By Mary Lawlor

The following excerpt comes near the end of Mary Lawlor’s memoir Fighter Pilot’s Daughter: Growing Up in the Sixties and the Cold War (Rowman & Littlefield 2013). The setting is Paris in the spring of 1968. In the previous September, Lawlor, the dutiful Catholic daughter of an American military family, had moved to the city to begin studying at the American College in Paris. Her father, Jack, stationed that fall in Heidelberg, Germany, is now in Vietnam, flying missions against the Vietcong. The writer’s perspective has shifted dramatically over the course of her time in Paris, where she has befriended leftists, musicians, artists, and, as the episode shows, draft resisters from the US. Alarmed at the changes she learns her daughter is going through, Frannie, the writer’s mother, recently called her back to Heidelberg with the idea of keeping her there. Instead, Mary has gone back to Paris to rejoin her friends.

The following excerpt comes near the end of Mary Lawlor’s memoir Fighter Pilot’s Daughter: Growing Up in the Sixties and the Cold War (Rowman & Littlefield 2013). The setting is Paris in the spring of 1968. In the previous September, Lawlor, the dutiful Catholic daughter of an American military family, had moved to the city to begin studying at the American College in Paris. Her father, Jack, stationed that fall in Heidelberg, Germany, is now in Vietnam, flying missions against the Vietcong. The writer’s perspective has shifted dramatically over the course of her time in Paris, where she has befriended leftists, musicians, artists, and, as the episode shows, draft resisters from the US. Alarmed at the changes she learns her daughter is going through, Frannie, the writer’s mother, recently called her back to Heidelberg with the idea of keeping her there. Instead, Mary has gone back to Paris to rejoin her friends.

***

Readers’ Responses to Fighter Pilot’s Daughter

Late in 2013 I published a memoir about growing up in a military family, Fighter Pilot’s Daughter: Growing Up in the Sixties and the Cold War. The central characters of the book, apart from myself, were my parents, Jack and Frannie, who spent decades moving from post to post in the US and Europe with my three sisters and me in tow. By the time the World Trade Center came down in 2001—when the cold war really became a thing of the past—they had both passed away. I wrote the book as a kind of self-therapy as well as a memorial to them and the passing of their time. I also wanted very much to relate the central drama of my youth—the clash between me and my father in Paris, May 1968 when I was involved with demonstrations against the war he was fighting.

In writing Fighter Pilot’s Daughter, I hoped to draw on the legions of military “brats,” as the children of the armed services fondly call themselves, for part of my audience. The book is partly structured by what we have in common: the incessant moving—in my family’s case every two years; the gazillion schools—I went to fourteen by the time I went to college; my mother’s hard times as a soldier’s wife; and the difficulties of living with a warrior father.

In the wake of publication I did indeed hear from lots of readers who grew up in the military and from boomers in general who had visceral responses to the cultural climate evoked in the book. But another group of readers emerged that I hadn’t so much counted on: veterans of Vietnam and earlier wars struck by the family portraits in Fighter Pilot’s Daughter. It was these former military men who offered the most surprising responses.

The boomers shared memories of what look in retrospect like the loopy trademarks of the cold war domestic landscape. One woman wrote about the missile silos she visited with her girl scout troop, manifestations of American power that were meant to inspire patriotism but fueled nightmares instead. Another described neighbors who built bomb shelters but seemed “sheepish” about them, as if they knew how crazy they would appear to people outside the community of bomb shelter owners. A man who as a boy read J. Edgar Hoover’s Masters of Deceit told of finding himself ostracized in summer camp for knowing, from this book, too much about communism.

These readers were eager to share their recollections of the gloom and angst of daily life during the cold war. Some wrote eloquently about the habits of fear and uncertainty we took from the old duck-and-cover days. It was as if they hadn’t had the chance to talk about them for years, if ever—even though narratives about and set in the cold war have been around for years. I like to think Fighter Pilot’s Daughter evoked for them a sense of the steady, low-grade trauma-in-waiting we lived with for so many years. Or maybe they went for the book because, like me, they’re always looking for stories that stir up any memories of that time, the time of our youth.

Some readers tried out comparisons between the old climate of suspicion—of the closeted communist or McCarthyite down the block (and perhaps in one’s own heart)—and the distrust in our own time of religious radicalism. The comparisons do and don’t work, but it’s been interesting to see how strong the impulse is to keep the cold war in view as a template for measuring very different geopolitical and cultural situations. How hard it is to let go of habits of thinking that map the world for you.

Unlike others of their generation, the service daughters and sons I heard from grew up with the cold war right outside the doors of their “quarters.” Our fathers literally manned the frontlines of the global struggle, and we lived with the secrecy and disciplined panic they brought into our living rooms. Or should I say our vertiginous sequence of living rooms. We’re part of a vast population, a subculture of sorts, with only the slimmest sense of home. Military progeny aren’t recognized much as a category, partly because we were raised to blend in with whatever community we happened to inhabit (developing a Zelig complex is one way of dealing with the constant fact of moving). What many of us greatly desire, consciously or not, is acknowledgment of the displacement we’ve experienced too many times and the feeling of never belonging, not to mention the referred traumas of living under the same roof as a warrior—whether he’s on active duty or in the reserves or retired or dead.

My book necessarily offers some of this recognition. It joins a small library of narratives (not including those written for children and young adults) about military brats and family life. The list might include Sarah Bird’s novels The Yakota Officer’s Club and Above the East China Sea, Pat Conroy’s Santini books, Susan Wiggs’s The Ocean Between Us, Siobhan Fallon’s You Know When the Men Are Gone; Donna Musil’s film Brat’s Our Journey Home and Tony Richardson’s Blue Sky; David Mamet’s TV series The Unit, and Katherine Fugate’s Army Wives. I’m surely neglecting several important stories, but even if they were here, the inventory would be small for a population of over fifteen million military brats. (See bratsourjourneyhome.com and militarybrats.com.)

One fellow Army daughter recognized in my description of my parent’s “chin-up” attitude under hardship her own perceptions as a girl of the instability behind her father’s “genial authority.” His way of dealing with this instability was to “fake it ‘til you make it.” He’d hold his chin up and chest out as if there were no doubts—and did this until his character fairly rested on the solid conviction of his own and the nation’s invincibility. Because he went on faking it until the end, my reader never got to know her father well; and this, she felt, was representative of the way many of us related to soldier fathers. I recognize the profile, as did many of the vets who responded to the book. Like I mentioned earlier, these were the people who surprised me most.

I had actually figured as the book went to print that any military personnel who got their hands on it would object, particularly to the section devoted to my time in Paris from 1967 to 1968. In those chapters, I elaborate my not so gradual relinquishing of Catholic girlhood ethics for a world of leftists, draft resisters, hash smokers, and devotees of exotic spiritual styles. The climax is Paris, May 1968, when I joined the world-shaking demonstrations against, among more primary targets, the American war in Vietnam. My dad, stationed in Saigon at the time, was flying combat missions as a Cobra helicopter pilot. His sudden appearance in Paris to rescue me from the company I was keeping infuriated, shocked and confused me in ways that had long-lasting repercussions.

One of the veteran-readers whose communications moved me so much was a retired Air Force pilot. His wife and two children were uprooted for decades by his assignments around the world. He sent me an email out of the blue to say he was captivated by the book’s pictures of daily life when my father was away; and by the stormy drama of his return. Dad’s long distance gaze, his caged movements, and the striking impression that he didn’t belong at home—these images struck the reader like mirrors of his own past and set him reflecting on himself as a warrior father. He praised the book and wished it—and me—well. Later he published a very positive review in Military Magazine.

Another fighter pilot who actually worked with my father got in touch with me by email, and we later spoke on the phone. Being in contact with this man was jarringly like being in contact with Dad himself. He was still reading the book when I first heard from him, and I found myself more than a little tense about how he’d react to the Paris chapters. I gave him a head’s up as to what he’d find there. I wasn’t taking notes, so I can’t recall exactly what he said, but it was something like we all have to go through what we have to in becoming who we are; that discord is important for young people coming into their own. He made me very happy with expressions of amazement at the accuracy of the family portraits I drew; and then narrated episodes in his own family’s history when ruptures like mine made him realize that love needs to let go as well as hold on.

I can’t say much more about what these ex-pilots felt or the particular details of their responses to my book. They didn’t, in fact, say much beyond what I’ve just described. Philosophical differences about war and empire may stand between us, but they made me realize how much I held to certain fixed ideas about what career military people are like. And did so in spite of the fact that my vision of my father shifted over the years as he retired, entered AA and became a much kinder and gentler version of his older self. In spite of the fact that he’d regularly check my mom’s denigrations of any critics of American military policy. In spite of the fact that he welcomed my war-protesting, draft-dodging, left-wing husband into the family as warmly as he did my sister’s West Point educated, officer husband.

One day, when mom, talking to my husband, was literally damning the mothers who had encouraged their sons to resist the draft, Dad checked her: “Frannie,” he said. “Remember, we were professionals.” I was struck by the “we,” which expanded the idea of service to include military families as well as fighters. And I loved Dad’s readiness to defend my husband’s very different life trajectory. But I also found my self wishing he’d been as tolerant of difference back in ’68, when his rage met mine and the altercation ended in physical violence.

But this was the 90s, not the 60s. He had changed and come to understand the political, even cultural, views of people quite different from himself. And I had just written about this experience, had thought about it a great deal in the process. So why were those cartoons of military men still in place? I see in my own habits of mind that the icon of the rigid, unthinking soldier is still there, that I haven’t let go.

Curious how the responses to Fighter Pilot’s Daughter that struck me most weren’t from my co-generationists or the kids and spouses of service people who went through the same things I did, but Army and Air Force pilots struck by the story of a fellow flyer’s daughter, of what she went through growing up under the shadow of Mars, standing in the kitchen door.

***

21 – OUR FRIENDS THE DRAFT RESISTERS

With their circle of supporters enlarged, the [American draft resisters who came to Paris from Madison, Wisconsin in the early spring of 1968 and organized a union] started pushing public relations overtly. They held speaking events and rituals of turning in draft cards. One night at the end of April, Valery, Liza, and I tagged along to a public meeting on the left bank. The hall was packed. The three of us found seats in the back. The stage was bare except for a long table with microphones. Somebody came on and introduced the Madison group. Our friends [the draft resisters] stood at their seats in the front and bowed to the audience. Applause rose in waves.

The room settled down. Two men appeared on the stage and took seats at the table. One of them had a rather striking wall eye, visible behind his horn rimmed glasses. His thinning hair was plastered back, revealing a subtle widow’s peak. A whisper went past. Sartre. In the other chair was Alfred Kastler, 1966 Nobel laureate in physics.

Kastler, whose research had made important advances in the study of atomic structures, spoke against the war and, as he had in the past, against the threat of nuclear proliferation. Then the philosopher began to speak, and the room went silent. He praised the resisters. Directing his funny gaze at them, Sartre pronounced the words that brought everybody to their feet. “Vous êtes vraiment existentialistes.” While the crowd roared and the room shook with applause, the resisters filed on stage, placing their draft cards in a box destined for the dumpster. From stage left, they faced the audience, their faces gleeful, stoic, embarrassed….

In the aftermath of the public meeting, the draft resisters’ union support grew. Drawn to the story of Sartre’s tribute, students, ordinary citizens, expats, came to their aid. Fund raising was going well. They set up an office. Rallies were planned. Somebody gave them a hand press to make posters and flyers. The publicity was largely aimed at making known the atrocities in Vietnam and the growing resistance of the American population…..

***

23 – MAY 1968

… 1968 roars like a beast on the far side of a dense jungle. It’s hard to distinguish the sounds, almost impossible to see the contours. Every memory I have seems to add another story, pile more onto the heap of anecdotes, images, interpretations accumulated over how many decades now. How can anything in this mess be trusted? Trying to find a way back, I find pictures from newspapers, lines from books and films stuffed between the events of my life. Scenes of political action against the war are stacked beside photos of dope smoking hippies doing nothing, but doing it in style. There are speechmakers, the long hair held back in headbands, Native American style. On other stages, the music screams, Oh say can you see….

The resisters had made a decision to join the student groups that were planning demonstrations against university policies and other issues that were growing hot in Paris, foremost among them the American war in Vietnam.

Their relationship to the student movement would be complicated. [It was in large part directed against] the same French government, of course, that had extended a hand to give the US draft resisters a legal home outside the states. Our friends would be entering darker waters and risking their security again, for this would not be just another demonstration. It would be big. It would last throughout the spring, and it would make history….

[D]uring the first week of May, Liza, Valery, Roy, Joel, and I took the Metro to the Latin Quarter. The indecisive spring had finally mustered a sunny morning. We climbed out of the Metro at Place St. Michel. Lots of people were already gathered there, in clusters, waiting for things to happen….

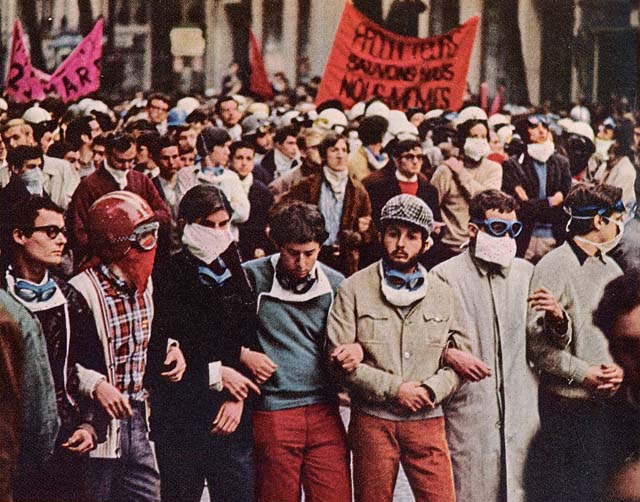

By the afternoon the tension was palpable. Blue-gray police buses had arrived, and a shiver of attention ran through the crowd. The fiesta subsided. The moods of the demonstrators would alternate like this throughout the days ahead: joy, fear, anger, an infectious stoicism running like waves across a bay. Now the uniforms drew a palpable fear. They meant a vengeful French government, and at the controls was the massively powerful Charles de Gaulle.

The police were made to sit inside the busses for what would be hours, getting hotter and more frustrated while the demonstrators shouted slogans of the Situationists and the Enragés. When the cops were finally released, dozens of black helmets spilled from the buses, like a pool of oil. Quickly the black formed a long, even line. All you could see were their mouths, set tight beneath the hot helmets. With shields and sticks ready, the cops faced the jeering crowd, their discipline barely holding. Students taunted from across the Place St. Michel: “What if we burned the Sorbonne?” “Under the paving stones, the beach.”

In one imperceptible moment the flics were released on the crowd. The air shifted instantly. The tension on their side, the mix of nervous comedy and anger on the demonstrators’, all this blew up in a hot, terrifying avalanche of movement. Students ran in every direction, towards the cops, away from them, into the narrow side streets.

Demonstrators began prying cobblestones loose from the rue St. André des Arts. Within moments others joined them: the venerable rocks of the street itself went flying at the police. The cops ran at the crowd, pursuing what had become an actual battle.

The Place was in mayhem, and my friends disappeared in the fray. Liza went one way, Roy and Val another. Things moved quickly, and I ran with the crowd. Before the chaos, we had somehow made our way around the perimeter of the square to the western edge. I wanted to get back to the Place St. André, thinking the others would eventually turn up there. That would require making my way through the Place St. Michel again. It would be like crossing an ocean at night in a storm. Now, as a troop of police came running up, I dashed inside a café near the corner. Some thirty seconds passed before the waiter locked the door. I thought he would make the few of us who were there leave, but he didn’t. For the next hour I drank coffee and wrote in my notebook about the action boiling in the street outside…

My memories of Paris that month inevitably lead me to the locked café where I sat writing, separated from the rioting crowd and my brave friends. While Dany the Red and the Sorbonne Student Union, the draft resisters and everybody there threw their bodies at the police, I sat aside the danger, encased in glass, scribbling to myself. I had alienated myself from the throbbing heart of the revolution by opting for the café. Writing came to mean a coward’s act. It was a chair before a small table with iron legs, surrounded by glass doors and windows sealing off the chaos outside. When I ask myself why, the answer floats up, familiar and insistent: fear. The sight of violent disorder and the electric passions in the air sent me scurrying for cover. Who knew what would happen? Would we end up in jail? Would we get deported?

Vague images of Heidelberg, my parents, the clipped military language, came and went like warnings: memories of what I’d been taught to think was right. For the moment, the threatening Other to the left bank uprising wasn’t the cops or de Gaulle or the minister of education but the lines and squares of home, the disciplines and expectations that I was violating in every possible way, just by being here.

I’d like to think that dismissing myself as a useless, disconnected, observer is as reductive as honoring all who enter the fray, finding them each heroic in word and movement, sacrificing themselves for the greater good. I want to think these medallions are too simple. They don’t reflect the complicated reasons why people join political movements, what they feel, what they offer.

But what I’d like to think isn’t, in fact, what I think. It isn’t what I feel. That was a decision, made those forty some years ago, to stay on the perimeter of the square. It can’t be revoked. At some point in the recent past, I started trying to let up a little on the old indictment, the cartoon of myself as a dilettante stopping in the café. A different picture,

I thought, might be possible. It would be of an eighteen-year old daughter of a military family whose vision of ideology was taking shape during one of the most ideologically intense moments, in one of the most ideologically dramatic scenes, of the later twentieth century. The wavering emotions, the fears and exaltations, the affiliation and voluntary isolation would be those of a person trying to figure out what political meant and, at the same time, how the political thinking and acts of her friends would bear on her ever-emerging self. The politics that had saturated life in our apartment in rue de Parme and exploded at St. Germaine in May had stirred me up in ways I would never have been able to imagine a year earlier. But the conflicting influences of the Lawlor-Walsh family would soon challenge the lessons of the Paris streets. The threat would come not just from inside my own conscience. It would show up in the very real fact of my father, based in Saigon, turning up in Paris…

***

24 – SHOWDOWN WITH JACK

The mail room at the American College in Paris was an oversized closet in the basement of the American church. A Dutch door separated it from the lobby, and the mail clerk could almost always be seen leaning there. Like the concierge at our building in rue de Parme, he kept an eye on all the comings and goings.

I came out of the dark stairwell into the florescent lobby and headed straight for the Dutch door. The clerk looked up from his haze and blinked, like seeing me meant something. His gaze snuck past my shoulder, across the room. I turned to see Stelman’s assistant, Thomas, sitting in his office on the other side of the lobby. He stood up slowly, buttoned his jacket, and strolled towards me. Younger than Stelman [the Registrar, a former Navy man and our nemesis], the assistant carried himself in the same stiff, military fashion. “How are you,” he said, too loud, too interested. Thomas never had time for students. His courteous air was patently phony, and I started to feel something ominous in the room. I said hello and kept moving. He stayed beside me, step for step. Mr. Stelman wanted to see me, he said. A streak of adrenaline ran up my chest. Frannie [my mother]. Of course she would have called him. He was her agent now.

Stelman sat behind his big desk, an unreadable grin on his face… “You’ve been biting your fingernails,” he observed, looking at my hands. The banality was odd: surely he had things to do. I remember thinking for a moment that since my mother had been communicating with him, perhaps he was gathering intelligence for her about my health, my state of mind. He was full of questions. Was I worried, nervous, unhappy? Was I eating alright?

The thought occurred that Stelman was keeping me for some reason when the door opened. There, out of all logic, stood my father. Everything beyond the doorway faded. His height almost reached the top of the frame, and he was thin as a pencil in his dark gray suit. The ice-blue gaze came from far away. He didn’t say anything. The room was still, but the air shook. “Hi ya, Mame,” he said finally in a half-friendly voice that didn’t match the cold eye.

They’d cornered me with small talk, and now with shock. I wanted to fight them, to stand up and hold steady. Instead I started to cry, but not before Stelman slipped out the door, a look of smug reverence on his face.

Dad gave me a hug. Six or seven feelings welled up, and I didn’t know which to hold onto. We went to the hotel where he and Frannie had stayed during earlier trips to Paris. I was already in their world again. The small room, the hard, modern lines, so bourgeois. Fleeing would do no good. Jack had called Interpol. He would only catch up with me

again, at a table in one of our cafés or in somebody’s shabby apartment. There would be a scene; I would be the child of empire in front of my friends. He seemed to know he didn’t need to keep an eye on me. The prison was in my own heart as much as in the inescapable reaches of my parents’ universe.

Dinner was, of course, strenuous. The restaurant was elegant. Dad was formal, as distant as Frannie had been the weekend before. His suit seemed alien, a costume he had to wear. He held doors for me, pulled out my chair. But he was angry and baffled at the same time. “What happened, Mame? Who are these folks?” I couldn’t answer.

Nothing I might say would make sense in his warrior’s mind. “They’re just friends” drew an abrupt “they’re no good friends.” Disappointingly, he went on. “They’re just the kind of people the Soviets want.” His look was cold and unbending. “If you don’t think they’re looking for kids to influence, you’re out in left field.” The pun wasn’t intended. The Soviets, he said, had agents all over Europe, especially at the universities.

They preyed on student organizations, hung around cafés, waited for the chance to give their spiel. The Russians didn’t have to appear themselves; they had all kinds of middle men.

The conversation was going nowhere; neither of us was willing to take the other seriously. Changing the subject, he described his trip from Vietnam, the jeep careening across the tarmac, the telegram, the flight out of Saigon. He had a good excuse, he said with a laugh, to get out of another attack mission in a Huey, the helicopter he had had a hand in arming. (Decades later he told John and me the Army had given his crew a hangar, a Huey, a bunch of ordinance, and told them to figure out how to put the two together.) Back in the chilly hotel room, I fell to bed, exhausted and ready to disappear from my father, from Paris, from myself.

When the train pulled into the Heidelberg station the rafters overhead seemed closer than they had nine months before. The steam and the screeching rails were like details from a prisoner exchange scene in a Cold War movie. The train came to a halt, and I said to myself, This is going to be awful. Jack had a month of emergency leave. He would be around all the time. The apatment on Neuenheimerlandstrasse was big, but it would be far too small for us to inhabit together.

***

28 – THE END OF THE COLD WAR

… Coming of age in the fervor of the 1960s, I lost forever Jack and Frannie’s frame of reference. The culture wars marked my generation for good. On the left we despised Ronald Reagan and viewed his administration with disdain. The right made a hero of him. We abhorred his “evil empire” rhetoric and the debt he left the nation while militarily spending the Soviets out of existence. Conservatives celebrate him as

the leader who ended the Cold War. Reagan’s successor, the first Bush president, sat in the White House as the wall came down but kept the Cold War paradigm alive in his talk about terrorism and the “new world order.” Either you were with this order or you weren’t. After September 11, 2001, the younger Bush pushed the divide between us-and-them further than his father had, bringing to office the old Cold Warriors who’d written the text for American world dominance after the downing of the Wall and of Gorbachev. The 1992 Defense Planning Policy, written by Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Cheney, Richard Perl, and others from the first Bush White House, used that same text to steer the

son’s administration, to plan global strategy from a distinctly right wing point of view. America had to dominate the earth. Challengers would have to be watched, hunted down. Like the dark generals who ran the coup against Gorbachev, they would have us turn back into the depths of a new Cold War….

Neither Jack nor Frannie lived to see September 11 or Obama’s election. Jack died from a heart attack while in treatment for non- Hodgkins lymphoma on December 23, 1993. In the hospital, barely conscious, his wrists tied loosely to the bed rails, he kept trying to lift his arms, as if desperate to fly.

Not long after, Frannie started receiving a monthly stipend from the Veterans Administration for Dad’s exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam. He had spread the stuff from helicopters over the jungles, but some of it blew back on him. It was now considered a likely cause of his disease. The burial at Arlington, a full military ritual with twenty-one-gun salute and the presentation of his coffin flag to Frannie, “on behalf of a grateful nation,” honored him stiffly. The icy graveyard was silent except for the clearing throats. The soldiers who carried the coffin maintained rigid order, their strapped chins jutting out like bayonets. They protected him and us: nobody could take advantage of our undisciplined feelings.

My parents’ last transfer was to Arlington Cemetery. Side by side, their graves overlook the Potomac. You can see the Washington Monument from the site, and in the distance the low walls of the Pentagon. On windy days in late fall, the blackened branches scrape against the white-gray sky, and their voices sound across the graveyard. They call for each other, “Frannie!” “Jack!” like they’re in different parts of the house—one of the thirty or so we inhabited. They’re both looking for something; or they’re about to have a fight. Frannie’s matter-of-fact alto and the surprising, sure lightness of Jack’s tenor have the ring of immeasurable confidence—in who they were, what America was, what it meant to be Catholic and military.

I cower and come closer, hoping to get at what they want, hoping to see who they are; wishing, more than anything, to be with them yet glad to be apart. I try not to sustain Jack and Frannie’s stark visions. I think differently, and then find those cold binaries lurking in the corners of my mind. I try to remember the feelings of our household, but there are too many shifts and changes in the stream of years to see well. The church where I had First Communion is dark inside, the blaring Alabama sun still blinding. Nancy and Lizzie’s high school graduation is a muddled compound of images from Junipero Serra, in Monterey, and Stuttgart, where they actually finished. Sarah, on a park bench in Texas in the late 1950s—is she happy or is she just squinting into the sun? The

fear, from so many directions, sneaks in and settles on each image.

School is a grid of standing formations. The voices call out memorized lines. Discipline, the protective jacket, is always there, like a blanket clung to by a child who’s too old to have it. We disguise ourselves as adults now, looking back to the days of Jack and Frannie, following and avoiding the paths they cleared for us. We follow them and stray, take different routes and loop back again to the home we always had, the sheltering pilothouse, moving in sun and storms through the choppy seas of our lives.

***

Mary Lawlor is Professor Emerita of English and American Studies at Muhlenberg College. She has written widely on identity formation among indigenous peoples. Her most recent book is Public Native America (2006).

No Comments