The Spitfire Bar on al-Bursa al-Qadima Street, or Rue de l’Ancienne Bourse, in Alexandria, which sported so many watering holes during World War II, that the Allied troops dubbed it “Beer Alley.” Perhaps the Spitfire was one of the haunts they hankered after, out in the Western desert, when they promised themselves an Ice Cold in Alex, this being the title of a war film directed by J. Lee Thompson (1958). Photograph, taken on August 19, 2018, courtesy of Reda Farag.

In early January 2014, some three months after the publication of my Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism: An Archive, a British professor e-mailed me to say he was reviewing the book and had some queries. It was only when he had done an online search that he established that I am Alexandrian: why had I not mentioned this in the book? Would I consider adding it to the biographical note on the author in a later edition? And what was my background, ethnically, among other things?

“Yes, I am Alexandrian born and bred,” I wrote back. “I must admit that my academic socialization (all of which took place in Egypt, including the MA–it was only the PhD that I obtained in the US) was such–perhaps quite old-fashioned–that referring to oneself in one’s own writing was somewhat frowned upon. It took me years to be able to replace ‘one’ by ‘I.’’ “But,” I continued, “there’s also a reticence on account of not wanting to come across as staking a claim to the subject on account of being a ‘native’ Alexandrian or playing identity politics.”

“On the other hand,” I added,

I fully see your point about making one’s positionality [my word, not my correspondent’s] visible. What I could muster in that direction was the first words of the Acknowledgements, (“From Alexandria, where it all began [, this project has taken me to several cities]”) and the first endnote where I talk about having been writing on different aspects of the subject since the early 1990s; I also put a number of my older texts (MA thesis [on Alexandria, 1992] and academic and newspaper articles chiefly published in the Ahram Weekly where I worked for years as Culture editor) on the bibliography for documentation.[1]

I begin with this anecdote of formation as a necessary preface to the genre of essay I have been invited to write here: a response to May Hawas’ “How Not to Write on Cosmopolitan Alexandria” published in Politics/Letters on May 28 of this year and her comments on my work (hereafter “HNWCA”).

Only part of the present essay, though, is a corrective to her statements that, in my view, altogether misrepresent Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism. What animates me more is to rectify what I consider to be her misinformed and misinforming statements about Alexandria, which betray utter disregard for the local production of knowledge and citizen agency.

It is my scholarly and ethical duty towards readers and towards Alexandria to set the record straight about the city’s recent history, its civil society and cultural initiatives, to which I devote the last two sections of the essay. Let me reiterate: it is not on the grounds of my birthplace but on the strength of my involvement in Alexandria and, for close to three decades now, extensive writing about the city, that I undertake this task.

“The affliction of our alley is forgetting”: be the alley Egypt or the human condition, surely the Mahfouzian adage should prod us to remember and reflect with insight and integrity–and an eye towards a better future.[2]

Literarily speaking

What argument did Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism put forward? Focusing on the discourse on Alexandria’s cosmopolitanism in the modern period, the book argued:

Well into the nineteenth century this city and that concept had not been so firmly yoked…. It is no coincidence that what is referred to as Alexandria’s cosmopolitan period–roughly from the 1860s or 1880s to the 1950s or early 1960s–overlaps precisely with growing European intervention in the country, the British occupation and hence direct colonial control that ends in the 1950s. To argue that it is as underwritten by an accelerated colonial modernity that “Alexandrian cosmopolitanism” comes into being is by no means to suggest that cosmopolitan practices or different modes of cosmopolitanism had been hitherto absent from Alexandria or, for that matter, Egypt. It is, rather, to identify and critique the dominant account of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism as a discourse that, beholden to colonial conditions, drew on a site-specific archive to configure itself.[3]

If modern Alexandrian cosmopolitanism was a Eurocentric account of the city complicit with colonialism, it was largely Hellenizing. That is, it represented modern Alexandria as a re-creation of the city in its “Golden Age,” the Hellenistic period. Simply put, the narrative placed all things European/Greek under the sign of cosmopolitanism and all things Egyptian/Arab under the sign of decline.

Genealogically, Alexander the Great, the world-conquering founder of the city, had of course been variously associated with cosmopolitanism. Not the least of these associations is Alexander’s fabled encounter with Diogenes the Cynic, the presumed originator of the term “cosmopolite”–that goes from there into Stoic thought. The notion of cosmopolis–of which Rome is considered to be the ultimate expression–attached itself to Hellenistic Alexandria from its foundation myths onwards. Over and above ancient Alexandria’s ethnic diversity and strategic geographic position, “the city’s bid to universality” was secured by “its monuments–such as the Pharos Lighthouse and Alexander’s mausoleum…–and above all its institutions, primarily the library and the Mouseion” (AC 17).

It is precisely the preeminence of Hellenistic Alexandria, its myths and icons that are appealed to in the process of constructing modern Alexandria-as-cosmopolis. I tackle the way disciplines such as historiography and archaeology enshrined that discourse of cosmopolitanism by producing an “invented tradition,” to borrow Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger’s phrase.[4] The “matrix that upheld the collective presence of these communities was that quasi-colonial, often Hellenizing cosmopolitanism.” It thus secured “for the colonies of modern Alexandria a European genealogy of cosmopolitanism, [which] in turn conferred further legitimacy on the quasi-colonial conditions and institutions that supported their presence” (AC 22, 23).

The standard historical account of Alexandria goes on to bracket roughly twelve centuries–all the way from the Arab conquest to the arrival of Napoleon–as a moment of decline and fall. And more recent writings about the city “fold… over that account [of Arabo-Islamic decline] on post-Suez Alexandria by depicting it as likewise a city fallen from cosmopolitan grace” (AC 45). “Museums, and the museumizing imagination [being] profoundly political,” as Benedict Anderson has taught us, we cannot but note a species of archaeological irredentism in the naming–and accompanying curatorial gestures–of the city’s Graeco-Roman Museum, the first three directors of which were Italian.[5]

But what fascinated me most as a comparatist was this: the hitherto unchallenged contributions of largely Anglophone (and certainly some Francophone) literary and cultural criticism to this discourse of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism. Traditional processes of canon formation have been critiqued for decades–and yet, these processes, I found, survived in the context of much, if not all, scholarship on Alexandria, blissfully unimpinged upon. In that “lit. crit.” time-capsule I located what I called the “Alexandrian canon”: the triumvirate of C.P. Cavafy, E.M. Forster, and Lawrence Durrell.

It is not solely the exclusion of texts in other languages–not least Arabic–from the canon that is at stake. What it more, the standard “readings draw from the literary triumvirate a Eurocentric cosmopolitanism complicit with the colonial conception of the city–which the critics by no means shun–by dint of overlooking certain texts, occluding resistances in others, and disregarding genre expectations in given instances” (AC 43).

Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism, then, read “against the grain of received critical wisdom” (AC 3). It devoted a chapter to each member of the triumvirate, and then a final chapter to Bernard de Zogheb (1924-99). A word about de Zogheb, since he had been, until my work on him, a virtually unknown Alexandrian Syro-Lebanese artist and librettist whom I had the pleasure of interviewing for a profile I published in Al-Ahram Weekly in 1996. There were waves of Syro-Lebanese migration into Egypt in the modern period, particularly in the second half of the nineteenth century on account of sectarian incidents in the Levant; de Zogheb’s family, however, seems to have settled in the country in the early nineteenth century, an ancestor apparently having worked with the French during the Napoleonic occupation (AC 227). There, like other members of the “Levantine” elite, they prospered, acquired the title of count from the King of Sardinia, and dabbled in the arts, particularly theatre. De Zogheb wrote at least ten libretti, only one of which has been published thanks to the patronage of James Merrill; I collected copies of these manuscripts, as well as of de Zogheb’s letters, diaries, scrapbooks, and recordings of his operettas. The libretti, set to pop tunes, are written in a pidginized, macaronic Italian–dovetailing English, Arabic, French and Greek–in a Lingua Franca-like experimentation with Alexandria’s polyglot hybridity: code-switching, portmanteau words, calque translations, triple puns, etc. The operettas camp up the tropes of shifty derivativeness and artifice that the West stereotypically associates with the figure of the “Levantine” and spoof high canonical forms. They do so to perform a two-pronged process of self-legitimization of queerness and an elite Alexandrian-Levantinism. The libretti’s subjects include Cavafy, the Brontë sisters, and Lord Byron, as well as an assortment of fictional characters such as a hysterical Levantina who has an altercation with a Mme Lavabo (Madame Washbasin), an impoverished Russian aristocrat, in a Parisian art nouveau ladies bathroom.

As for the triumvirate, my claim is that they are far from consonant with each other on a Eurocentric vision of Alexandria’s cosmopolitanism. Cavafy, in his capacity of a modern Alexandrian Greek whose poetry adduced the Hellenistic city, has long since been pressed into service as the figurehead of the dominant account of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism. What intrigued me, too, was that most of the Anglophone criticism of Cavafy drew out of his corpus the antithesis of cosmopolitanism: a binary of Greek (read: European) versus barbarian (read: Egyptian/Arab/Islamic), despite the fact that the meaning of “barbarian” shifts historically. I therefore “put this received critical wisdom to the test by posing the question what constitutes ‘Greek’ and ‘barbarian’ in his work and how entrenched that binary is” (AC 54). This I did by probing the workings of that binary in relation to a range of other categories in his text: the Hellenophones, the Philhellenes and the Egyptiotes. What I found was that “in almost all the categories, there is some evidence–to a greater or lesser degree–of binarism at work; simultaneously, the corpus of prose and poetry is polyvalent,” permeable, antiessentialist, revealing “a continuum of shifting identities and an empathy that bespeaks a diasporic Greek’s sensibility” (AC 60).

Orientalism impinged on Cavafy’s texts, no doubt, as I show; but his empathy is also fully in evidence, for example, in one of his published poems, “For Ammonis, Who Died at 29, in 610.” The date in the title sets the poem in the very last years of Byzantine rule over Egypt, which were followed by the Persian occupation and Byzantine retaking, and then the Arab conquest. The name of the dead Alexandrian poet Ammonis furnishes an ethnicity: the Copts. A group of young men are pleading with an Egyptian hellenophone poet, Raphael, to infuse his epitaph with homoerotic allusions to Ammonis’ beauty. I detect in the urgent appeals to Raphael not only the trauma of mourning but another trauma, a linguistic, cultural one, as the poem looks back on a millennium in which Greek was the literary language and looks towards the Arab conquest. The young men do not know Greek, hence would fit one construction of the barbarian. And yet Cavafy “places himself,” empathically, “in a continuum, via the figure of the Hellenophone (Raphael), with the figure of the barbarian” by having the speakers twice refer to his own language as “foreign”: “our sorrow and love are passing into foreign speech / pour out your Egyptian feeling into the foreign speech” (AC 93). In the desired epitaph, as the prescription in coda has it, “both the rhythm and each phrase declare / an Alexandrian is writing for an Alexandrian.”: in my reading, the poem thus is “about the possibility of a transculturated, emphatically hyphenated Egyptian-Greek textuality” (AC 87; emphasis added).[6]

Another fascinating poem is “27 June 1906, 2 P.M,” one of the texts in Cavafy’s poetic corpus that he kept in a “hidden” category–neither rejected nor published per his idiosyncratic way of disseminating his work. The date in the title of this poem (written in 1908) is the hanging of four men from a village in the Delta, Dinshiwai, in a colossal instance of British colonial injustice that was to bring to a head resentment of the occupiers, and became the subject of a nationalist media campaign and of poems, folk ballads and songs. The poem opens with “When the Christians brought him out to hang him, / the seventeen-year-old, the innocent boy, / his mother, who was near the gallows / crawled and beat herself on the scattered earth,” and by the end of it, the “mother-martyr” is no longer lamenting her son’s seventeen years: “‘Only seventeen days’ was her dirge / ‘only seventeen days, my joy, my pride with you, my boy.’”[7] It is hardly surprising that the poem barely elicited Anglophone critical commentary. What to make of the loaded marker “Christians” in the first verse? Far from being Orientalist, it reads as “an assertion of empathy… reminiscent of that at work in Ammonis’s friends referring to the Greek language as ‘foreign speech’… here an empathy with villagers in the Delta against Europeans/the British.” Both poems “are made into vehicles for specifically indigenous Egyptian (the fellahin, in this case predominantly Muslim [in ‘27 June 1906, 2 P.M’], and the Copts [in ‘For Ammonis’], respectively) mourning” (AC 101, 103-04).

The Egyptian-Greek writer and critic Stratis Tsirkas speculates whether that usage is taken from an Egyptian popular ballad, a suggestion I support by citing one such text that refers to the British as “al-nasara” (the Nazarenes).[8] One of the parts of the Cavafy chapter that I enjoyed writing most, taking off from my discussion of this poem, was Egyptian dialogues (critical, translational, also visual) with Cavafy’s corpus. Indeed, “27 June 1906, 2 P.M” found an affirming afterlife in its Egyptian reception. I agree with the Egyptian critic Raja’ al-Naqqash’s suggestion that “the poem’s reference to ‘Christians’ and the image of the ‘mother-martyr’ are ironical commentary on the behavior of the British in this incident by contrasting it to Christianity’s ethos of forgiveness and mercy” and the civilizing mission (AC 108). I accounted for Cavafy’s decision to keep the poem hidden by comparing his situation, as an employee of the British, to that of his contemporary Egyptian writer Mahmud Tahir Haqqi, author of the novel ‘Adhra’ Dinshiwai (The Virgin of Dinshiwai), who also held a government post and was called in and intimdated by the British. As the Alexandrian artist and poet Ahmed Morsi who translated a selection of Cavafy’s poetic corpus and visually dialogued with them through a series of etchings, observed, this is one of the Alexandrian Greek’s texts that demonstrate that he “‘shared the emotions and passions’” of Egyptians (AC 106).[9]

But what of Durrell? There is the overwhelming purple lushness of The Alexandria Quartet, of course. Incantatory passages aplenty that invoke ethnic heterogeneity–the place names, the Alexandrians’ own names, the chestnut pieces–are strewn over the four volumes, ready for any anthology. “If Alexandria’s cosmopolitanism were merely a matter of its ethnic and religious heterogeneity, then there would be no dearth of evidence to shore up from the Quartet to nominate it as the ur-text of this cultural matrix,” I had written (AC 181). I did attend to the Quartet’s modernism, in particular its experimentation with Freud’s uncanny, as well as his Interpretation of Dreams, in relation to the idea that an individual’s unconscious contains traces of primitive memories and myths (ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny). One thing Durrell located in Alexandria, I suggest, was an ideal space for his fictional “mulling over the connections between psychanalysis and anthropology,” exploiting what he saw as “both a modern city and one that comprises a perceived African primitiveness” (AC 193, 194).

But the possession by the Alexandria archive, the doubling, the menacing quality attributed to the city and its Levantine elite, the ef/feminized hysteria and superstitions that bedevil the characters–all that, in my view, “owes more to the twilight-of-empire moment of the time of narration” in “a belated permutation of colonial discourse” (AC 193, 181). While Durrell set the Quartet in the 1930s and ’40s, let it be recalled that its volumes were published between 1957 and 1960, after Suez, though he had been planning the text earlier. The uncanny heterogeneity is represented as a threat to a “(would-be) sovereign and decidedly male, imperial subject–whether that of the colonial administrator or of the Western writer, Durrell himself having doubled in the two roles” (AC 183). It was “my wager that the text looks forward to, as in tries to conceive of and conjure up, a neocolonial afterlife of older imperial forms. It is in this sense that I reinterpret the Quartet’s much-vaunted cosmopolitanism as a hybridity that the text construes as potentially threatening but also as ultimately amenable to perpetuating the decolonized nation’s dependency” (AC 181). And this at roughly the same time when Frantz Fanon and Kwame Nkrumah were warning against neocolonialism.

How does neocolonialism work in The Alexandria Quartet? How to parse such passages as these: “Alexandria, princess and whore. The royal city and the anus mundi. She would never change so long as the races continued to seethe here like must in a vat; so long as the streets and squares still gushed and spouted with the fermentation of these diverse passions and spites, rages and sudden calms.”[10] The princess and whore, in the immediate, need it be added, is an allusion to Cleopatra. “While never coalescing into a single emblematic figure, the feminization of Alexandria by modern Western writers often draws on the Graeco-Roman archive of the city by alluding to a Cleopatra whom Orientalism would later endow with an odalisque-like quality.” In that chestnut passage from the Quartet, Durrell draws for the feminization on the “two registers, the Hellenistic/Graeco-Roman and the Orientalist” (AC 21). The “princess and whore” has, of course, her incarnation in the Quartet’s Justine, who emblematizes the feminized city. Justine it is who marries the Coptic Nessim, and whose “whoring”– extensive affairs in service of the cause–is all about the conspiracy or “the plot” she and her husband are concocting.

As other critics, too, have noted, the Quartet displays an occasional irony about Orientalism.[11] However, my claim is that the text

ultimately goes on to perform a new gesture in which literature and neocolonial power this time are in collusion, witnessed in Durrell’s concoction of the highly contrived Coptic-Jewish anti-Arab nationalism and pro-Zionist conspiracy. (AC 213)

What is that conspiracy?

One of the key plots in the book, the unfolding of which grafts layers of different motives onto actions hitherto partially understood or altogether misunderstood (alliances, affairs, treacheries, and disappearances), this political scheme of Nessim’s brings Copts and Jews together, hence his marriage to Justine, to prove his credentials to Jewish fellow conspirators. The plot consists in an underground network concerned with smuggling arms into Palestine in an alliance with the Jews there, in hopes that a triumphant Zionism, when it has overthrown the British mandate in Palestine, would work to protect the interests of non-Muslim groups in the region, specifically the Copts, against the perceived hostility of a rising tide of Arab nationalism. (AC 204)

I consider some historical sources, entirely unrelated to the Copts, that Durrell may have drawn on, such as “‘Operation Susannah,’ also known as the ‘Lavon affair,’ [which] unfolded in 1954 when Israeli Military intelligence had a number of Egyptian Jews whom it had recruited as spies conduct terrorist attacks,” including bombing Alexandria’s central post office, several cinemas in Alexandria and Cairo, and other establishments (AC 219).[12] This operation, exposed the same year, was intended to persuade the British that Egypt was unstable, with the hope that that would put an end to their negotiations with the Egyptian government to withdraw their forces from the Suez Canal zone. Whatever the historical provenance of the conspiracy, to which Justine is pivotal,

transposing it to the Copts turns the plot into “an insider job,” which has several consequences in the late 1930s and early to mid-1940s time frame of the Quartet. It forges a fictional division within the region, as it alienates a rooted community by contriving solidarity between it and a movement that sought to establish a new settler colony on Arab lands. (AC 219; emphasis added)

Furthermore, if Justine and Nessim are headed to Switzerland at the end of the text, onto “something bigger this time, international,”[13] as she breathily confides in her friend Clea, then “their pro-Zionist orientation,” their multilingualism, and extensive transnational network, “‘cosmopolitan’ qualifications all… in their case specifically, and in view of their agenda, make for particularly unsavory versions of transnational subjects.” This is why I conclude that the Quartet should be read “in the vein of a cautionary tale, against the grain of the text [as it] effects a smooth, almost slick, transition from twilight-of-empire in the ‘Levantine,’ menacing space of Alexandria to long-distance neocolonialism enabled by exilic, cosmopolitan figures” (AC 224, 225).

Hawas produces a quotation from my book about how the dominant account of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism excludes Egyptians, “who constituted the majority of the city’s population and its labor force,” and pays “insufficient attention to the materiality of Alexandria, in the sense of the actual city and the class dynamics in relation to ethnicity.” Surely, to write about cosmopolitanism–Alexandrian or otherwise–with integrity, necessitates that we read its articulations in relation to class, ethnicity and, as I do in the book, gender and religion.

She goes on to claim that “There follows a mention, again not unique to Halim, about Egypt’s ‘foreigners’ who ‘left’ Egypt in the sixties–though the unquestioned past simple is hers” (“HNWCA,” emphasis added). This, in my view, is an outright distortion of my point in the passage in question. There, I critique the way Alexandria post-1956 is figured

as a city in decline, in this case fallen victim to nationalism, the members of foreign colonies having departed, thus depleting that space of its cosmopolitanism. That these departures occurred under different conditions—the country’s decolonization, the Suez War and sequestrations of assets of British and French subjects, the Egyptianization of the economy, the early 1960s socialist-inspired policies of sequestrations and nationalizations—and unfolded differently for different colonies, being often elective rather than coerced, is rarely noted. Nor is it observed that not all members of European colonies or Alexandrians of mixed origin left. (AC 22; emphasis added)

What the passage actually does is, precisely, to nuance, subtilize and question the reductive narrative of departures.

Hawas claims that “Historical fallacies about Egypt’s political economy of the time also beset these discussions, some of which themselves seem nostalgic of the Nasser period when Egypt seems to have had a louder internationalist bark than it does today” (“HNWCA,” emphasis added). The next statement she makes about my book is therefore all the more astonishing as it misrepresents several issues and betrays an obliviousness to historical fact, to put it mildly:

In Halim’s account, Nasser’s “nationalisation” (because if we call it what it was, that would be judging it too harshly) of assets belonging to the British and French (only the British and the French are mentioned, there’s nothing about the others) is even described as the “Egyptianization” of the economy, because apparently appropriation by a new ruling class is something very different from exploitation in the feudal system. So much for resisting complicit authoritarianism. (“HNWCA,” emphasis added)

First and foremost, anyone who has a modicum of knowledge about Egypt’s modern history will know that “the Egyptianization of the economy” (tamsir al-iqtisad)–far from being my own word choice–is in fact the name of an economic policy under President Gamal Abdel Nasser, as used in his speeches and in legal and public discourse at the time. The tamsir of the Nasser period (the term has a pre-history) is a policy that belongs to the aftermath of Suez when “French, Australian and British enterprises” were sequestrated, the “laws relevant to the Egyptianization [tamsir] of banks, insurance companies and import agencies [being] published on January 15 [1957].” Tamsir and nationalization share some features but are not identical; nationalization, for one thing, is a more far-reaching process that peaks in the quasi-socialist turn of 1961-62. This is why my sentence carefully makes a distinction here, as historians of the period do, something Hawas misses again when she thinks she has caught me in a complicit act of describing nationalization as Egyptianization.[14]

Second, it should be obvious that I was providing historical context; that is, my words are descriptive rather than prescriptive. If a writer half a century from now uses the term privatization to refer to privatization, this would not justify taking her to task as complicit. Parenthetically: Hawas accuses me of not resisting “complicit authoritarianism” tout court (i.e.: this is not complicity with authoritarianism). In the abstract, what would such a creature be complicit with other than itself, and perhaps colonialism/neocolonialism and their underpinnings? But let that not detain us.

Third, even the most cursory bit of research would have established that indeed, prior to Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism and cited in it, my published work had criticized aspects of the Nasser regime, including the socio-economic. I refer specifically to a 2012 article of mine on Naguib Mahfouz’s Miramar, a novel long considered to have foretold the June 1967 defeat on the eve of which it was published.

Miramar is set in a seen-better-days pension on the Alexandrian Corniche owned by Mariana–an elderly, conniving Greek woman clinging to her fading beauty–sometime in the early to mid-1960s, as the novel echoes with the quasi-socialist laws of summer and autumn 1961 which codified and extended “previous measures to nationalize the economy through sequestrations and the limiting of large holdings and private enterprises.”[15] When Zohra–a young peasant woman fleeing exploitation and patriarchal pressures in the countryside–looks up her acquaintance Mariana, she is offered work at the pension.

This novel is only one of a handful of 1960s texts that Mahfouz–a writer as inscribed in Cairo as James Joyce is in Dublin–set in Alexandria. What was behind the choice of Alexandria as locale? The way I read it,

Alexandria was chosen as the setting of Miramar precisely to draw out a site-specific social reality as part of the novel’s broader political criticism. Consider the number of restaurants and enterprises that carry European names, having been established and owned by Alexandrians of European or mixed origins… [I do] not to make the claim that they are there in the text merely to lend local color or make for verisimilitude. I would contend that they reinforce Miramar’s chronotope of “random encounters” in spaces permeated with historical associations, and in so doing lend further credence to what I see as the reason why the novel was set in Alexandria, namely on account of the city’s providing an acute symptom of the quasi-socialist economic policies adopted by the Nasser regime, which comprised nationalizations and sequestrations of large assets and enterprises, particularly ones belonging to foreign-nationals. The text would seem to be targeting, if nothing else, the excesses in the execution of these policies. An atmosphere of panic obtains among Alexandrians of European descent as property changes hands between them and Egyptians.

If Mariana is a latter-day Justine-like Cleopatra, per the European troping of Alexandria as a woman, Zohra, whose name denotes “blossom,” draws specifically on an Egyptian tradition of representing Egypt as a peasant woman. Through Zohra and the crushing of her hopes by one of the four narrators who would seem to be exemplary of the New Man of the 1952 Revolution, therefore, the novel

lay[s] bare the emptiness of the revolution’s promise of greater social justice and amelioration of the subaltern’s condition. If it was the peasant and the worker who, in quasi-socialist fashion were cast as the primary addressees and beneficiaries of the revolution, certain undeniable rights having been secured for them, this orientation did not prevent the silencing of the subaltern masses nor the revolutionary leaders from arrogating power and privilege to themselves… The change of regime has not effected an egalitarian leveling of class difference; it has replaced the old elite by a new one at the helm. [16]

Nor was Mahfouz the only Egyptian writer to riposte to the Western troping of Alexandria as a woman.

The Alexandrian novelist, critic and translator Edwar al-Kharrat (1926-2015) provides a powerfully compelling contrast to Durrell. It is not that cosmopolitanism is absent from al-Kharrat–he does use the Arabic loanword for it, kuzmupulitiyya–and I have analyzed elsewhere (in 2004) the resonance in his texts of the dominant discourse on cosmopolitan Alexandria.[17] But “my claim is that the cosmopolitanism at stake is often imbued with, and not infrequently subsumed by, the revolutionary compatibility between nationalism and internationalism.”[18] I wrote this in a 2017 article that, amid a resurgence in interest in a Cairo-based 1940s and ’50s Egyptian Surrealism in recent years, set itself the task to address, among others, the overlooked avant-gardism in al-Kharrat and his Alexandrian contemporaries, only a generation younger than the Cairene group. While the fact that al-Kharrat had been involved in the radicalism of the 1940s is well known, there is hardly any criticism on his Trotskyism or, relatedly, the dialogue with Surrealism that resonates within his texts.

Al-Kharrat’s most explicit fictional document on his years as a militant is his monumental 2002 autobiographical novel Tariq al-Nisr (The Way of an Eagle), which depicts the Alexandrian counterpart to the far more frequently narrated Cairene uprising against the British in 1946. The narrator chronicles the activities of the Trotskyist group to which he belongs in the mid-’40s, his detention for two years at the end of that decade (like al-Kharrat himself), and his release–with flash-forwards to more recent history. To frame the Trotskyist, if somewhat eclectic, ideological orientation of the narrator’s group I had cited Leon Trotsky’s Permanent Revolution:

the completion of the socialist revolution within national limits is unthinkable… The socialist revolution begins in the national arena, it unfolds in the international arena, and is completed in the world arena. Thus, the socialist revolution becomes a permanent revolution in a newer and broader sense of the word; it attains completion only in the final victory of the new society on our planet… Different countries will go through this process at different tempos.[19]

Parenthetically: who are the unnamed parties Hawas alludes to when she claims that “misuses of terms like ‘nationalism’ and ‘internationalism’ interweave the pigeon-holing of inhabitants according to a ‘nationality’” (“HNWCA”)? My own work on al-Kharrat, in addition to providing definitional frameworks, has argued for the rich complexity with which he approaches nationality and ethnicity, as below.

Much to my delight, I was able to obtain copies of previously unpublished letters that al-Kharrat had sent out in his militant days and that matched up closely to his account in Tariq al-Nisr:

We have exchanged communications, for a long period, with the RCP in London and with our section in Palestine, with the International Secretariat…. we are in great need of party literature, for the purpose of translating the outstanding works of Trotsky and the movement into Arabic and educating our cadres and workers.[20]

The letter is signed “Edward Kolta,” Kolta being part of al-Kharrat’s full name. Surrealism–promoted by the Trotskyists–which al-Kharrat’s criticism has extensively addressed, echoes in his texts in passages “where the boundaries between dream and reality are blurred… where something in the order of stream-of-consciousness automatic writing unfolds, or where traditional generic codes, in particular the distinction between poetry and fiction, are undermined.”[21]

Foregrounded in al-Kharrat’s Alexandrian fictional texts are the city’s southern quarters, lower middle-class and working-class neighborhoods where ethnic variety is articulated differently. The texts’ painstaking subtilizing of class, in relation to ethnicity, and gender; hence the fictional texts’ nuancing “of the association between that key constituency of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism, those of foreign descent, specifically Greeks, and colonial complicity.”[22]

To demonstrate, let me turn to the half-Greek Sylvana in al-Kharrat’s 1990 novel Ya Banat Iskindiriyya (Girls of Alexandria). A friend, George, introduces the narrator to Sylvana at a skating-rink frequented by different ethnicities that also serves as a prostitution pick-up place, not least by Allied soldiers during World War II. George, much to the narrator’s disapproval, has designs on her: “‘The girl stays at home alone with her mother, an old hag, the Armenian bitch. Her dad’s Greek, and he’s in prison. Remember the story of the mutiny on the Greek ships?’… He said, ‘The girl’s toothsome, I tell you–still green and got her cherry.’”[23]

In the figure of Sylvana the discourse of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism collides with internationalism. Let me draw out of the reference to “the mutiny on the Greek ships” a “whole historical nexus of British imperialism, communist resistance thereto, and an Egyptian-Greek solidarity.”[24] The mutiny of the Greek navy in the Middle East, which was serving the allied cause, was predominantly communist and centered in Alexandria in 1944. It was ultimately crushed by Britain, though the siege of Greek ships, and cutting off of supplies to them, lasted longer than expected partly on account of the support offered by Egyptians, not least communists.[25]

Elsewhere in the novel, we come on the following surrealistic passage, which is worth quoting in full:

Near the huge oil storage tanks with their sparkling, ever-flickering flame, I saw a row of tough Afrikaner soldiers on the shore with their backs to us, looking out to sea, their weapons tensely raised while the huge white British frigate stood motionless on the sea, its cannons pointed at the small battleship with Greek letters on it, a red flag fluttering from afar on its mast–as though in a final, desperate gesture of defiance–and I saw a row of soldiers in helmets and bullet-proof glass visors, heavily armed, blocking the narrow streets once paced by prophets, poets, and dreamers, in Jerusalem, Ramallah, Nazareth, Bethlehem and al-Khalil, shooting children with machine-guns and hurling tear-gas grenades at them; soldiers surrounding the circular granite memorial that gleams by night in Tahrir Square and beating boys and girls with their batons; soldiers escorting prisoners to the closed, suffocating train carriages and the filthy, cold trenches in Warsaw and Siberia and the gas-chambers of Dachau; chasing the workers of the textile factories in Maḥalla and Kafr al-Dawwar and Karmuz and pursuing the students from Law, Medicine and other faculties on the ʿAbbasiyya hill [in Alexandria]. Their yellow tanks know full well their business and their long old-fashioned rifles open fire, so that hundreds drop in the spacious square in front of the Winter Palace; the sirens of the black cars howling in front of the Sorbonne; soldiers dragging by the leather leash trained, ferocious dogs to gnaw the legs of Blacks in Johannesburg and Mississippi alike. I was to find out, years later, that the British had executed hundreds of the rebel Greek sailors who had joined the liberation army in Greece, and that they had imprisoned the rest, until the revolution was smashed, after the war.[26]

The passage apparently free-associates, sparked off by the 1944 mutiny of the Greek sailors in Egypt, the narrative training our attention on a whole range of examples of state oppression, racism and authoritarianism from around the world, and revolt against them with only two sentence breaks. The reader is prompted to compare and draw connections between instances “vastly dispersed in time and space” before returning to the Greek mutiny.[27]

Sylvana might appear to be inscribed in a ready discourse of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism: the Hellenic inflection given her, and the fact that the narrator meets an older version of herself as a courtesan at a nightclub and sleeps with her. But such a reading is variously subverted. The narrator’s later encounter with her is indicative of how the colonized man, no matter how disenfranchised, can be, in particular situations, more enfranchised than a woman of European origin in the Alexandria of the period. The text points us to the way her commodification has been effected at the nexus of class and doubly-determined patriarchy, reinforced in this case by the additional layer of British imperialism. Sylvana stands for that facet of the Greek presence in Egypt with which the Kharratian text identifies–internationalist solidarity. In this sense, where the text associates Sylvana with Cleopatra, it intertextually nods towards Durrell’s “princess and whore” and also subverts the association by mapping in the historical and material conditions that produce her commodification.

Alexandrian civil movements, and the built and natural environment

We are long past the stage of amazement about how the movement of protest that swept the Arab world in 2011, and radiated outwards from there, came about. One insight, at least, to be gleaned has to do with the unregistered micro levels on which social movements operate. Apart from well-known causes, many were the preludes to the Egyptian Revolution of 2011: Tunisia sparked it off, and, in a local context, the Cairo-based Kifaya (or, the Egyptian Movement for Change), which fought against the extension of Mubarak’s rule and the scenario of his bequeathing the presidency to his son, is rightly credited with a role. In the Alexandrian context, a prelude often pinpointed is the murder of Khaled Said, who had collected evidence of police wrongdoing; the rest–protests on the Alexandria Corniche, the Facebook page “We are All Khaled Said”–is history. I make these points not to retroactively produce a teleological account, leading to the Revolution, or to myopically reduce a movement of protest of such scope to an Alexandrian ambit but rather to suggest that the Revolution’s placing center-stage of Egyptian civil and social movements ought not to blind us to the long-term, incremental, invisible ways, beyond the illustrious instances in the build-up cited above, in which civil society is reinforced. One should have thought, indeed, all this would be obvious.

Opines Hawas, “Seventy years of Egyptian sovereignty later: which camp speaks for Alexandria’s ruined infrastructure? Who can defend the death knell given to the city by Nasser and sustained by subsequent governments? Who speaks for the current Alexandrian cesspit, this polluted, over-populated and corrupt city of waste?” She even claims that, “we have no one to blame but ourselves –but academia isn’t really going there.” And she closes her article apocalyptically with: “our history is continuously destroyed by the climate, both environmental and political. And no academic discourse about cosmopolitan Alexandria has emerged to express the terrifying inevitability of this quotidian” (“HNWCA,” emphasis added).

The statement, in my view, bears no relation to the signal efforts of members of Alexandrian civil society who saw no “inevitability,” let alone a terrifying one, in the degradation of the urban and natural environment, as well as the attrition of heritage. A caveat: I will not be snared into overstating the case in riposte. That said, Alexandrian academics (not everyone, by any means–but where else are all academics involved in such issues?), and the city’s civil society (again, not everyone–ditto), should not be made to believe that “we have no one to blame but ourselves.” (Hawas is free to blame herself, if she so wishes: I will not probe.) Several key players did “speak” up, took firm stands and–often with limited resources, financial and otherwise, as well as the knowledge that position-taking involves the risk of repercussions–invested a great deal of effort into resisting the degradation.

The blanket statement representing Alexandrians as the guilty party in the current state of affairs not only flies in the face of certain facts of the matter but also potentially plays into the degradation by propagating what I view as a spurious narrative of wholesale acquiescence. Instead, a responsible attitude would be to support and applaud local struggles for safeguarding the natural and built environment, that is if we are to hope to bequeath a more livable urban environment to posterity. Documenting these struggles, furthermore, gives future activists a genealogy that empowers them, previous experiences on which to draw, precedents (successful or not) in the name of which to work to secure rights–it being understood, too, that they are entitled to define themselves against precedents, as long they do so in an informed and intelligent manner, and with integrity, also so that the rug would not be pulled from under their feet.

Indeed, the current degradation of the urban environment is the outcome of the conjoined forces of economic liberalization (including the Open Door policy, privatization and the lifting of sequestrations) and corruption. If anything, the sequestrations of villas and mansions under Nasser (which then, for the most part, came to serve a variety of government functions) had the indirect effect of pickling, as it were, that architectural heritage–preserving it, if without much maintenance. Hawas appears to be oblivious to the fact that under Sadat sequestrations were lifted and property was eventually returned to the owners, many of them foreign nationals. A lot of the owners then promptly sold: it was then that the demolitions began, and have continued ever since. Given that nation-wide laws protecting the architectural heritage exist, even at one point (1990s) additional Alexandria-specific decrees, the lifting of sequestrations need not, in theory, have had a detrimental impact on that heritage. The regular flouting of legality is the outcome of corruption–a corruption aided and abetted by, since built into the economic sea-change, and one long fought by members of Alexandrian civil initiatives, academics included.

Archaeological excavations have a long history in Alexandria. But, for the purposes of this discussion of the post-1952 period, it should be noted that while land excavations were well served in the 1960s by the Egyptian Antiquities Department, as well as a Polish mission that undertook very important work, what was off-limits was the sunken vestiges, partly for security reasons. When in the 1990s underwater archaeology was very much in the cards, I researched an amateur underwater diver, Kamel Abul-Saadat (1933-1984), who scrupulously and single-handedly for the most part, and at his own expense, investigated several submerged sites, including to the east and west of the city. His “endeavour is all the more significant for having taken place at a time when the authorities had neither the equipment, the expertise nor even the interest to deal with underwater archeology.” It should be recalled that the national agenda in the 1960s “privileged military spending and industrialization,” giving archaeological priority to the salvage of the antiquities of Upper Egypt prior to the construction of the High Dam. With good relations with the navy which often sought his help, Abul-Saadat was given access to the sunken sites, and thanks to his initial mapping of them and his campaigning, some antiquities were lifted from the bottom of the sea in 1962. Abul-Saadat was to join forces with a professor of oceanography at Alexandria University, Selim Morcos, author of the 1965 volume Hadarat Ghariqa (Sunken Civilizations): the oceanographer “was to act as a sort of academic mentor,” instructing the diver “to adopt more professional practices, and record his sightings and sketch objects seen underwater.” It was thanks to that collaboration, too, that Morcos, with international contacts, made the case with key figures in underwater archeology abroad that eventually resulted in UNESCO sponsoring, in collaboration with the Egyptian authorities, a mission by the pioneer underwater archaeologist Honor Frost and the geologist Vladimir Nesteroff. Given that it was not before 1994 that a French-Egyptian team excavated the Pharos site, the previous work done by Frost, with the help of Abul-Saadat, was “to prove of great value for” them, “helping them determine the changes in the morphology of the site and to locate missing statuary and masonry.”[28]

Stirrings of scientific work on environmental pollution in Alexandria can be traced back to at least 1973, but “the beginning of systematic research on marine pollution in the city is the Project for Aquatic Environmental Pollution in Alexandria [1980-1986] whose National Director and Principal Investigator was Dr. Youssef Halim,” professor of Marine Biology, Alexandria University (full disclosure: the present writer’s father), according to a colleague and member of that project, Hassan Awad, Professor of Oceanography.[29] This Alexandria University-based project, co-sponsored by the Egyptian government and UNESCO/UNDP, which covered not only Alexandria’s coastal zone but also the areas east and west of the city, analyzed and monitored pollution from several sources, including sewage and domestic waste-water effluents, and industrial and agro-chemical waste.

As befits a project of such scope, it was, and from early on, “an inter-Faculty and inter-disciplinary activity,” involving faculty members not only from the Oceanography Department of the Faculty of Science, but also from the Faculty of Agriculture, the Faculty of Engineering, the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, and the High Institute of Public Health and the Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries. The findings of the Project for Aquatic Environmental Pollution in Alexandria appeared in international peer-reviewed journals and presented at forums sponsored by FAO, UNEP and CIESM (The Mediterranean Science Commission). Several MSc and PhD theses written by “[j]unior scientists… trained in the project laboratories by national scientists and visiting consultants,” provided a formation for Alexandrian scientists who, in turn, trained later generations.[30] “Those who worked in that project remain active and are advising others. Research on pollution [in Alexandria] is vigorous, there is so much work being done, as any online search would establish,” says Awad.[31] Significantly, the project’s ambition went beyond producing scientific research for consumption within the academy: it included a legislation committee, with representation from the Faculty of Law, to produce a “comprehensive review of all international and regional agreements, conventions and protocols concerning marine pollution control… for submission to the national authorities.” But as the terminal report put it pointedly, “Much better communications need establishing between the Unit and the various Egyptian authorities which deal with aquatic pollution and environmental quality. Such authorities could benefit from giving the Unit’s findings greater weight in their considerations. Such improved communications could allow the national authorities to make more extensive future use of the Unit’s capabilities.”[32]

This context is necessary to comprehend the incremental accumulation of local intellectual initiative, expertise and knowledge leading up to a very important workshop on that took place in 1997. This was “The International Workshop on Submarine Archaeology & Coastal Management” (SARCOM), co-sponsored by Alexandria University, UNESCO and the Supreme Council of Antiquities. It should be recalled that Alexandria in that decade had been witnessing two parallel projects that variously recouped its Hellenistic heritage, cosmopolitan iconicity and all. On the one hand, there were the much-publicized underwater excavations on what is presumed to be the site of the Pharos Lighthouse (led by Jean-Yves Empereur) and of the Eastern Harbor (led by Franck Goddio), including the Ptolemaic Royal Harbor. On the other, there was the ongoing construction of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a moving spirit behind which was Mostafa El-Abbadi, professor of Classics at Alexandria University, sought to capitalize on the iconicity of the Hellenistic Ancient Library to secure for the city an up-to-date library.[33]

With international attention converging on the city, “SARCOM was a group proposal made by the Alexandrian oceanographers, Dr Youssef [Halim] and myself, with Dr Selim [Morcos] who served as our external dynamo as he [had moved to] UNESCO [as Senior Programme Specialist, Division of Marine Science],” recalls Awad. The main objective of the workshop, he elaborates, was “to propose means to mitigate the conflict of interests between stakeholders of the area of submerged archeological sites of Alexandria to ensure the sites’ conservation and sustainable development as a part of human heritage.”[34] However, the idea was also “to convene an international workshop bringing together the marine environment and archaeology. We appealed to the priority given to archaeology to protect the marine environment and promote work on the pollution problem,” particularly since the core team considered the establishment of an underwater museum with the antiquities left in situ.[35]

Later published under the title Underwater Archaeology and Coastal Management: Focus on Alexandria, the workshop brought together local and international historians, archaeologists, oceanographers, engineers, conservationists, Egyptian authorities, and investors. Taken in concert, the presentations connected the previous history of underwater archaeological work with the findings of the contemporary phase, in relation to other submerged sites around the Mediterranean, with interventions on pollution and its impacts on the Alexandrian marine environment, as well as state-of-the-art techniques of remote sensing and conservation of underwater artefacts, in addition to legal issues. Mechanisms for following up on the workshop’s recommendations were set up, and the “SARCOM Workshop’s potency was ultimately its effectiveness as the point of origin for a series of pilot projects and their inscription within UNESCO programmes.”[36]

An excellent monograph on the debates about heritage of that period is Beverley Butler’s Return to Alexandria: An Ethnography of Cultural Heritage Revivalism and Museum Memory (2007). Butler’s central case study is the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, as well as underwater archaeology and urban revivalism. Attending to the multiple and multivocal engagements of heritage by different “actors”—the intellectual elite, politicians, officialdom and also ordinary citizens—she produces a narrative of “radical transformation” of Alexandrian heritage “from an elite Western colonial paradigm into an operational model of heritage revivalism in a ‘postcolonial’ context thus confront[ing] [Western] museological/heritage theory with alternative sets of values, critical approaches, theorisations, lived experiences, and life-worlds that currently remain largely unrecognized.” In an interview with Butler,

[Youssef] Halim outlined the need to “twin revivalism with development” while subsequently articulating his “fear” that “this will place heritage and archaeological projects in the domain of private business” and that “urban revivalism could collapse at anytime if profit is prioritised over people.”[37]

The interview took place back in 1999, before the current collapse.

One important initiative in Alexandria has been the NGO Friends of the Environment Association (FEA), established in 1990. Led by the dynamic Dr. Adel Abu Zahra (1948-2003), FEA spread awareness of environmental issues and rights, and was responsible for a number of campaigns in the city. It was, back then, unusual to take the government to court on environmental grounds, as FEA did on more than one occasion. When the authorities were planning to replace old tramway sleepers with unfit ones, FEA joined an Alexandrian lawyer who initiated a lawsuit against the government on account of the noise pollution that this would cause. A much more widely publicized and landmark FEA lawsuit was against the government’s decision to cede to the WHO (then) offices in Alexandria a side-street leading to the Corniche: the success of the campaign served to make the point that it can be done, that environmental activism was not, as many thought at the time, a naive, utopian pursuit in Egypt under Mubarak. Abu Zahra himself had a media presence and platform, and the FEA regularly organized public lectures on the environment, which helped spread environmental rights awareness in the city and highlight site-specific issues such as marine pollution.

Discourse within another academic discipline, namely architecture, informing a sustained endeavor to preserve Alexandria’s built environment together with, indeed, an emphasis on its so-called cosmopolitan period has for decades now been produced by Mohamed Awad. A professor of architecture at Alexandria University and third-generation practicing architect, Awad has, since the early 1980s, conjoined research on the city’s built heritage, published in both scholarly forums and ones accessible to the general public, with preservation activism. In 1985, Awad founded the Alexandria Preservation Trust (APT) which has collected much archival material on the city’s architectural heritage–some of which eventually formed the nucleus of a permanent exhibition at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, double-billed “Impressions of Alexandria” and “Cosmopolitan Alexandria,” including engravings and, these being recent additions, models of monuments that no longer exist, such as the Pharos Lighthouse.[38] A central activity of the APT, as its website states, is “documenting and listing buildings of historical and architectural merit,” while Awad’s own conservationist activism has followed different strategies over time. In the mid- to late 1990s, he was associated with high profile campaigns, whether in tandem with FEA, of which he was a founding member, or singly sponsored by APT, as when he successfully secured a temporary halt of the construction of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina so that a salvage excavation could take place (mosaics unearthed at the time are now housed in the library’s Antiquities Museum). Starting the late 1990s, he turned to working with and through official channels, in particular Alexandria Governorate within which he chaired (2008-2018) the Permanent Committee for the Conservation of Alexandria–for the listing of buildings–and is currently chair of the Technical Committee for the Conservation of the City–for assessing and authorizing restoration projects.

At one stage, his proposal for an equestrian statue of Alexander the Great on the city’s oldest street met with a public controversy about cultural identity and cosmopolitanism in the city (see AC 271-272). The statue was unveiled during the Bibliotheca Alexandrina inauguration and, aware of the fact that both his grandmothers are Greek, I had written at the time that Awad was “performing devotions as much to a family lineage as to an intellectual genealogy” of Hellenistic cosmopolitanism. I do not always agree with Awad’s take on Alexandrian cosmopolitanism, which places an inordinate emphasis on things elite and European. That said, his scholarship is a reference on the European architecture of the city, as in the monograph published by APT, Italy in Alexandria: Influences on the Built Environment, the longest chapter of which is titled “Defining Cosmopolitanism: Pluralism in Eclectic Historicism.”[39]

The “Villa Ambron itself, in which Durrell lived,” Hawas states, “was torn down post-2011 (in spite of the few uncelebrated Alexandrians who bravely protested, as they have against other demolitions)” (“HNWCA,” emphasis added). She does not divulge who these Alexandrians are. I confess that, for years now, it has given me a secret satisfaction, whenever I read “Villa Ambron” in print, to know that the reference has gone into public discourse thanks to a series of articles that I myself published in the Al-Ahram Weekly over several years, starting in 1995. I set myself the task of writing these sometimes broadsheet page-length articles as part of a campaign that I–in collaboration and academics such as Mohamed Awad, the late Durrell scholar Soad Sobhi, and NGOs such as APT and FEA–launched to preserve that structure and adjoining ones on the Ambron property that were at the time threatened with demolition. It was all the research work I did in that series that, virtually for the first time, documented and made available the story of the Ambron family who had owned and eventually sold the property. The campaign then got picked up, from the pages of Al-Ahram Weekly, in both the local and the international media. It was thanks to the visibility of this sustained media campaign carried out by me in Al-Ahram Weekly, and efforts by the APT, the FEA, and the Center for Studies of Egyptian Civilization, that the Ambron villa survived from 1995, when demolition of another part of the property had begun, until roughly three years ago.

The Ambron property, in addition to the main mansion with a turret in which Durrell was a lodger during World War II, included a smaller structure, an atelier in the garden, in which the Egyptian artist Effat Nagui (1905-1994) lived for the last thirty years of her life. The garden contained a sundial, antique columns and capitals, and a huge banyan tree. After Nagui’s death, the Ambron heirs sold the property to a construction company. In the series of articles I wrote, I made the case for the preservation of the Ambron property not only by investigating the construction company’s dubious claims and interviewing officials from the local Alexandria Governorate district office, the Supreme Council of Antiquities and the Ministry of Tourism, but by refurbishing the property with its former cultural associations.

I tracked down, through interviews with Alexandrians such as de Zogheb and old records of the city’s elite, the history of the Jewish-Italian Ambrons: the father Aldo, a civil engineer, his wife Amelia, an artist for whom the atelier was built (I reproduced a portrait by her), and their daughter Gilda and son Emilio, both artists. As a literary scholar who had already written an MA thesis which treated Durrell, I adduced textual and biographical connections, as in: Durrell’s references to the mansion in his letters to Henry Miller; the name Gilda Ambron in one of the incantatory passages of the Quartet, her home likely to have inspired some of the social events depicted by Durrell; a passage on the encounter between the Alexandrian artist Clea Badaro, one of the sources for the Clea of the Quartet, written by her sister, together with a sketch by her of the British novelist that I published; interviewed Paul Gotch, Durrell’s roommate in the Alexandria years, and the novelist’s Alexandrian second wife, Eve Durrell, among others.

And I worked on imaginatively recreating the ambience of Effat Nagui’s home, publishing a picture of her at home coupled with a description of her house, by her friend Nawal Hassan, which contained not only a large collection of objets d’art and folkloric pieces she and her husband Saad al-Khadim, a pioneer of folklore studies, had gathered, but also “at another remove, the transmutation of folklore in her own paintings. The vocabulary of her work was drawn from the folkloric, the arcane and the magical,”[40] Nubia being a prominent theme. I cited the role that Effat and her brother, the prominent artist Mohamed Nagui, had played in the founding of the Atelier d’Alexandrie. I also cited the encounter between Durrell, back in Alexandria in 1977 for the BBC documentary Spirit of Place, and Nagui who invited him.[41]

The artefacts and elements of a museum that campaigners, myself included, pressed for were all there. On my part, it was in these terms that, in a 1995 article, I conceived of the Ambron property as patrimony:

The associations of the two houses certainly give unto the dual heritage of Alexandria, the Egyptian and the cosmopolitan: Effat’s own merging of modernist European culture with Egyptian, African folklore, and Durrell’s colossal Orientalist refashioning of the city, an exercise which bears the marks of his own ambivalence towards Alexandria, both as a city with its own specificity and as a metaphor for the Orient.[42]

I solicited a statement from the International Lawrence Durrell Society, from Durrell’s second wife, the Alexandrian Eve (to whom he dedicates Justine), and Gotch. It was when I informed Gotch in January 1998 of the threat of mansion’s demolition that he then made the case for its preservation to the Egyptian Ambassador in London during a Friends of the Alexandria Library meeting. When Gotch’s speech was relayed, via the Minister of Higher Education, to the governor of Alexandria, the latter solicited advice from Awad, who recommended that the ex-Ambron property “be expropriated for the general public.”[43] As I verified at the time with the authorities of the district under which the ex-Ambron property falls, they had been notified by the governor of Alexandria that no demolition permits be issued. (Anyone who has read Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism would know of my role in this campaign, as it is cited there on pp. 377-78, endnote 3. I should add that, in those years, I wrote on many subjects relating to the built and natural environment, including pollution, the environmentally unsound widening of the Corniche that encroached on the beaches and enabled their privatization, and other landmark buildings threatened with demolition, such as the former home of ‘Abdullah al-Nadim, nationalist writer and orator of the 1882 ‘Urabi uprising, and–in both English and Arabic–the grand old San Stefano Casino and Hotel before and after it was torn down.[44])

The next stage in the fate of the ex-Ambron property is worth highlighting on account of a new group of preservationist who emerged in Alexandria. When, a few years ago, the construction company launched and won a lawsuit against the authorities, removing the structures from the list of buildings to be preserved, the Effat Nagui atelier was the first to go–now replaced by a multistory housing block. Save Alex, established in 2012 by a group of young Alexandrian architects, campaigned for the preservation of Alexandria’s architecture, including the Ambon property, but also expanded their purview from “built heritage to built environment, since there is an environmental decay in Alexandria,” although priority was given to the built environment since this is the most urgent issue. Discussing the long history of the campaign with (then) members of the Save Alex team, the architects requested copies of my articles on the ex-Ambron property, which I made available for the sake of their documentation and continuity of efforts.[45]

The Agency of Cultural Projects: Approaches to Heritage and Contemporaneity

The closing pages of Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism were entitled “Epilogue/Prologue.” As part of the epilogue, I considered the legacy of the dominant narrative about the city’s cosmopolitanism and the afterlife of the triumvirate’s texts–in memoirs of diasporic Alexandrians of mixed origins, in Arabic translations of the canonical texts, Egyptian cinematic adaptations and even an Egyptian postmodern novel centering on Cavafy. The thrust of the prologue was an anticipation of my next project on Egyptian literature about the city and a range of recent Alexandrian cultural initiatives.

In the “Epilogue/Prologue,” I had written that,

The dominant narrative of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism critiqued in this study has been polyphonically modulated in recent decades… Egyptian writers and artists have engaged this legacy in diverse and sometimes contrasting ways. (AC 273; emphasis added)

The research I have been doing for that second project, which I draw on here, has only corroborated my sense of the diversity of the Egyptian Alexandrian creative dialogue with the city’s heritage, writ large, and its imaginaire of heterogeneity. I do not claim to give an exhaustive, critical account that covers all of the Alexandrian cultural initiatives of the past 15-20 years, as space does not allow it. Nor can any diachronic mapping of a given project be offered here–Egyptian temporality, with all its breathtaking leaps, somersaults, and defaults turning on a utopian/dystopian fulcrum this past decade, deserves a study unto itself. Likewise left out of the commentary on different cultural projects here are the genuine collegiality, the tactical collaborations and both the sharing of or vying for space, resources, funding and “distinction” (there’s no town like Alex, but Alex is a small town); the discussions I have had with some players about what constitutes “independence” in the cultural field and the shifting ways in which independence is sometimes defined in relation to, or against, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, this institution being at times figured as a metonymy of establishment, state-sponsored culture, even by cultural producers who have been involved in the BA; the extent of outreach/audience, this also in relation to medium (e.g.: visual, musical or literary; the intermediality, too, would be worth exploring elsewhere) and sub-genres.

Alexandria and its heritage have become what Pierre Bourdieu calls “cultural capital.” But what this consists of has been construed in rather different keys.[46] Let me identify a few. From the 1990s until the present period, Alexandria has witnessed the publication of several cultural magazines, in some cases financed by the editors, such as the benchmark Amkenah (Places), published by the photographer Salwa Rashad and her husband the writer and poet Alaa Khaled starting 1999 (their publication was preceded by such local literary magazines as al-Arbi‘a’iyyun, meaning the Wednesday group). Amkenah’s distinctive feature is ethnographies of place, “privileging ‘story’ over ‘history,’” collecting oral narratives about a diversity of sites–in Alexandria, but also the countryside and the desert.[47] This is complemented by a wide variety of accounts of Alexandria’s culture–profiles of a given older Alexandrian the writer knew, a narrative of a relationship with a particular quarter, “myths of everyday life,” as one of the dossiers had it. There is no set editorial line dictating how (or even any imperative) to deal with “cosmopolitanism,” although essays on the subject from a range of perspectives are included. And then there was the short-lived experiment Meena: A Bilingual Journal of Arts and Letters, published collaboratively by writers from Alexandria and New Orleans–“meena” means harbor–adventurously setting these two cities in dialogue. On the Alexandrian side, it was an outgrowth of previous publications, collectives such as Khamaseen and al-Kull. When Meena ceased publication, it was later replaced by the local Alexandrian Tara al-Bahr (“With a Seaview,” a phrase lifted from the lingo of real estate agents), edited by the Alexandrian poet and translator Abdel-Rehim Youssef. This, too, is eclectic in its coverage of Alexandria, not unlike Amkenah. (Full disclosure: the present author has published articles in Amkenah and Tara al-Bahr, and a literary translation in Meena.)

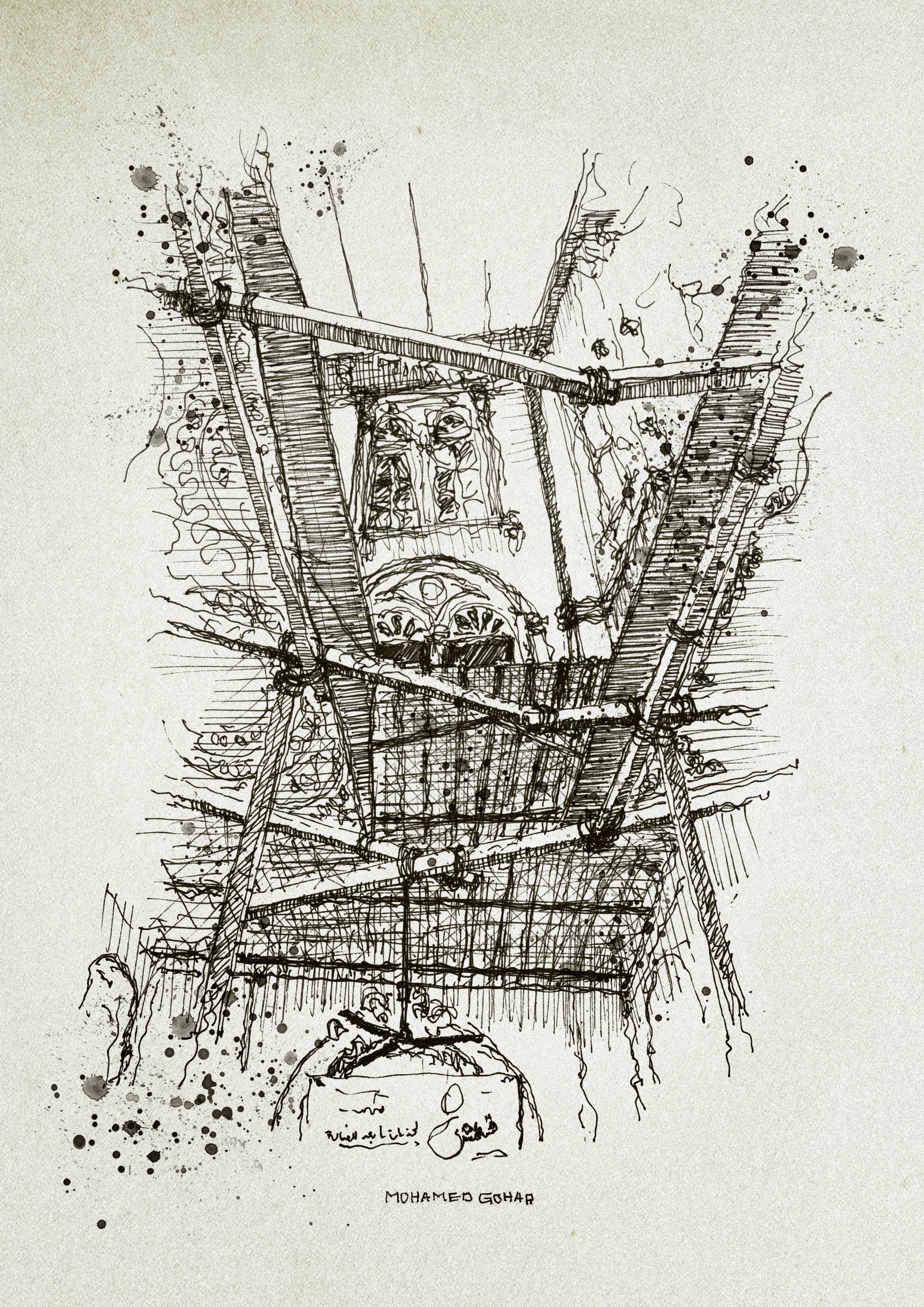

If Save Alex has sought to preserve the built environment, Mohamed Gohar, an architect, has adopted a different approach: his Description of Alexandria, a wink at Napoleon’s Description de l’Égypte, is a project of painstakingly documenting through sketches and a series of cross-sections of research on a given building, the city’s architectural heritage. The aim is “to enhance the engagement of society in preserving” its “legacy through long-term awareness,” as the project’s website states. How does Gohar explain his choice of sketching over photography or filming of buildings, particularly given the threat of architectural demolition? Aside from its being the tool of his profession, he explains, sketching (he uses ink) allows for more painstaking architectural line detailing, and the accumulation of textual material and notes around the drawing, without being overly time-consuming; and, to his mind, it affords an aesthetic quality, even when depicting a ruin, that surpasses other media’s. One of his references was Forster’s Alexandria: a History and a Guide: although he finds the author “Orientalist and the description incomplete,” it gave him an “image” of the early twentieth century city that he has supplemented from other sources. For a while, Gohar was joined by volunteer sketchers on Fridays, mostly male and female architects, my meeting with them having been hosted by Abdullah Sharkas, filmmaker and director of Janaklees for Visual Arts. The walks followed a plan that began from the oldest part, the West of the city. Before the walks, documentation on buildings in the sketching lane would be researched, and during the process, oral narratives about the place, by the inhabitants of the building and neighborhood, would be grafted in. It is a holistic approach, as in the notion that the loss of a building involves the loss of a bigger “value”: “it is the loss of the personalities who lived there, it impacts the architect, the old man who lives in the building, the owner of the shop downstairs.” The activity raises awareness of the architectural value of even dilapidated buildings, children being the constituencies most drawn to the sketching proceedings. The sketches have been exhibited and the first volume was published at Gohar’s expense.[48]

A relevant point here is the sometimes precarious new lease on life that different cultural venues have given to spaces long closed, half demolished, or at risk of being eventually demolished. One project that holds much potential in this regard is Wekalet Behna, a cultural center until recently run by the (now dissolved) NGO Gudran for Art and Development.[49] Officially inaugurated in March 2014, the center is in the offices of a film company, Behna, the name of which generations know from the credits of cinematic classics produced from the 1920s to the 1960s. The Behna family–Syriacs from Mosul–fled Kurdish persecution in the late 19th century to Aleppo, according to their Alexandrian descendant, Basile Behna. From there, his grandfather relocated the family, including four sons, to Alexandria at the beginning of the twentieth century. After trading in cotton, silk and tobacco, the four brothers eventually established their film company, starting with importation in the late 1920s, and then, from the early 1930s, launching into various aspects of the local industry–production, later sub-contracted executive producing, and distribution. When Behna Film Selections Company was sequestrated under Nasser in 1961 (a film was made by the sequestrator under the Behna name in the mid-’60s), Behna and his family moved to Lebanon, his mother’s country of origin, in 1964.[50] In 1974, with the lifting of sequestrations under Sadat, Behna embarked on what turned to be an almost forty-year legal battle to reclaim the company and its assets. And when the lawsuit was won, the 600-square meter apartment–another pickled space–located in a beautiful old building off Manshiyya Square, the Okelle Monferrato which has a (once glass-)domed inner courtyard, was opened. It yielded a cache of cinematic archival material: film reels, posters, photographs, correspondence, etc. The offices had a strong “scribal” infrastructure, Behna explains, and not only are contracts with stars and production budget paperwork preserved, but even the smallest receipt for a rural troupe’s projection of films on bedsheets.

A sketch by architect Mohamed Gohar of Okelle Monferrato’s domed inner courtyard, which contains ‘Ali al-Hindi Café frequented by Alexandria’s artistic bohemia. The building also houses the offices of Behna Film Selections Company, responsible for the production of many Egyptian cinematic classics from the 1930s until 1961, reopened in 2014 as a cultural center. The sketch is part of Gohar’s Description of Alexandria, a project that documents and raises awareness about the city’s architectural heritage. Image courtesy of the artist.

In view of this family heritage coupled with the history of sequestration and the legal battle, how does Behna view the elite Europeanized/Levantine francophone Alexandrian cosmopolitanism of the first half of the twentieth century? “The product of a flawed dream gone sour and sprinkled with a few mothballs,” he puts it pithily. How and why he perceives it as such relate to his class, ethnolinguistic and ideological position. He and his father Edouard grew up in the middle middle-class Sporting neighborhood of the city. Although Edouard was Shami (Syro-Lebanese), “he was not like them [Europeanized-Levantine]; he was Egyptian Alexandrian, and did not have this khawagati [resident local European/ized] style. The Arab bit was there in him and his friends, people like [director] Togo Mizrahi… they never played that part which others lament now.” (This is a formation, incidentally, quite reminiscent of the younger Youssef Chahine’s in Alexandria.) The father would greet acquaintances with affectionate swearing in Egyptian colloquial Arabic, thrust his hand into his pocket and distribute cinema tickets. True, “there were class differences in the neighborhood, but it did not have a khawagati style.” While the Behna brothers were motivated by commercial gain and not political or ideological awareness, he suggests, the company, particularly through its distribution activity, effectively contributed to spreading Egyptian colloquial Arabic in the Arab world, making it a common dialect understood by all in the region, including those who do not read Modern Standard Arabic. And what ideological position does Basile’s own self-reflexivity emerge from? These reflections, he suggests, are inflected by his own “militant” experience in the Lebanese left during the Civil War, “when decision-making” had major political ramifications.

Hawas, for her part, prefers to see things in rather unproductive since rather reductive, if eye-catching, binaries:

Academic scholarship on cosmopolitan Alexandria in the past two decades has famously divided into two camps. These might be called the “nostalgic cosmopolitanists” and the “anti-nostalgic cosmopolitanists.” (“HNWCA”)

She appears to have come across some viable cultural production, but her account, to my mind, actually skews the picture:

This is where the work of the nostalgic cosmopolitanists has actually been effective. Acting on the impetus to reclaim a hold on the shores of the Mediterranean, the past decade has witnessed a generating of paper histories, coffee table books, memoirs, and maps –piecemeal archives, all drowning in nostalgia. These are supplemented with documentaries in which the remaining handfuls of Greek-Egyptians, Italian-Egyptians, or Shawam-Egyptians all insist: we are here, we exist. All this has undoubtedly helped raise the generations of scholars on Alexandria who are even now rebelling against romanticised representations of the city. (“HNWCA,” emphasis added)

The endnote she provides here refers to the publications of Bibliotheca Alexandrina’s Alexandria & Mediterranean Research Center (Alex Med) and the digitalization of much archival material by the Centre d’Études Alexandrines (CEAlex). The cause and effect account does not hold water. Projects such as Amkenah, for example–multivocal, not rebelling–predate the printed matter (Alex Med) and digitalization project (if not CEAlex as such) she refers to, and several Alexandrian cultural initiatives are unindebted to either forum.

Furthermore, no references are given to any documentaries. Did they project fully-formed, much as Athena sprang out of Zeus’ head? And what might it indicate that there are several of them?