. The ability to “clear a path,” imagined from a programmer’s perspective like Nadia’s, would require an ability to take in and synthesize feedback (in this case, debris) encountered along the way, freeing the programmer from the necessity of accounting for each rock along the way, as she would in, say, a bulldozer. The same is true in any of the tasks to which the industrial robots are set, because so many of them contain shifting or unknown variables. The division of labor Robinson imagines therefore relies on advanced systems in two areas: networks of communication for the transmission of instructions and complex intelligent systems to allow those instructions to remain on a high level of abstraction, excluding the minutiae of each step.

This latter point, maintaining a high level of abstraction, is important, because doing so keeps the instructions to the machine in the language of the human imagination. In programming, a “level of abstraction” refers to the specificity with which a program is elaborated, from “move all the files into that folder and rename them one through ten” (high level of abstraction) to the same instruction in binary, which refers more directly to the charge of the bits on the disk that will achieve the same result (low level of abstraction). We can apply this to Nadia’s own process of programming as the difference between telling a robotic machine to “build me a house” (highest) and programming each movement and manipulation of the machine’s apparatus (lowest). Narratively and robotically, the level of abstraction in this human-robot communication is such that we see the plan form in the characters’ minds, thus understanding how these transformations to the environment will take place before “seeing” it in materially realized. As readers of these moments, we come to assume any concrete transformation to the environment that can be imagined can be made to happen because the language of action and imagination are kept on the same plane. Imaginative events blend with physical events, both narratively and in the lives of the characters.

This latter point, maintaining a high level of abstraction, is important, because doing so keeps the instructions to the machine in the language of the human imagination. In programming, a “level of abstraction” refers to the specificity with which a program is elaborated, from “move all the files into that folder and rename them one through ten” (high level of abstraction) to the same instruction in binary, which refers more directly to the charge of the bits on the disk that will achieve the same result (low level of abstraction). We can apply this to Nadia’s own process of programming as the difference between telling a robotic machine to “build me a house” (highest) and programming each movement and manipulation of the machine’s apparatus (lowest). Narratively and robotically, the level of abstraction in this human-robot communication is such that we see the plan form in the characters’ minds, thus understanding how these transformations to the environment will take place before “seeing” it in materially realized. As readers of these moments, we come to assume any concrete transformation to the environment that can be imagined can be made to happen because the language of action and imagination are kept on the same plane. Imaginative events blend with physical events, both narratively and in the lives of the characters.

Of course, most of these acts of imaginative and physical “creation” don’t look so much like destruction. Though this particularly violent moment of transformation is useful in revealing the narrative mechanism for linking thought and action, in most ways it is anomalous. Moments of crisis-aversion are few and discrete, whereas patient construction is continuous and defines the trilogy. The same methods that Nadia uses to plug up the punctured aquifer are used by all of the first hundred colonists to build their settlements and pursue their terraformation efforts. Communal shelters are built out of bricks from automated “brick factories,” which are set up to convert the materials at hand in the inorganic rock surface of the planet (the regolith) into a usable form. Most exciting (if also most improbable) is the ability “to construct soil just like they had…magnesium bars” by converting leftover nitrogen into fertilizers that can be mixed with the rocky regolith, supplementing soil from Earth and organic material from greenhouses with these human-produced mixtures. This process, too, entails communicating the plan for constructing soil to a series of robots, now in the form of factories, but it is not a matter of pounding rocks into particularly useful shapes or collapsing geographical structures. It is the quiet work of creating the foundations for life, work that is usually automatic but not planned, the product of millennia of material flows. Robinson’s colonists translate their careful attention to nonhuman natures into construction projects that will allow those natures to flourish.

For this translation to work narratively, the industrial robots have to be programmable in a relatively short amount of time by a single person. We have to be able to witness the attention to nonhuman nature and its instantiation as a plan in order to fully realize the shape of an ecotopian imaginary, and this witnessing is easier when it’s focused on a single subject. Robinson directs our attention to the plan rather than the execution, allowing us to imaginatively short circuit the robotic laborers and suppose that “thinking makes it so.” Eliding the grittier engineering problems is a recurring fantasy in Robinson’s work, even if he never loses sight of the material constraints his characters face. It is a fantasy that is most clearly expressed in his most recent novel, Aurora (2015), when one character, admiring someone with a special aptitude for engineering, exclaims: “So she fixes things by thinking about them!” What is “fixed” in the Mars Trilogy is most often the inability of the atmosphere to support life.

The vision of one who “fixes things by thinking about them” could be taken as a neat encapsulation of the utopian imaginary—not surprising, given that the phrase comes from one of the only self-identified utopian authors extant.[3] Focusing his utopian thinking on the material flows between the human and its surroundings, Robinson develops his version of an ecotopian imaginary, elaborating a speculative social ecology in which a (mostly, eventually) democratic process informed by ecological principles is allowed to determine the formation of the ecosystems that contain it. But he puts that same ecotopian capacity in the minds of his characters—and supplements it with the means necessary for meaningful environmental praxis—by using robotic technology as a narrative device for translating thought into physical transformations. The multiplicity and variety of his characters’ ecotopian visions allow what are usually philosophical debates to play out in the laboratory of the material world. But at least on Mars, an ecotopian imaginary’s only bridge to reality is formed by accepting the role of highly transformative material technologies and mobilizing them in pursuit of alternative social ecologies. It may not put it too strongly to say that he uses his robotic technologies to make the Martians’ ecotopian imaginaries matter.

As I’ll discuss, this conclusion is considered in the context of Earth as well as Mars. Creating the conditions for an ecology where those conditions do not exist already, as is the case in Mars terraformation, is not so different from imagining fixes where the conditions necessary for life have been stripped away. But when the question of highly transformative material technologies is reframed in terms of Earthling environmentalism, things get much more complicated.

***

Breaking the barrier between human thought and environment; unlimited powers of environmental transformation—all of this might sound like nature is something to be conquered by science, human ingenuity, and ever-more-developed tools. At the very least, isn’t it anthropocentric? The environment is, after all, being changed to be more friendly to the human. Not to mention that the vast determining power put in the hands of an individual organism seems anathemic to anything approaching ecology, in which, as a fundamental tenet, everything affects everything in a complex web of interconnections.

Robinson’s form of environmental thinking can be difficult to reconcile with environmentalist discourse more broadly because of a longstanding tendency to align technology or “technological fixes” with natural exploitation and human domination of the natural world—that is, to bundle technological development with what is often called a “Promethean” perspective of the environment. It’s a term that comes up in many ecological critiques of Marxism that are uncomfortable with the continued relevance of evolving means of production in his work, critiques that Paul Burkett and John Bellamy Foster have effectively rebutted.[4] But a look at some more direct definitions of the term from an environmentalist perspective shows that technology itself is not inherently Promethean. As John Dryzek defines it, it refers more to an economic understanding of the human-nature relationship:

Prometheans have unlimited confidence in the ability of humans and their technologies to overcome any problems presented to them—including what can now be styled environmental problems….In their more extreme moments, Prometheans believe that a total control of nature is within our grasp, once nature is fully understood….[5]

Prometheanism justifies endless growth with a belief that any limitations can ultimately be overcome by the total transmutability of matter (here is where technological fixes come in), creating an inexhaustible supply of natural resources. We can just invent our way out of any problems a high-consumption lifestyle might create, says the Promethean—and therefore, there’s no reason to reduce consumption or worry about exploitation. Other understandings of the term are similarly economically inflected. Foster traces it back to Proudhon, for whom Prometheus was a figure exemplifying the triumphal human translation of nature into economic value.[6] The more definitions one reads, the more Prometheanism actually comes to sound like another name for capitalism.

Even if these are essentially arguments about economic perspectives of nature, their emphasis on technology has led to some slippage between critiques of the Promethean perspective and technology itself. Dryzek points out that Prometheans talk about nature as though it is a machine, made of “simple components—ultimately, simple resources” that can be “pieced together” to fix any problem.[7] Among the assumptions Dryzek brings into the orbit of a technocentric approach to nature is that nature is “seen in inert, passive terms,” language that resonates with other similar critiques.[8] All things considered, it’s hard to imagine, say, a deep ecologist being very excited about factories that grind an environment into its component parts and spit it out, brand new and inherently changed, on the other side.

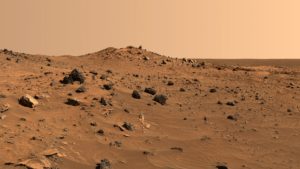

But what would a deep ecologist do with a planet that doesn’t have an ecology, that might actually be best understood as, if not dead or inert, then at least without life? The environment of Mars makes the relevance of concern for nonhuman natures much more complicated, and it forces us to ask some difficult questions about what the goals of environmental activism ultimately are, on any planet—a question with clear implications for the environmental ethics of technology.

Robinson stages this debate by embodying it in distinct characters, political affiliations, and ideologies, all of which can be summed up as a debate between the “reds” and the “greens.” Red and Green might translate to communist and environmentalist on Earth, but on Mars it indicates one’s support either for the maintenance of Mars in an untouched state or for the propagation of life and a robust ecology. It is a question that we simply have no need to pose without Mars or a planet like it, because on Earth there is no difference between these two goals. Introducing the Martian environment into the discussion, though, forces us to ask: when we talk about conservation, is it limiting the human’s impact on its environment (full stop) that we care about? Or do we care about limiting human impact only insofar as it impedes the propagation of nonhuman life?

Robinson stages this debate by embodying it in distinct characters, political affiliations, and ideologies, all of which can be summed up as a debate between the “reds” and the “greens.” Red and Green might translate to communist and environmentalist on Earth, but on Mars it indicates one’s support either for the maintenance of Mars in an untouched state or for the propagation of life and a robust ecology. It is a question that we simply have no need to pose without Mars or a planet like it, because on Earth there is no difference between these two goals. Introducing the Martian environment into the discussion, though, forces us to ask: when we talk about conservation, is it limiting the human’s impact on its environment (full stop) that we care about? Or do we care about limiting human impact only insofar as it impedes the propagation of nonhuman life?

Perhaps for tactical reasons, conservationism on Earth usually leans heavily on destruction or disruption of nonhuman life as the reason to care about human influence on the ecology. But without any life to speak of, the “conservation” framework gives way to the question of whether purposive human determination of its environment is fundamentally unethical or distasteful. The debate plays out in Robinson’s novel most explicitly between Sax (Saxifrage Russel, whose namesake is, to William Carlos Williams, “my flower that splits / rocks”) and Ann Clayborne (whose surname seems to imply that she is the rock to be split). Sax is the main proponent of terraformation by any means necessary, while Ann advocates minimizing human impact in order to promote the study and admiration of Mars as it is. Sax’s argument is predictably life-centric:

The beauty of Mars exists in the human mind…. Without the human presence it is just a collection of atoms, no different than any other random speck of matter in the universe. It’s we who understand it, and we who give it meaning…. That’s what makes Mars beautiful. Not the basalt and the oxides.

…And yet the whole meaning of the universe, its beauty, is contained in the consciousness of intelligent life. We are the consciousness of the universe, and our job is to spread that around, to go look at things, to live everywhere we can. It’s too dangerous to keep the consciousness of the universe on only one planet, it could be wiped out. …If there are lakes, or forests, or glaciers, how does that diminish Mars’s beauty? I don’t think it does. I think it only enhances it. It adds life, the most beautiful system of all.

Ann’s response is curt.

I think you value consciousness too high, and rock too little. We are not lords of the universe. We’re one small part of it. We may be its consciousness, but being the consciousness of the universe does not mean turning it all into a mirror image of us. It means rather fitting into it as it is, and worshiping it with our attention. …You’ve never even seen Mars.

Neither the argument for nor against environmental transformation is given a definitively privileged position in the trilogy, which is clearly much more interested in the tension between them. While Sax’s ultimately carries the day, it is also clear that his perspective is in more danger of being complicit with capitalist exploitation of human and environment alike by transnational corporations, dubbed the “transnats.” Unlike on Earth, where intentional environmental alterations are usually made to better access resources, the pro-transformation argument on Mars is most directly committed to the propagation of a healthy ecosystem. In contrast, the anti-transformation argument, which on Earth is framed as promoting a healthy ecosystem, precludes any ecosystem at all in the Martian context. The Promethean argument is turned inside out: it is no longer meaningful to speak of human technologies dominating nonhuman life when technological intervention is necessary for nonhuman life to flourish. Where “nature” fits into this argument becomes a very complicated question indeed, but it is at least as much what the colonists make room for as what they draw from. It is just as certainly not subsumed by markets, as “growth” has reverted to its original meaning, referring to bacteria instead of GDP.

Taken up and brought back to Earth, these questions force us to reconsider what a “green” technology might look like, and how it might be defined. Thus far, technologies dubbed “green” minimize impact, defined as “environmentally friendly” in the degree to which they limit their transformation of the environment around them. And rightly so when a healthy global ecology exists, as under these conditions limiting transformation is indeed coextensive with promoting nonhuman life. One would be hard pressed to find reputable ecologists willing to describe the Earth’s global ecology as “healthy” in 2016, however, so some sort of additional consideration is called for. The dead planet is a particularly useful figure on a dying planet for this reason—not only as a cautionary tale, but also as a space to think through our approach to the parts we have already killed.

If we grant that there is nothing theoretically impossible about a technology that is both transformative and proponent of a more robust ecosystem, we might start considering whether a “positive” green technology, one that makes changes for the better in addition to limiting changes for the worse, can and should be pursued on Earth. It would not be a matter of “improving on nature” (another charge sometimes leveled at technology instead of Prometheanism), but of creating the conditions in which “unimproved” nature can best flourish.

Robinson invites us to consider this time and again in his terraformation novels, as his extraterrestrial expats arrive on Terra only to realize that Terra itself has come to need terraformation. Indeed, Aurora, written two decades later, can almost be read as a response to potential misappropriations of the Mars Trilogy that would cite terraformation as an alternative to taking care of the Earth. The novel chastises expansionist views that would take the fantasy of going somewhere else as permission to forget about the planet of one’s origin, to which he repeatedly suggests one is inextricably bound. In several cases (2312, Aurora) Robinson’s terraformers participate in some form of large-scale ecological restoration on Earth combined with the differently challenging, intellectual work of adapting their ecological consciousness. These projects do not result in a perfect reconstruction of some Edenic, pre-human state; the flooded landscapes that host them make this impossible. Nevertheless, these Terran ecological restoration projects look promising, and their promise relies on an ability to deploy on their home soil the technologies and knowledge developed for extraterrestrial terraformation—not to mention a version of environmental praxis that combines technological innovation with ecological thinking.

Among the most notable aspects of this reworked, anti-Promethean vision of technology is the space it creates for the development of an ecotopian imaginary. If it is permissible to consider large-scale transformation of lifeless or dying environments in order to promote the (re)generation of nonhuman life there, some positive vision of what is technically possible and ecologically desirable will be required. It is essential to condemn simple greenwashing of actually Promethean approaches to technology, to oppose technological fixes that take unconscionable risks with human and nonhuman life, and to recognize that “transformation” can just be unfettered economic growth in a flimsy disguise—the Reds (Earthling and Martian) are right about that. But it is also worth asking if (and when, and how) it is possible to repurpose the means of destruction that have been unleashed on this environment to help it begin repairing itself, even if the technologies that are appropriated were developed with solely economic growth in mind. Robinson seems to think it might be, even where doing so won’t keep things as they are or return things to precisely how they were. If he’s wrong, fine—he remains a utopian. But if he’s right, he makes the space for some ecologist who “fixes things by thinking about them” to make quite a difference indeed.

***

Phillip R. Polefrone is a PhD candidate in Columbia University’s Department of English and Comparative Literature. He works on the digital humanities, the environmental humanities, and 20th-century American fiction.

***

Notes

[1] See Gregory Jerome Hampton’s take, for example, in a recent interview by Eric Molinsky. Molinsky, Eric. “The Robot Uprising.” Imaginary Worlds 41: 2016. Web. 30 May 2016.

[2] My thinking on this version of robotics has been influenced by Norbert Wiener’s classic discussion of cybernetics in The Human Use of Human Beings: “For any machine subject to a varied external environment to act effectively it is necessary that information concerning the results of its own actions be furnished to it as part of the information on which it must continue to act. …This control of a machine on the basis of its actual performance rather than its expected performance is known as feedback” (24). Weiner, Norbert. The Human Use of Human Beings. 1950. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988. Print.

[3] In his recent article, “Remarks on Utopia in the Age of Climate Change,” Robinson explains himself: “despite my uneasiness concerning utopias as a literary genre, I have nevertheless been writing them for a long time. I am one of the very few serial offenders, you might say, at least in modern times.” Robinson, Kim Stanley. “Remarks on Utopia in the Age of Climate Change.” Utopian Studies 27.1 (2016): 1-15. Web.

[4] See Burkett’s Marx and Nature and Foster’s Marx’s Ecology. Foster, John Bellamy. Marx’s Ecology. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000. Print. Burkett, Paul. Marx and Nature: A Red and Green Perspective. 1999. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014. Print

[5] Dryzek 45-50. Dryzek, John. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses. New York: Oxford UP, 1997. Print.

[6] See Foster 129.

[7] Dryzek 52.

[8] Carolyn Merchant’s Radical Ecology does not use the term Promethean or Prometheanism, but in a section on “Experimental Science” she echoes this language of lifelessness: “During the seventeenth century, the organic framework…was replaced by a new experimental science and a worldview that saw nature not as an organism but as a machine—dead, inert, and insensitive to human action.” Merchant, Carolyn. Radical Ecology: The Search for a Livable World. London: Routledge, 1992. Print. 42.

No Comments