By ANNIE WYMAN

What was storytelling for John Berger? In some ways, it was just exactly what you or I might guess it to be: plots, characters, ordered carefully, truthfully and movingly into narrative. But in other ways, it was a mystical, almost metaphysical act. And Berger called himself a storyteller above all else, and so I think it is worthwhile, if we’re re-evaluating his work, to ask what that means. I’m not looking for a definition. Rather, I’m attempting to understand storytelling — a story — as a sort of shape. If you’ve ever watched clothes spin in a dryer, you’ll know the specific, dynamic form they make because of the spin of the drum and the heat. That seems like the right simile: for Berger, storytelling was an activity, a process — but also a set of forces that are equivalent to or generate an atmosphere, a structure. So that’s my project. We’ll see how it goes.

What was storytelling for John Berger? In some ways, it was just exactly what you or I might guess it to be: plots, characters, ordered carefully, truthfully and movingly into narrative. But in other ways, it was a mystical, almost metaphysical act. And Berger called himself a storyteller above all else, and so I think it is worthwhile, if we’re re-evaluating his work, to ask what that means. I’m not looking for a definition. Rather, I’m attempting to understand storytelling — a story — as a sort of shape. If you’ve ever watched clothes spin in a dryer, you’ll know the specific, dynamic form they make because of the spin of the drum and the heat. That seems like the right simile: for Berger, storytelling was an activity, a process — but also a set of forces that are equivalent to or generate an atmosphere, a structure. So that’s my project. We’ll see how it goes.

I want to start simply and avoid our conventional definitions. What is a story? And what does it mean to tell one? I think in fact for Berger telling a story could be something as simple as arranging a stone on a beach, making a mark on a page, or the crossing of a border — or the emergence of almost anything out of nothing, or any estrangement of the world into form — all five of these things he took to be somewhat the same. A story is a passage, as drawing is a passage, set in time:

… another way of putting it would be to say that each mark you make on the paper is a stepping-stone from which you proceed to the next, until you have crossed your subject as though it were a river, have put it behind you. (“The Basis of All Painting and Sculpture is Drawing”)

And there are other simple distinctions to be made. There is, for instance, that much-quoted line from the spicy essay “Art and Property Now”: “The truth is that a painting or a sculpture is a significant form of property — in a sense in which a story, a song, a poem is not.” Of course, we do treat certain stories, certain songs, certain poems as property, but Berger’s point still holds. Stories hold whatever is inside them outside of commodification, outside of markets (if certainly not outside of exchange).

The uncommodifiability of a story is produced by a storyteller in and through “his living immediacy,” to borrow a phrase from Benjamin. The storyteller for Berger as for Benjamin is someone who has come from far away, as Berger once told Susan Sontag, on the 1983 television series Voices — again invoking passage or journey, a crossing of a distance and of the collectivity it creates:

If I think of somebody telling a story, I see a group of people huddled together,

and around them, a vast space, quite frightening. Maybe they are huddled against a wall. Maybe they’re around a fire. And somewhere, for me, in the very idea of storytelling, there is something to do with shelter. The shelter perhaps of the voyager, the traveler, who has come home, who has lived to tell the story. Or the soldier who has come back, who has survived. So there is this almost physical sense of habitation, where the story represents a kind of habitation, a kind of home. But then, inside the story, there is another kind of shelter. Because what the story narrates and tells is sheltered from oblivion, forgetfulness, and daily indifference.

Berger claims to have become a storyteller during World War II, when he helped soldiers write home from the war, sometimes embellishing their stories in return for protection or favors. But it doesn’t quite tell us what abides within a story. Or who. What makes narrative? Why move from one mark on the page to another? In the post-9/11 essay collection Hold Everything Dear, Berger writes:

Desire, when reciprocal, is a plot, hatched by two, in the face of, or in defiance of, all the other plots which determine the world. It is a conspiracy of two (230).

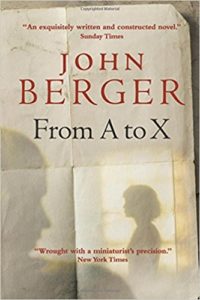

“Conspiracies of two” is a helpful phrase: we could say that it describes many a Bergerian story. This is the plot of Lilac and Flag, the last novel of Berger’s Into Their Labours trilogy, of From A to X, and of G., Berger’s first novel.

Desire, love, mutual human and humane recognition structure everything Berger wrote. (We can see this even in the art criticism: there are always two (or more) historical actors — the painter, who preserves in the intensity of her figuration, her ingenious working of material, the accessible essence of a historical moment — and the viewer of the painting, who accesses that moment in and through her own historical specificity.) For Berger, all was desire, closeness, the libidinous encounter between ourselves and others: “the paths they make toward us and how far we open towards them,” as the poet Gareth Evans writes in “Hold Everything Dear,” a poem composed for Berger and from which he took his own urgent, indeed imperative title.

For one cannot read Berger — in any of his books — and not understand that atomization and suffering were the world’s truths, the darkness in which we meet, and the force behind our need to embrace one another. In “To Take Paper, To Draw,” he writes:

I see a red wash and sanguine drawing by Goya of a woman in prison. She is chained by her ankles to the wall. Her shoes have holes in them. She lies on her side. Her skirt is pulled up above her knees. She bends her arm over her face and eyes so she need not see where she is. The drawn age is like a stain on the stone floor on which she is lying. And it is indelible.

There is no bringing together here, no setting of a scene. Nor is there any questioning of the visible. The drawing simply declares: I saw this. Historic past tense.

Whatever else it might be, a story is a communication of pain, of injustice, of pleasure — of human experience. I think the word communication is better than the word “record” or “document,” since the story exists in the present tense, even when it contains past events. This is the form of time he takes from historical materialism: “another sense of time,” Berger called it, “which could accommodate both the long term (centuries) and the urgent (half-past two tomorrow)”. This is the sense of time of the historical materialist but also, in older western conceptions, the time of all art: its exceptional, infinitely porous present.

In their connection of aesthetics and politics, Berger’s stories — which amount to all the texts he wrote — are secretly addressed both to his now and to our future. The stories he tells of migrant workers to forefend their impending extinction; the stories he tells of Palestinians, to forefend their dislocation and erasure. This is how stories sue for justice — not merely by an act of witnessing or documentation but by an address outside of this world and time.

Story-time (the time within a story) is not linear. The living and the dead meet as listeners felt to be there, the more intimate the story becomes to each listener. Stories are one way of sharing the belief that justice is imminent. And for such a belief, children, women and men will fight at a given moment with astounding ferocity. This is why tyrants fear storytelling: all stories somehow refer to the story of their fall.

Herein lies the obvious relevance of storytelling today, of a renewed commitment to the humane work for which we can take Berger as a symbol and a guide.

And, too, we can pick up the idea that ways of telling are ways of seeing, ways of sensing: drawing is writing. Berger addresses the painter Liane Birnberg:

Your paintings are wordless stories. The term may sound strange. How can there be any narrative without words? … as a storyteller, I know that new stories begin wordlessly. Their shape, their colour, their smell, their temperature, their short hairs, their eyes, and above all their fingers with which they touch are there, distinct and unique, before a single word has been found. Words finish stories rather than engender them.

The sensuous — often the sensual — and the sensorial precede language. Not only did Berger’s criticism often tell stories, I think we could say that Berger thought of whatever was uncommodifiable about art as its story, even or especially when that story could not be put into words. It kept the past alive within it, for any present or future person to access as a reservoir of not just of aesthetic but moral and social and revolutionary possibility.

Perhaps we should think of each act of storytelling as a kind of sedimentation, each of his texts in the sense of textile, of canvas or linen. Here is Berger on Birnberg again:

You show us how we wear the past, as if it were a garment, or, more accurately, how the present wears the past next to its skin. You, the painter, follow where those whispers lead, and if we follow you, we too begin to discover the space, the topography of the past, a topography wherein distance is replaced by layers which are more or less transparent, where there is no horizon, only Origin, where roads and paths are repeatedly folded, like linen, to become palimpsests. Your paintings are wordless stories.

A story is a space to be within, together, a whispering, across times and spaces, a passionate line reached from living to dead — but it also the shape of a pocket, a container for experience, an intimate home for the body. In that way, it is less like whatever spins in the dryer than what comes out of it, freshly washed — washed even in ashes, as the peasants of the Haute Savoie do their washing — an empty page, an empty canvas, resilient, receptive: “I am a storyteller because I listen,” Berger said. And why listen? As he wrote on the first page of From A to X, “Life is a story being told now.”

***

Annie Julia Wyman is a doctoral candidate in the English Department at Harvard. Her nonfiction and essays have appeared in n+1, the New Yorker, the Believer, Cabinet, and elsewhere.

No Comments