By R.H. LOSSIN

I am not going to attempt to justify sabotage on any moral ground. If the workers consider that sabotage is necessary, that in itself makes sabotage moral. Its necessity is its excuse for existence. And for us to discuss the morality of sabotage would be as absurd as to discuss the morality of the strike or the morality of the class struggle itself. –Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

***

If it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, it is perhaps even more difficult to imagine social alternatives without the machinery that capitalism has invented. This might be due to the fact that capitalism per se is an abstraction whereas the assembly lines, cars, smart-phones, milk cartons and gas range stoves that result from a capitalist system of production are not. It takes a rather more forceful act of the imagination to disappear the innumerable apparatuses that one encounters between morning coffee and an office cubicle, classroom, or commercial kitchen than it does to envision a world in which everyone has equal access to the same devices. This is not to say that material and political equality is simple in theory or practice, but that our political imagination seems to find its limits in our attachment to technology. As the art historian Max J. Friedlander has famously remarked “it’s easier to change your worldview than how you hold your spoon.”

There has been some very good journalism concerning the impact of networked, computerized tools designed for the micro-taylorization of worker activity and the deleterious effects of profit-maximizing scheduling algorithms on the lives of service sector employees. But on the whole the attitude towards technology is the same as it has ever been under capitalism—namely, that it is neutral stuff that could also be put to work for good. But while technology itself has no agency and therefore no political or economic agenda (an obvious and stupid point that I would rather not have to make), the care that critics take not to critique technology itself is striking. Whether technology could or should do this or that is almost entirely beside the point. What it does should be of concern and what it often does is eliminate pesky human workers who make demands and renders those workers who are not eliminated financially precarious and miserable. As David Noble succinctly put it, we are suffering from “a fatalistic and futuristic confusion about the nature of technological development.”[1]

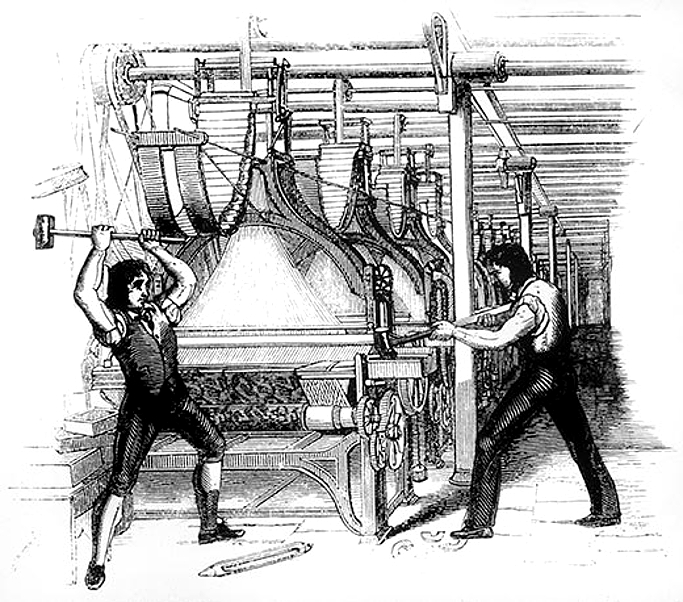

The contemporary use of the word “Luddite” is instructive. Now meaning an irrational dislike of all things new, Luddites historically are best known as machine breakers–smashing the stocking frames, gig mills and automated looms that threatened not just their employment and wages, but a culture built around small shops, cottage industries and craft guilds. The Luddites were active at a transitional moment (roughly 1812-1817) that saw rapid industrialization alongside the adoption of laissez-faire economic policies. Their response was to attack the machinery itself. It is the destruction of machinery that has made the Luddite uprisings one of the most frequently referenced worker revolts in the history of industrial capitalism and also one of the most maligned. Luddites occupy a uniquely contradictory position in the cultural imaginary—one in which the very frequency of reference acts to suppress the historical reality of the referent. Along with being an incredibly effective way to pre-empt criticism, the contemporary use of the term “Luddite” is indicative of a cultural investment in technological progress that spans the political spectrum while consistently refusing to announce itself as political. Noble reminds us that “capital invested in machines that would reinforce the system of domination, and this decision to invest…was not itself an economic decision but a political one with cultural sanction.”[2] By smashing machines the Luddites, he suggests, “were perhaps the last people in the West to perceive technology in the present tense, and to act upon that perception.”[3]

My intention here is not to proffer a political program based on direct action, but to point out that an aversion to machine sabotage—in practice and in theory–is linked to an insufficient critique of technology and that the general weakness of such critiques is itself evidence of the symbolic and material importance of technology to a capitalist system of production. In the service of avoiding technological determinism, we are participating in its reification.

The wholesale rejection of technology is so untenable that it doesn’t merit discussion. However, this ridiculous position persistently resurfaces, not as an argument itself, but as a foil against which all pro-technology arguments appear eminently reasonable. This non-argument haunts nearly every popular critique of technology. A recent article in The New York Times, “The Machines Are Coming,” is symptomatic of the nearly universal fear aroused by accusations of Luddism. After an intelligent and critical analysis of new workplace technology that is systematically employed to reduce the power of workers through surveillance and deskilling (if not to replace them entirely), the article concludes optimistically with the following paragraph:

It’s easy to imagine an alternate future where advanced machine capabilities are used to empower more of us, rather than control most of us. There will potentially be more time, resources and freedom to share, but only if we change how we do things. We don’t need to reject or blame technology. This problem is not us versus the machines, but between us, as humans, and how we value one another.[4]

This is not untrue. Still, this paragraph is not necessary or organic to the argument. Nor does it point to any concrete reimagining of this alternate future that is ostensibly so easy to imagine. It doesn’t need to be there. The fact that it is—the persistent recurrence of these apologies—indicates a deep-seated aversion to the idea that, at our moment in history, the overall effect of technological innovation might be bad. More troubling perhaps is that we have pegged all of our hopes for the future to the same technology that is so clearly disenfranchising certain classes of people in the present.

The London Review of Books published a similar article with a nearly identical title on technological unemployment, and it ends in a similar way:

There is a possible alternative, however, in which ownership and control of robots is disconnected from capital in its current form. The robots liberate most of humanity from work, and everybody benefits from the proceeds: we don’t have to work in factories or go down mines or clean toilets…but we can…set about creating a new universe of wants….It seems to me that the only way that world would work is with alternative forms of ownership….This alternative future would be the kind of world dreamed of by William Morris, full of humans engaged in meaningful and sanely remunerated labour. Except with added robots.[5]

The recognition that technology will not be put in the service of “empowering most of us” without a radical restructuring of property regimes makes this optimism more satisfying than The New York Times version. But it still fails to address the question of whether capitalist robots could fulfill socialist ends. Jacobin Magazine’s technology issue takes a similar editorial position—to carve out a pro-technology space for the left by seeing in capitalist development “the preconditions for a post-scarcity society.”

Progress and technological progress have been so thoroughly conflated that any suggestion to the contrary seems simply insane. Marcuse put it this way: “In the contemporary period, the technological controls appear to be the very embodiment of Reason for the benefit of all social groups and interests…the intellectual and emotional refusal ‘to go along’ appears neurotic and impotent.”[6]

It is not in fact “easy to imagine” a future where technology will serve the interests of humanity at large. Imagining a future outside of our current technological configuration is extraordinarily difficult. Technology is not in itself a political agent. It has no agency. It has no class interests. However,

once the [technological] project has become operative in the basic institutions and relations, it tends to become exclusive and undermine the development of the society as a whole. As a technological universe, advanced industrial society is a political universe, the latest state in the realization of a specific historical project—namely the experience, transformation, and organization of nature as the mere stuff of domination.[7]

With the advent of social media and mobile networked devices that facilitate constant surveillance; the increasing capacity to monetize interpersonal relationships; the erosion of any division between work and leisure; and the subsumption of nearly all individual activity from banking to reading into one technological space, Marcuse’s arguments are increasingly relevant. It is no longer sufficient to think in terms of individual devices—of how one type of robot might be amenable to a socialism. Instead, we need to think seriously about the self-propelling logic of the entire technological apparatus.

Political arguments that are built on a diplomatic compromise with the technological status quo are the product of a culture so saturated in the stuff that everything is thought of in technological terms. They are not simply technological compromises but political ones as well, for “in the medium of technology, culture, politics and the economy merge into an omnipresent system which swallows up or repulses all alternatives…technological rationality becomes political rationality.”[8] Criticism of technology now appears neurotic, irrational, and anti-social.

***

Rethinking Sabotage

The symbolic destruction of property is a regular characteristic of resistance and rebellion. Some examples from France include workers shooting out the faces of public clocks during the July Revolution of 1830, the toppling of the Vendome Column during the Paris Commune of 1871, and in our lifetime, Jose Bove driving a tractor through the front of a McDonalds. The United States has, as one of its founding myths, the symbolic destruction of British tea. Protesters burnt the flag to in opposition to the Vietnam War and one of the first actions of the U.S. military upon entering Baghdad in 2003 was to pull down the statue of Sadaam Hussein. Upsettingly, but in the same vein, the Islamic state has engaged in the systematic destruction of unholy artifacts as part of its political program and theater. Property destruction is among other things a way of communicating political ideas. And yet we seem incapable of accommodating the idea that the destruction of technological apparatuses might be equally thoughtful.

What I would like to consider here is the potential significance of a form of property destruction that is not often thought of as symbolic or politically meaningful in itself—sabotage. I want to suggest that the destruction of machinery is also a means of communicating political ideas. In fact, I would like to contend that it is more than a bit strange that machine sabotage is not commonly figured in the same register as the toppling of a statue. Machinery is, after all, the most obvious physical expression of capitalism. There is plenty of precedent for the use of machinery as a metaphor for capitalism. Take, for example, William Blake’s “dark satanic mills” or Lewis Hine’s photographs of children standing against a backdrop of immense, threatening machines. The exclusion of machine sabotage from the realm of meaningful symbolic acts speaks to the cultural saturation of an ideology that figures social progress as technological progress and, in turn, represents machine destruction as irrational rather than, like flag burning for example, objectionable but meaningful nonetheless.

Sabotage—as the most extreme refusal of technology—is a fruitful point of departure for a consideration of the politics of technology precisely because of its absence from these discussions. Actual, physical technology seems to form the imaginative limit of critiques of capitalism. Even the most romantic of Marxists, such as William Morris, want to keep the machines around to fill in whatever gaps are left in the socialist future and as the level of technological saturation increases, so to does the problem of thinking our way out of particular modes of production.

The refusal on the part of the left to acknowledge the significance of machine-breaking dates as far back as Marx’s dismissal of the Luddites (they had the wrong idea about how capitalism works). It makes a strategic appearance in the Constitution of the Socialist Party of 1912, and it is visible today in the almost paranoid qualifications embedded in critiques of technology. I would like to suggest that the prima facie rejection of sabotage as a politically salient action contains and conceals the commonly held belief that technology is—even if it is, momentarily, the expression of particular social relations—essentially neutral stuff; that, by extension, this particular aspect of capitalism does not need to be “smashed”; and, in its most extreme and dangerous version, that technology itself might usher in the revolution.

It is not within the scope of this essay to determine how important sabotage was to the labor movement in practice, but its circulation as an idea was important enough for the American Socialist party to explicitly address it by 1912. Section six of the article on membership of The National Constitution of the Socialist Party declared that “any member of the party who opposes political action or advocates crime, sabotage or other methods of violence as a weapon of the working class to aid in its emancipation shall be expelled from membership in the party.” This was a strategic response to the advocacy of sabotage by the International Workers of the World as well as the recent bombing of the LA Times building. The explicit renunciation of sabotage as a negotiating tactic was a perfectly reasonable way to establish the legitimacy of the Socialist Party. But it is also a reflection of the willingness of state socialism to uncritically adopt capitalist modes of production—something that was not limited to American craft unions.

In 1914 Lenin wrote a brief article entitled “The Taylor System: Man’s Enslavement by the Machine,” where he accurately describes the implementation of Taylor’s motion studies as an oppressive means of extracting more and more value from workers by assuring that they do not lose “a second for rest.” The Taylor system, he argues, is typical of capitalism, which is wasteful in all respects save for its ability to extract surplus value from members of the working class. Lenin leaves room to conclude that Taylorism might, under socialism, bring great benefits to workers because the fruits of this increased productivity would be equitably distributed. But he stops short of making a positive argument for the Taylor system.[9] By 1918, however, he has fully embraced this management theory:

Taloyrism “is a combination of the refined brutality of bourgeois exploitation and a number of the greatest scientific achievements in the field of analyzing mechanical motions during work….The possibility of building socialism depends exactly upon our success in combining the Soviet power and the Soviet Organization of administration with the up-to-date achievements of capitalism. We must organize in Russia the study and teaching of the Taylor system.[10]

Lenin’s endorsement of the Taylor system opens a whole counterfactual can of worms that cannot be addressed here. But it also underscores the difficulty of separating industrialization—the implementation of machinery proper—from social organization. If even the Soviet system could not imagine a mode of production that incorporated the technology of capitalism without also importing a system that necessarily entails “man’s enslavement by the machine” on the level of daily experience, then who can? Whether or not equitable distribution of surplus occurs is irrelevant here. What is striking is the wholly unselfconscious admission that the adoption of capitalist technology entails an adoption of a whole system of labor based on the division of craft knowledge into distinct and simple tasks. In other words, for industrialization to be successful in the Soviet Union, the division of labor at the core of capitalist exploitation must be imported as well. Efficient machine production demands a particular type of labor—labor that is disempowered, interchangeable, a mere appendage of an apparatus. In short, alienated labor.

While alienation is not to be confused with boredom and repetition, Marx’s writing on machines indicates that technology—fixed capital—is not in fact so easily detachable from capitalism and the alienation it entails. It is in the machine that labor appears to be “transferred from the worker to capital in the form of the machine, and his own labour capacity devalued thereby…the appropriation of labour by capital confronts the worker in a coarsely sensuous form: capital absorbs labor into itself.” And it does so by way of machinery.

Progress under capitalism appears as technological progress alone because capital is crystallized in machinery, which not only appropriates the living labor of the worker but “develops with the accumulation of society’s science of productive force generally…The productive force of society is measured in fixed capital, exists there in its objective form.”[11] Marx elaborates on this, writing that it is “the tendency of capital to give production a scientific character,” and as the machine appears “opposite labor…the entire production process appears as not subsumed under the direct skillfulness of the worker, but rather as the technological application of science.”[12] But this progress by science only occurs at a later stage in capital, first labor must be appropriated “by dissection,” the division of labor into smaller and more “mechanical” components in order for a “mechanism to step into their places.”[13] The Taylor system is not new, but a refinement of the prerequisites of industrial capitalism and if this is truly the necessary condition for the existence of such highly productive technology, then how that technology can exist and function without the external political controls and conditions that shaped and maintained it becomes a serious question. In other words, it is nearly impossible to imagine how the factory and the Taylor system that comes with it could be used, in the words of our optimistic New York Times columnist “to empower more of us, rather than control most of us.”

A machine according to Marx has particular characteristics: “All fully developed machinery consists of three essentially different parts, the motor mechanism, the transmitting mechanism and finally the tool or working machine.”[14] Whether or not the physical strength of the worker must be employed to set the machine in motion is not important for him.

The machine…is a mechanism that, after having been set in motion, performs with its tools the same operations as the worker formerly did with similar tools. Whether the motive power is derived from man, or in turn from a machine, makes no difference here. From the moment that the tool proper is taken from man and fitted into a mechanism, a machine takes the place of a mere implement.[15]

Machines, then, are characterized by a widening of the space between the worker and the product. They embody, in their very form, the alienation of the worker from the products of their labor. And to the extent that the “natural” tendency of machinery is to become ever more complex, to incorporate an increasing number of tools and formerly human operations, technological progress is the material progression of alienation. Social forms might exploit the worker and convert their labor into surplus value, but alienation is not static—it progresses and expands, and it does so by way of machinery and automation.

Machinery opens up this space between the worker and the product of their labor by exceeding the organic limitations of the worker. “The number of tools that a machine can bring into play simultaneously is from the outset independent of the organic limitations that confine the tools of the handicraftsman.” [16] In this way as well, machines actively establish the alienation that inheres in a capitalist system of production. Machines are dehumanizing not because they mimic the individual laborer, but because they can always do more at once—because at the point of production they confront the worker with his generality. In the machine, workers are confronted with the fact that they are not simply replaceable as individuals, but merely the individual expression of productive forces in general—they are not only interchangeable with machines but interchangeable with each other. There is no space in machine production for empowerment and creativity.

Instead, through mechanization, the industrial revolution, by replacing tools with machines, reduces the worker to an energy source. The real operation of “the handicraftsman’s implement, in this case the spindle, which is first seized on by the industrial revolution, leaving to the worker, in addition to his new labour of watching the machine with his eyes and correcting its mistakes with his hands, the merely mechanical role of acting as the motive power.”[17] Alienation from the products of one’s labor is a result of capitalism, but the reduction of workers to mere motive power is a material and mechanical process that cannot be dismissed as a mere excrescence of property regimes.

Mike Davis has pointed out that “in contrast to the A.F.L.’s narrow defense of endangered craft privileges, the [International Workers of the World] were virtually unique among American labor organizations….in their concrete plan for worker control.” It is not coincidental, he argues, that they also regularly advocated sabotage as a means of obtaining this control. The IWW was also unique in their recognition of the crucial role that machinery played in the exploitation and control of workers. Their manifesto echoing Marx’s writing on the relationship between workers and machines begins as follows:

Social relations and groupings only reflect mechanical and industrial conditions. The great facts of present industry are the displacement of human skill by machines and the increase of capitalist power through concentration in the possession of the tools with which wealth is produced and distributed.

While calls for worker ownership of the means of production are not a unique position among Marxists, the IWW program of industrial unionism was unique in emphasizing the centrality of machinery to the organization of the capitalist class. “The employers’ line of battle and methods of warfare correspond to the solidarity of the mechanical and industrial concentration.”[18] Implicit in the manifesto is the suggestion that society is not only organized according to classes but according to an increasingly integrated and totalizing machine logic. Sabotage—either direct interference with the mechanisms of production or a collective withdrawal of worker efficiency in some other form—is not in this scenario an irrational or desperate action. If capital is increasingly organized around, and expressed by mechanization, then sabotage constitutes an articulate, meaningful collective action that expresses a will to power. Unlike other forms of protest, sabotage directly addresses the fact that fixed capital—machinery—plays an indispensable role in the maintenance of class power that is articulated through these acts of destruction.

The careful avoidance of the machine question by many intellectuals is a symptom of an ideology that mistakes progress in general for technological progress and thereby hitches itself to a whole host of carefully concealed interests. It is not possible to disavow technology as such, but it is possible to begin thinking about the relationship between technology and power in a way that does not make facile assumptions concerning the neutrality of the subject at hand. Machinery, like the built environment, inscribes and enforces social decisions and interests and the eagerness with which critics come to the defense of the subject of their own critiques plays a role in this enforcement.

***

R.H. Lossin is a librarian and PhD candidate in Communications at Columbia University. She has written for The Nation, Jacobin, Jstor Daily, and The Huffington Post and is a regular contributor to The Brooklyn Rail.

Notes

[1] David Noble, Progress without People: In Defense of Luddism, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr (1993), 2.

[2] Noble, 6.

[3] Noble, 4.

[4] Zeynep Tufecki, “The Machines are Coming,” The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/19/opinion/sunday/the-machines-are-coming.html

[5] John Lanchester, “The Robots Are Coming,” The London Review of Books, 37(5), 21.

[6] Herbert Marcuse, One Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society, Boston: Beacon Press (1964), 18.

[7] Marcuse, 11.

[8] Marcuse, 12.

[9] V.I. Lenin, “The Taylor System” Put Pravdy 35, March 13, 1914, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/mar/13.htm.

[10] V.I. Lenin, “The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government” (1918), Collected Works, vol. 27. Quoted in Harry Braverman, Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, New York: Monthly Review Press (1998), 9.

[11] Karl Marx, The Grundrisse, 694, thenewobjectivity.com/pdf/marx.pdf

[12] Marx, 699.

[13] Marx, 704.

[14] Marx, 494.

[15] Marx, 495.

[16] Marx, 495.

[17] Marx, 496.

[18] The Manifesto of the International Workers of the World, http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/iwwpreamblemanifesto.html

No Comments