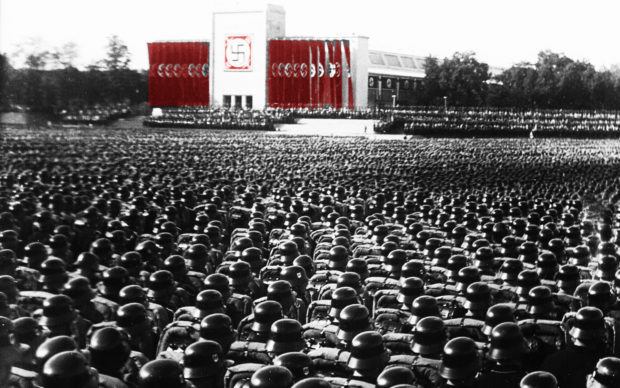

It’s hard to speak ill of a book that targets fascism. And in theory it is even harder to be critical of a book that aims to explain how fascism works and thereby saves us from its return. Even if the author is wrong, one is inclined to say, “well, at least they’re trying.” But that charity is only possible if the author is actually trying to understand fascism, and isn’t for example, repackaging conservative tropes and claiming they are the harbingers of fascism’s return. In a context when fascism actually is returning, this is tantamount to crying wolf on the south side of the village, even while the wolf approaches from the north.

To be clear, I’m no conservative, and this is no defense of conservative politics. Rather, my point is that if one wants to attack conservative politics it should be done head on, and it should be honest. Blurring the distinction between conservatism and fascism is a dangerous instantiation of Godwin’s Law. It numbs us to legitimate warnings, and it trivializes the dangers that we face.

How Fascism Works is organized into 10 chapters, each addressing a common feature of fascist ideologies (patriarchy, anti-intellectualism, anti-realism, etc.), with each chapter also drawing on examples of these features in contemporary political discourse – for example, in mainstream American political discourse (typically by Republicans). The conclusion we’re intended to draw is that this discourse is symptomatic of hidden fascist tendencies, and ultimately (as the book’s title suggests) drives the return of fascism in the United States and elsewhere. The problem is that the features of contemporary discourse Jason Stanley highlights are nearly definitional of conservative politics, and, as we will see, are unreliable indicators for fascist ideology and do not illuminate how fascists seize and maintain power.

Let’s begin with Chapter 1, which concerns fascism’s appeal to a “The Mythic Past.” It’s hard to think of a conservative American politician who hasn’t played this tune. Ronald Reagan was a master at it – painting Norman Rockwellesque pictures of earlier, simpler, better times. But that kind of nostalgia is nearly definitional for conservatism – conservatives are about conserving the status quo and maybe even being regressive, after all. Why would they not use such myths about the past? The question for us is whether this is really a strategy that fascists use. The question needs to be handled with care.

Here, right out of the gate, we learn that scholarship is not going to be a priority in this book. Stanley quotes a Mussolini speech in Naples in 1922 to support the idea that fascism is about invoking nostalgia for a mythological past.

We have created our myth. The myth is a faith, a passion. It is not necessary for it to be a reality…. Our myth is the nation, our myth is the greatness of the nation! And to this myth, this greatness, which we want to translate into a total reality, we subordinate everything.

Stanley summarizes the Mussolini quote as follows.

Here, Mussolini makes clear that the fascist mythic past is intentionally mythical. The function of the mythic past, in fascist politics, is to harness the emotion of nostalgia to the central tenets of fascist ideology…

The problem is that Mussolini was saying no such thing here. The passage does not occur in a discussion about a mythic Italian past, but in a section on the Italian army. And Mussolini is not using the term ‘mito’ in the sense of “myth.” The “miti” he is talking about are not backwards-looking myths about the past, but templates or goals for future behavior. Indeed, the translation of “mito” as “myth” is (despite superficial appearances) not optimal here. The translation in the online Biblioteca Fascista, renders “mito” as “ideal.” When the passage in question is read in context with this translation it creates an entirely different impression:

The Army. As regards the other institution in which the regime is personified—the army—the army knows that when the Ministry advised the officers to go about in civilian clothes to escape attack, we, then a mere handful of bold spirits, forbade it. We have created our ideal. It is faith and ardent love. It is not necessary for it to be brought into the sphere of reality. It is reality in so far as it is a stimulus for faith, hope and courage. Our ideal is the nation. Our ideal is the greatness of the nation, and we subordinate all the rest to this.

We can agree that the passage is canonical fascism, but I think we can also agree that it has little to do with “nostalgia for a mythic past” as Stanley suggested. The sentence Stanley elides makes this clear – the ideal is a “stimulus” (“pungolo”, literally, a prod) to future courage etc.

Of course, Mussolini certainly drew on myths about historical Rome (although he was not doing so in the passage quoted). But in Mussolini’s case it wasn’t nostalgia for Roman times (a mythic past), but rather a goal of emulating the discipline of the Roman army that inspired him. Mussolini was not imagining a golden age of toga parties and gladiator contests, but creating an army with the discipline of the Roman legions. Mussolini borrowed the Roman Fascii, but little from Roman life. Thus, Roman discipline became a forward-looking ideal for the army.

This is clear from a proclamation made by Mussolini in the same year – 1922 – “To Celebrate the Birth of Rome.”

The Rome we honor is certainly not the Rome of the monuments and ruins, the Rome of the glorious ruins among which no civilian walks without feeling a thrilling shiver of veneration […] The Rome we honor, but mainly the Rome we long for and prepare is another one: it is not about honorable stones, but living souls: it is not the nostalgic contemplation of the past, but of the hard preparation of the future. [my emphasis]

None of this is to say that fascists never make use of myths about a better, shinier, past, but often these appeals to the past are pragmatic rather than essential to fascism’s methods (that is, to “how fascism works”).

But let’s be honest: fascists are not alone in harnessing myths about the past. Every school child in the United States knows the myths of the good hardworking colonists and George Washington (“who could not tell a lie”) and the rugged frontiersmen like Davey Crocket and Daniel Boone.

Marxists too have their mythological past. Both Marx and Engels spoke of the “primitive communism” of hunter-gatherer societies – Engels devoted a considerable part of The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State to spinning this myth. Even some contemporary feminists will appeal to the myth of a matriarchal prehistory.

What is the point? The point is that everyone is apt to appeal to historical myths when convenient to do so. Fascists do it as well (or at least as shamelessly) as anyone. But their myths are really not, as Stanley insists, consistently about “a mythic past, tragically destroyed.”

A related concern arises when Stanley argues that one of the myths fascists specialize in concerns the virtues of patriarchy: “The patriarchal family is one ideal that fascist politicians intend to create in society—or return to, as they claim.”

Let’s examine this point closely, staying with the case of Mussolini’s fascism in Italy. There’s no doubt that Mussolini advocated a traditional role for women in the home – or in any case paid lip service to it. But how much of that was a political calculation to keep the Catholic Church on board, how much was driven by his obsession with growing the Italian population, and how much was inherent to the nature of fascism?

Or here’s another way to ask the question: Was patriarchy an outgrowth of fascism or was Mussolini securing power in a place that was already hyper-patriarchal? Under the Pisanelli Code, in effect prior to Mussolini, women were denied the right to vote and the right to hold public office. By contrast the initial fascist platform promised suffrage to women (before voting became moot).

Whatever might be said about Mussolini, by virtue of organizations like Fasci Femminili, many Italian women entered the political realm for the first time. Mussolini created other women’s groups, like Massaie Rurali, that got women out of the house and socializing with each other, activities previously not available to women in agricultural communities. It is also worth noting that the number of women in universities exploded during the fascist era. Alexander De Grand, in his book Women Under Italian Fascism, reports that “women constituted 3.9% of the university enrollment in the early part of the 20th Century, and that percentage grew to 17.4% in the 1930s and was 30% by the last year of the fascist regime.” In pharmacy, almost half the students were women (1,076 of 2,492). In the faculty of philosophy and letters there were 1,828 female students out of 2,783 total.

Perhaps fascism is less wedded to patriarchy than it is wedded to a certain martial attitude about whatever values it latches onto. That attitude might be summarized as “do what I say or I’ll stomp on your throat.” What I mean is that patriarchy is everywhere, so don’t be surprised if you can see it in fascism, and don’t be surprised if it looks especially dark when wearing jackboots.

Stanley also has trouble seeing the difference between garden variety Country Club Republican patriarchy and genuine fascist patriarchy. This leaves him juxtaposing quotes from Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan with those of Hutu nationalists and White nationalist Andrew Auernheimer from The Daily Stormer. He warns that Romney and Ryan say what they say “without much thought to their implication,” but one wonders. Here’s a test; I’ll put Stanley’s quote from Ryan together with a quote from Auernheimer in the article cited by Stanley, and we’ll see if you can tell which is the Republican and which is the White Nationalist.

Quote A: “Women are to be championed and revered, not objectified.”

Quote B: Don’t sit here and pretend you’re a nice traditional girl when you fight against any implementation of traditional values. Say aloud what you are, on the streets, to your families, on social media: “I’m a despicable whore.” Do it before it is too late, because I swear to whatever gods may be that when the purge comes if you have been using traditionalism as a cloak for your revolting degeneracy your name is going on a list and we will be coming to make you pay for it. You will feel the punch to your throat first, but the hours afterwards at the hands of a WHITE SHARIA gang will make that seem as just a brief and gentle touch against your skin. Your ribs will be broken. Your face will be broken. Some of you will not live to tell about it. This I promise: a much needed correction is coming for you soon, you disgusting skanks.

I’m going to assume you guessed correctly.

I agree that the quote from Ryan is patronizing and patriarchal, but is the implication of Ryan’s language really something in the neighborhood of what Auhernheimer is saying? Does blurring the distinction between traditional conservative tropes and fascist ideology to this extent actually advance our understanding of fascism?

Stanley’s argument about patriarchy leaves me wondering whether there could be such a thing as matriarchal fascism, and I have to confess that I can see no reason why there couldn’t be. In a recent video opinion piece published by the New York Times, he uses the masculine pronoun when talking about the prototypical fascist leader, adding “he, because yes it’s always a he” (Stanley’s emphasis). Have we forgotten Eva Peron already? There’s a Broadway play about her. There’s a movie based on the play starring Madonna. And let’s not forget Marine Le Pen, current President of France’s National Rally (formerly National Front) party. Or Frauke Petry, co-leader of the Alternative for Germany Party. Or Pia Kyaersgaard, co-founder of the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti).

There is a largely hidden story about the relationship between fascism and women, an example of which is when numerous suffragists joined the British Union Fascists (BUF) between the world wars. Indeed, the BUF bragged that it had more women candidates for office than any other party. Martin Durham, in his book Women and Fascism, notes that just as there’s a well-known tradition of writing women out of the history of progressive politics, so too there is a tradition of writing them out of our histories of fascism, possibly motivated by the premise that women couldn’t be fascists of their own volition. But it’s worth remembering that patriarchy expresses itself in many ways, including by denying and erasing memory of the political agency of women.

A different set of concerns arise in Chapter 9, with Stanley’s account of the European fascist fetishizing of agrarian lifestyle. As he puts it: “Whereas cities, to the fascist imagination, are the source of corrupting culture, often produced by Jews and immigrants, the countryside is pure.” He points to The National Socialist “Official Party Statement on Its Attitude toward Farmers and Agriculture” (circa 1930), in which the party sees in farmers “the main bearers of a healthy folkish heredity, the fountain of youth of the people, and the backbone of military power.”

Of course, anyone who has grown up in a rural area has heard this kind of pandering from politicians their entire lives, and to some extent it wasn’t all pandering. Meaning, it isn’t just fascists who fetishize rural life. Apart from certain Marxists (e.g. Marx and Engels on “the idiocy of rural life”), it is a nearly universal trope.

For example, there is a text by Thomas Jefferson called Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), where he infamously says that those “who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people.” Just in case you think that might be taken out of context, well here is some more context for you.

Corruption of morals in the mass of cultivators is a phenomenon of which no age nor nation has furnished an example. It is the mark set on those, who, not looking up to heaven, to their own soil and industry, as does the husbandman, for their subsistence, depend for it on casualties and caprice of customers. Dependence begets subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue, and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition. Thus, the natural progress and consequence of the arts, has sometimes perhaps been retarded by accidental circumstances; but, generally speaking, the proportion which the aggregate of the other classes of citizens bears in any State to that of its husbandmen, is the proportion of its unsound to its healthy parts, and is a good barometer whereby to measure its degree of corruption.

Long story short: in the history of the world there has never been an example of corrupt farmers, and the corruption of a state is in direct proportion to the percentage of city dwellers.

Again, we see Stanley blurring the distinction between conservatism and fascism, warning us that if we don’t mend our conservative ways we’ll be goose-stepping our way to a very bad end. His conviction seems to be that anything that moves an inch to the right of this week’s common wisdom among bleeding edge progressives is putting us on the fast train to fascism.

At times the blurring of conservatism and fascism takes on the form of unintentional self-parody, as in lines like this: “When voters in a democratic society yearn for a CEO as president, they are responding to their own implicit fascist impulses.” It doesn’t occur to him that they might want someone with experience balancing budgets. Do politicians make less authoritarian presidents? Do lawyers? Retired generals?

Another element that raises questions is Stanley’s discussion of and general hostility to free speech in Chapter 2. Stanley has long expressed his skepticism about the value of free speech, most famously when he published his “Postcard from Paris” in the New York Times, regarding the satirical French newspaper, Charlie Hebdo, exactly one day after 12 of its employees were assassinated by Islamic terrorists over what was perceived to be anti-Islamic bias.

Yet, as the staff of Charlie Hebdo was aware, there surely is a difference, in France, between mocking the pope and mocking the Prophet Muhammad. The pope is the representative of the dominant traditional religion of the majority of French citizens. The Prophet Muhammad is the revered figure of an oppressed minority. To mock the pope is to thumb one’s nose at a genuine authority, an authority of the majority. To mock the Prophet Muhammad is to add insult to abuse.

Of course, the issue isn’t whether Charlie Hebdo’s staff was being insulting or abusive – the question the day after the massacre was whether they deserved an extrajudicial death sentence. Since hostility to free speech has become a plank in Stanley’s version of the progressive platform, he claims – unsurprisingly – that if you don’t accept the plank too, you are contributing to fascism’s rise. He begins by channeling an argument from Plato.

Democracy, by permitting freedom of speech, opens the door for a demagogue to exploit the people’s need for a strongman; the strongman will use this freedom to prey on the people’s resentments and fears. Once the strongman seizes power, he will end democracy, replacing it with tyranny…

Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels once declared, “This will always remain one of the best jokes of democracy, that it gave its deadly enemies the means by which it was destroyed.” Today is no different from the past.

But this should give us pause. It’s a whole new level of Orwellian newspeak to suggest that allowing free speech is part of “how fascism works,” and that we ought to defer to Goebbels on the value of free speech. No doubt about it – fascists have bragged about exploiting free speech to undermine democracies, but there are solutions, for instance instruction in critical thinking. Instead Stanley attacks John Stuart Mill’s idea that free speech affords us a “marketplace of ideas.”

The argument from the “marketplace of ideas” model for free speech works only if the underlying disposition of the society is to accept the force of reason over the power of irrational resentments and prejudice.

Does Stanley genuinely think that Mill had no concept of irrational resentments and prejudice? As though the 19th century only saw cool rational debate? I ask because this is followed by one of the more remarkable misrepresentations of a philosophical position ever:

Mill seems to think that knowledge, and only knowledge emerges from arguments between dedicated opponents. [Emphasis Stanley’s]

Of course, Mill suggested no such thing. In fact, he was very explicit that sometimes free speech yields the opposite result.

I acknowledge that the tendency of all opinions to become sectarian is not cured by the freest discussion, but is often heightened and exacerbated thereby; the truth which ought to have been, but was not, seen, being rejected all the more violently because proclaimed by persons regarded as opponents.

There are no guarantees that the process results in zero error and zero loss of knowledge, but as Mill observed, this is not the sole goal of free speech. Mill stressed that one of the key virtues of free speech is that it chips away at our own hubris — as when we think we know something and it turns out we’re not entitled to that attitude. More importantly, Mill argued that when we engage others in defending our opinions it deepens our understanding of our beliefs and prevents them from becoming mere dogmas.

The question remains, of course, as to why Stanley thinks free speech is useless against fascist interlocutors. His answer is puzzling: “What did Mill get wrong here? Disagreement requires a shared set of presuppositions about the world.” The passage is puzzling given Stanley’s background in philosophy because it seems to suggest that successful communication (including disagreement) requires that we have the same presuppositions, or as philosophers say, the same common ground. It suggests a view of communication in which we share a stable background, and trade claims within that background. But this doesn’t square with how philosophers of language think about communication — including Stanley’s own dissertation advisor, Robert Stalnaker, who argued that a big part of communication involves updating the common ground, or shared presuppositions. Indeed, more recent work has suggested that updating the common ground is the primary point of communication. If we didn’t have a different “set of presuppositions” there would be nothing for us to talk about.

Stanley is also convinced that in our current context, rational deliberation has no hope against propaganda that tugs at our fears and emotions. As he puts it, “attempting to counter such rhetoric with reason is akin to using a pamphlet against a pistol,” an interesting inversion of Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s adage that the pen is mightier than the sword.

But Stanley is not explicit about what he wants to happen here. Does he want Charlie Hebdo to be censored? Or just “deplatformed?” He leaves it to us to connect the dots, but whatever the mechanism, he’s clearly calling for radical restrictions on free speech. To defend us from totalitarianism. The irony is obvious.

Among the problems with Stanley’s attraction to left authoritarianism is that it wastes an opportunity to get at the real issue with fascism and perhaps enlist conservatives in the cause of fighting it, since guess what? Traditionally, conservatives have taken issue with fascism. That’s because fascism isn’t merely or mostly or even essentially about patriarchy and mythologizing older, agrarian eras. Fascism is also about trashing traditional institutions and consolidating power under a single authority – both things that conservatives tend to have a problem with. But why appeal to conservative hearts and minds when claiming their ideology is the fast train to fascism is a better applause line?

As I was writing this review, John Oliver devoted an episode of his satirical show “Last Week Tonight” to the recent rise of totalitarian governments around the world. Oliver actually had a credible three-point analysis of their common strategies, which involve projecting strength, demonizing enemies, and dismantling institutions – for example legal institutions. Unlike Stanley, Oliver also had a solution, which was a call to vigilance in protecting our democratic institutions.

Oliver’s insight, I take it, was that it is not the valence (left vs right) of totalitarianism that provides the clue to how it arose and how it works. It was rather the strategies for consolidating power under one individual. This takes us to the heart of the problem with Stanley’s book: he mistakes patriarchy, nostalgia for a mythological past, etc. as being the causes of fascism, when they’re at best unreliable clues to the valence of a totalitarian movement.

But there was a crucial point that Oliver, like Stanley, failed to emphasize. The appeal of despotism (of any valence) typically arises in times of crisis – typically a financial crisis or a governmental corruption crisis – when people come to realize that traditional institutions have failed them. People become desperate, and they seek answers outside of democratic institutions.

This naturally raises a question: What leads to this particular moment of global desperation? Stanley seems to think the crisis is manufactured by fascism itself (“corruption” is nothing but a slogan, it seems) rather than decades of neoliberal economics and foreign policy – policy driven not just by conservatives but by Democrats like Hillary Clinton in her role as Secretary of State. When we witness a rapacious foreign policy that bankrupts and destabilizes nations around the world, we set off a chain reaction of debt, and poverty, and migration, and more debt and more despair, and soon the problem is not contained in the subjects of the neoliberal empire, but within the empire’s homeland itself. And when corruption is institutionalized (for example in the aftermath of the Citizens United US Supreme Court decision), people rightly turn on those corrupt institutions.

Perhaps the way that fascism comes about is first, by us failing to provide equitable economic conditions, and by us failing to fight corruption, and by us failing to safeguard and protect democratic institutions.

This isn’t the sort of thing one is supposed to say in the age of neoliberal identity politics. Money is no longer considered the root of all evil. The new view is that the economic order is fine, and the real problem is white privilege or patriarchy, or cisgender privilege. No doubt those are problems, but they are wrong in and of themselves, and not because they lead to fascism. They should be addressed because they are wrong. However, it is not enough to focus on those ills while ignoring economic inequity, corporate imperialism, and widespread institutional corruption. Those are the problems that open the doors to fascism and provide opportunities for despots to play on our fears and hidden prejudices. For fundamentally, that is how fascism works.

4 Comments

Excellent review, perhaps especially the discussion of free speech. One question. You write, “[Jefferson] infamously says that those ‘who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people.'”

Why “infamous”?

Thank you very much for this thoughtful and informative article. I disagree with your final conclusion, but that is what reasonable people do from time to time. But not what SJWs do since they are not reasonable or honest, and they lack even a shred of intellectual integrity. In pointing out the flaws in Stanley’s argument concerning the equivalence of fascism and conservatism, an argument which seems to be intentionally false on his part, you also highlight the danger of SJWs themselves; their reliance on the irrational emotionally driven accusation against anyone who varies in the smallest way from their dogmatic religion of identity politics. I suspect you are going to be targeted by swarms of them decrying your betrayal. You can no longer be treated as an Ally but an Enemy!

I too found Stanley’s attempts to equate our run-of-the-mill conservatism to some kind of proto-fascist conspiracy mongering fatuous and laughable. In the pursuit of absolute power, any “flavor” (or “valence” as you say) of posturing and pandering is just as likely to be seen as any other. Those used in the past may have been effective in their time and place, but that is no indication of their utility in the future. Your analysis was quite clarifying for me, thank you. I also particularly like your summation. You counter Stanley’s feverish propaganda attack on conservatism with perfect moral judo. It isn’t these supposed “symptoms” in our discourse which predict the disease, but rather demagogues exploiting the moral disease itself which leads to totalitarianism. Brilliant repost.

Surely a hostility to high levels of immigration is central to the message and attraction of Trump, Le Pen, Tommy Robinson and Eastern European populists. They resent those immigrants influencing their politics and way of life – and in many cases being better off than them.