By BRUCE ROBBINS

This essay was first delivered as a talk on a panel called “New Classroom Boundaries” at the Modern Language Association convention in Philadelphia in January. Our mandate was to talk about language that sets boundaries for classroom discussion and therefore polices transgressive speech. My fellow panelists mainly talked about sexuality. But it seemed to me that the use of the term anti-Semitism was equally relevant, especially as concerns discussions of the Middle East. I began with an anecdote that doesn’t happen in a classroom and that doesn’t have any anti-Semitism in it. Here is the anecdote.

This essay was first delivered as a talk on a panel called “New Classroom Boundaries” at the Modern Language Association convention in Philadelphia in January. Our mandate was to talk about language that sets boundaries for classroom discussion and therefore polices transgressive speech. My fellow panelists mainly talked about sexuality. But it seemed to me that the use of the term anti-Semitism was equally relevant, especially as concerns discussions of the Middle East. I began with an anecdote that doesn’t happen in a classroom and that doesn’t have any anti-Semitism in it. Here is the anecdote.

Once upon a time, in a university not so far away from here, I was up for a promotion, and I didn’t get it, and I was told afterwards that a senior colleague had voted against my promotion on the grounds that I supposedly failed all my students who were Zionists. After some negotiations by the person who had passed on this news, I ended up having lunch with the senior colleague who had voted against my promotion. I was able to inform him, as our meal progressed, that it could not possibly be true that I failed my students who were Zionists because up to that point I had not failed any students of any political persuasion. And, after some gentle digging, I was able to hear with my own ears the evidence on the basis of which he had spoken up against my promotion. That evidence was this: one Jewish student, who had of course not been failed in my class and in fact had not taken my class, had said that for him, knowing I held opinions critical of Israel, whether or not I ever discussed those opinions in class, made him feel (I quote) “uncomfortable.”

The immediate relevance of this story to the subject of fraught classroom situations is not as direct as I would like, but as I see it, no excuse for re-telling this story can be neglected. And there is of course some relevance. The story raises questions about student discomfort in the classroom and about the asininity of their elders, whether in the faculty or (more often) in the administration, who choose to invest that discomfort with high seriousness and treat it as actionable.

There is a general point here that doesn’t need any underlining about the corporate university increasingly coming to define students as entitled consumers. There is a point for the Left, also familiar enough by now, but as it happens the point I had in mind when I chose my title: when students can stop critics of Israel in their tracks and even sometimes get them fired or de-hired merely by crying “anti-Semitism,” when (in other words) Zionism has managed to find shelter for itself under the umbrella of multiculturalism, it’s time for those of us who care about the substance of multiculturalism to think about finding ourselves another umbrella. And there is a point for all of us who are doing our best, little by little, to digest the consequences of November 8th.

After the presidential campaign, we have before us the indelible and now nightmarishly recurring image of the “thin-skinned bully.” That image should be of some theoretical use.

In casual conversation, I have heard racism described not as bigotry, which is assumed to be universal, but as bigotry plus power, specifically the power to make others suffer from the bigotry and in some way to benefit from it yourself. The assumption is that you cannot be racist if you are also being made to suffer from the racism of others. This position seems to me extremely naïve in its assumption about where power is located. It takes for granted that power is located in one place, and stays put there, and cannot be turned around or upside down, for example by means of complaints about racism, real or imagined. The students at the University of Illinois Urbana/Champaign who complained about Steven Salaita’s tweets during the Israeli bombardment of Gaza in 2014 and thus helped the university “de-hire” him were exercising a measurable amount of power in the act of expressing their sensitivity to imagined racial slights. That’s how it works.

Let us therefore find a silver lining in the very dark and ominous cloud. Let us take advantage of having had the image of the thin-skinned bully so forcibly impressed on us in 2016 and let it serve as a reminder of how often hyper-sensitivity and bullying can go together.

You may not need a refresher course in this topic, but I remind you that a great deal of thin-skinned bullying has been going on recently in supposed response to anti-Semitism, much of it seeking the sanction of law. In December the New York Times ran an article by Kenneth Stern entitled “Will Campus Criticism of Israel Violate Federal Law?” The federal law Stern is referring to here is the Anti-Semitism Awareness Act of 2016, a speech code for schools and colleges that’s presented as common-sense protection against bigotry. It was unanimously passed by the Senate, while the House Judiciary Committee put off consideration until 2017. Stern, the former director on anti-Semitism for the American Jewish Committee, is also the lead author of the definition of anti-Semitism on which this legislation is based. That definition, he says, “contains examples related to criticism of Israel,” he writes, “including applying double standards by demanding it behave in ways not expected of other democratic countries, or denying Jews the right of self-determination by claiming that the existence of Israel is a racist endeavor.” I myself disagree with both of these points, but I applaud Stern when he says that, the political situation on campus and off being what it is, he has testified to the House Judiciary Committee that (I quote) the bill “should not be considered in any form.” I hope other Jewish leaders will also be standing up, under the new administration, and taking similar stands.

On December 28th, David Feldman had an article in The Guardian about the new definition of anti-Semitism adopted by the Conservative government of Theresa May and quickly agreed to by Labour. The definition comes from an inter-governmental body, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. Its key passage goes like this: “Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred towards Jews.” As Feldman comments with some understatement, “This is bewilderingly imprecise.” He goes on: “The text also carries dangers. It trails a list of 11 examples. Seven deal with criticism of Israel. Some of the points are sensible, some are not. Crucially,” Feldman says, “there is a danger that the overall effect will place the onus on Israel’s critics to demonstrate they are not antisemitic.” You begin to recognize a pattern.

And to bring things home, in early January David Palumbo-Liu had a piece in the Huffington Post about threats of a lawsuit against the MLA from a group with the grand name, the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law. (Do they think there are human rights that are not under law?) The threat aimed at a resolution, subsequently voted down by the MLA Delegate assembly, to boycott Israeli academic institutions. For what it’s worth—I would like to think this might be a sign of withdrawal from a position coming to be recognized as indefensible—the civil rights group’s letter of warning to the MLA does not dwell on anti-Semitism but merely insists the resolution would sow divisiveness among its membership and in this and other ways carry it beyond its mission. (What is threatened is an Ultra vires lawsuit, a means by which shareholders in a corporation could sue boards of directors for allegedly taking the company in a direction that went beyond its original mission.) Palumbo-Liu’s account of the history of MLA resolutions, for example with regard to Jewish scholars in the Soviet Union, answers this charge to my own full satisfaction. On the point of “divisiveness,” he recalls Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” where King voiced his great disappointment in those who prefer “a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” Palumbo-Liu concludes by making an explicit reference to the then incoming US administration: “The rich and powerful are prime users of ‘lawfare’—they can mount lawsuits to intimidate others from even thinking about crossing the line. Our new President excels in this—for instance, threatening to sue newspapers for libel if they depict him or his policies unfavorably, when in actuality they may be just doing their job. Organizations like the MLA might well decide it is more prudent to avoid even a lawsuit it could win, preferring the absence of legal ‘tension’ in the form of lawyer’s fees. The question is whether justice, in the form of staying true to its mission, is worth it.” The new president’s expressions of disrespect for the law and its so-called judges, disheartening as they have been, are not sufficient reason to let down our guard.

My original plan for this talk, not very well worked out at the moment when titles were demanded but certainly there in my mind, was to cast some doubt on the ways the charge of anti-Semitism has been used on campus to stifle criticism of Israeli policies. I hope I’ve done that. But among the more significant things the election has changed and is continuing to change, it also made a change in what I wanted to say. The assumption I was making was that in the context of American universities, the anti-Semite is a convenient fiction, and most anti-Semitism is more or less phantasmatic. What we’ve seen with Trump’s election, of course, is a certain amount of reptilian anti-Semitic life coming out from under its rocks and leaving marks on people’s doors. This means that classroom conversations in the coming years can’t afford to assume the reptiles aren’t there.

On the brighter side, it also means a renewed opportunity to think of anti-Semitism and other forms of racism as historical. I would argue, knowing full well that many will not agree, that getting the lizards to hide under their rocks was a significant step in a desirable direction. It had historical causes—where anti-Semitism is concerned, the obvious example is sympathy for victims of the Holocaust—and it can be described as a historical event. If you will permit me to push my metaphor beyond my zoological knowledge, I would add that lizards do not thrive under rocks. If they are afraid to come out from under those rocks, they cannot reproduce themselves or spread with the same ease. Dov Waxman, writing in his book Trouble in the Tribe: The American Jewish Conflict Over Israel, remarks that there has been “a steady decrease in anti-Semitism in American society since the end of World War II . . . Despite lingering fears of anti-Semitism, by and large, American Jews feel secure in the United States.” Why then the extraordinary Jewish-American support for Israel that claims to base itself on anti-Semitism? American Jews, Waxman writes, “are more worried about losing their collective identity than their lives. Assimilation is a bigger problem than anti-Semitism. It is the open embrace of gentile American society, not its hostility, that poses by far the greatest challenge to the American Jewish community. Supporting Israel helps in this respect, as it has become a crucial means of sustaining and expressing Jewish identity.” For American Jews like me, Israel can function as a surrogate. We may not experience anti-Semitism ourselves, but as long as we convince ourselves that Israel experiences anti-Semitism, we need not even notice how at home we have become (for better or worse) in American society or, for that matter, how Israel’s daily misconduct violates our values even more dramatically, in fact much more dramatically, than America does.

Among the assumptions I’m making here that may seem questionable, one has to do with what might be called my patriotism: the idea, say, that there is a qualitative difference between American racism, which is unofficial, and Israeli apartheid, which is not. Another has to do with what I think racism is. In my experience, assumptions about what racism is are not talked about in the classroom; rather, they set the boundaries of what can be talked about, and how. It’s those boundaries that would restrict conversation about how Israel is benefitting from protection it does not deserve. To be more precise: I’m not convinced that the replacement of fear of anti-Semitism by fear of assimilation, as Waxman lays it out, would be accepted by students as marking a decrease of anti-Semitism or, therefore, as one example of the more general historical phenomenon of a decrease in racism. Many students would I think want to say that assimilation is simply racism under another form. The underlying premise would be that racism never can decrease, but can only change its form—in effect, that racism is not a historical phenomenon in the sense of waxing and waning along with historical conditions. In my opinion, that’s where the battle lies: getting people to think that the conditions that produce racism are not to be found in people’s hearts or subconsciouses, but out in the world, where very little is absolute.

It is to be expected that there will be opposition to the project of de-absolutizing racism. Young people are not alone in preferring moral absolutes which seem to banish divisiveness, like “racism is bad.” To see anti-Semitism and other forms of racism as historical means that the moral imperatives that accompany racism are not absolutes; they also wax and wane according to circumstance. The extraordinary tenacity of anti-Black racism in the United States will give pause, as I think it should, but I don’t think it changes the principle. It seems self-evident to me, for example, and the data back this up, that recurrent spikes in anti-Semitism can be correlated with recurrent Israeli bombings of Gaza. If Israel were to stop bombing Gaza, to withdraw its siege of Gaza, to withdraw from the Occupied Territories of the West Bank, to offer equal rights to its Palestinian citizens, and so on, and if the American Jewish community were to accelerate its visible but too slow shift toward the acceptance of the need for all these reforms, a decrease in anti-Semitism would be one sure benefit, though by no means the most significant. That result depends in part on what is said in classrooms.

I will conclude with a story that does happen in the classroom and does have anti-Semitism in it.

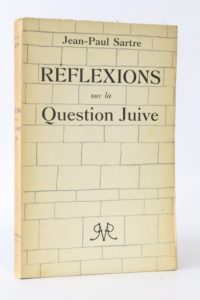

One of the rare occasions on which I showed pedagogical courage came during a classroom discussion of Sartre’s Réflexions sur la question juive, translated as Anti-Semite and Jew. I was teaching this text in a course that began with Hegel’s famous Lord/Bondsman story of the birth of self-consciousness, from the 4th chapter of the Phenomenology, and then marched forward through Marx and Nietzsche, Kojeve and Lacan, Sartre and de Beauvoir, Fanon and Levinas, Butler and Zizek, showing how everybody had found what they wanted to say by re-telling the same story and, of course, varying it. Sartre used Hegel, as read through Kojeve, to pose the question of where anti-Semitism comes from. In order to make people see how important the question was, I felt I had to ask the students what they thought racism was. And that led me to ask (it’s also one of Sartre’s questions) what might make anti-Semitism go away. Students were wary—they could sense, correctly, that this was a something like a trick question: it engaged with the rules of classroom discussion themselves, in particular the deference to the sensibilities of others by which (literature being a vehicle for empathy) literature classrooms are defined. To admit that anything could ever make racism go away seemed to imply that the rules of classroom discussion were not themselves eternal and that the moral imperatives behind them were not moral absolutes, good for all times and places. I can’t say I remember exactly how the classroom discussion went, but I think it’s a good thing that it happened.

***

Bruce Robbins is Old Dominion Foundation Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University. His book The Beneficiary is forthcoming from Duke University Press.

No Comments